She’s not struggling because she’s a woman or because of her race—it’s the collision of both. Here’s how conscious leaders are seeing what they’ve been missing.

The Moment You Stopped Seeing

You’re in a meeting. Three people present ideas. One is a Black woman. Her idea is innovative, well-researched, backed by data. But you notice something subtle: When she speaks, people interrupt more. When a white male colleague presents a similar concept moments later, the room leans in.

Later, in the hallway, a colleague comments: “She’s so assertive.” Same word they used for the white man? Ambitious. When she’s assertive, it sounds aggressive. When he is, it’s leadership.

You didn’t intentionally miss this. But you’re seeing through a lens that doesn’t account for the intersection where gender and race collide.

This is gendered racism. Not as a single bias, but as a compounding invisibility—the unique discrimination faced by women of color when sexism and racism converge.

Understanding Gendered Racism: The Intersection Where Invisibility Lives

Gendered racism isn’t just sexism plus racism. It’s a distinct phenomenon where the two systems of oppression interlock, creating unique barriers that neither gender nor race alone explains.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term “intersectionality,” demonstrated this clearly: A Black woman faces discrimination that a white woman doesn’t face. And discrimination that a Black man doesn’t face. The combination creates its own unique shape.

Think of it this way:

A white woman in leadership might face sexism: “You’re too emotional to lead.”

A Black man in leadership might face racism: “You’re not a cultural fit.”

A Black woman in leadership faces gendered racism: “You’re too aggressive” (coded language pulling from both sexism—women shouldn’t be assertive—and racism—Black women are threatening). “You don’t fit the role” (she’s simultaneously not feminine enough and not masculine enough, depending on what the observer needs to see).

It’s not additive. It’s exponential.

Research from the Catalyst Institute (2022) found that women of color in corporate leadership faced 1.5x more microaggressions than white women and 1.7x more than men of color. They weren’t being discriminated against for being women, exactly. They were being discriminated against for being women who are not white.

This distinction matters because it’s invisible in typical diversity initiatives that address gender and race separately.

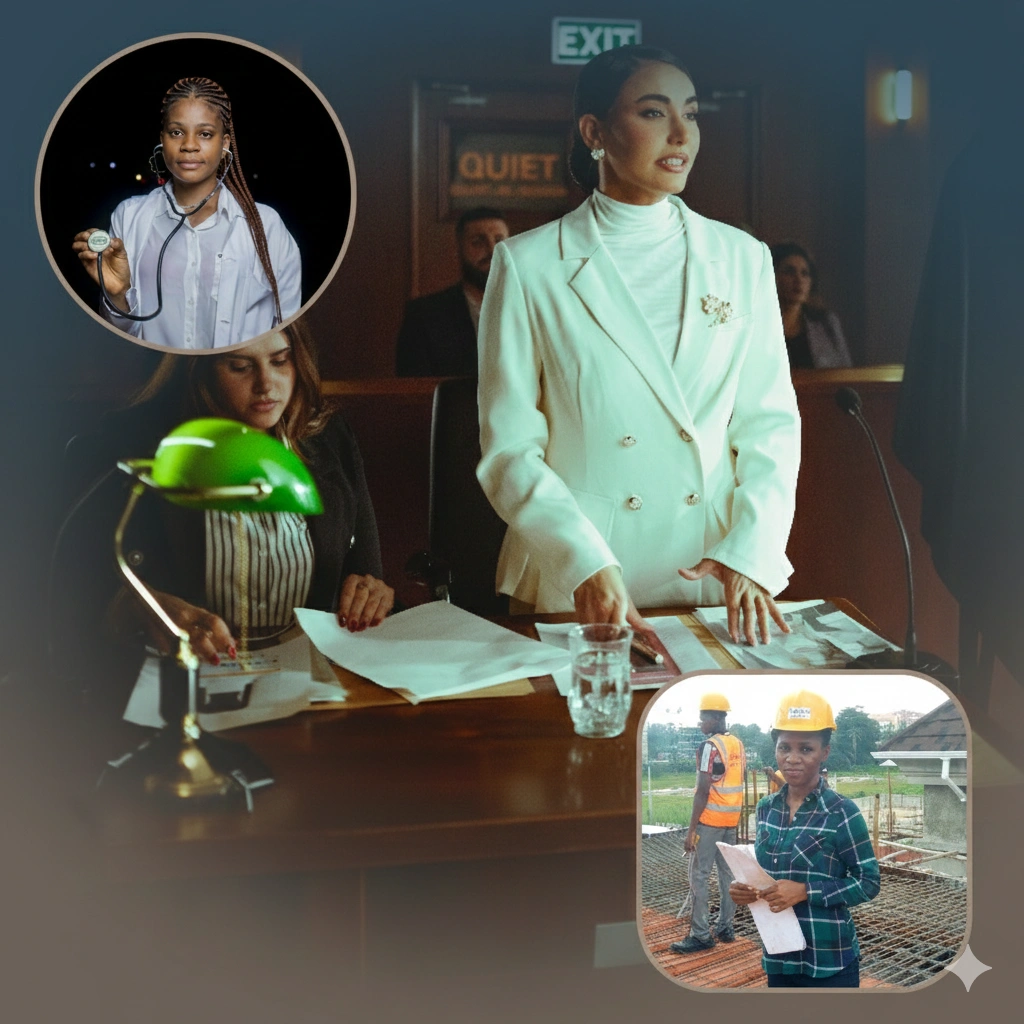

Where Gendered Racism Crystallizes: Real-World Examples Across Professions

Law: The Partner Track That Doesn’t Exist

In prestigious law firms, the partner track is well-documented for being male. But data shows a more complex picture: The track is also racialized.

A Harvard Law School study (2023) tracked promotion patterns over a decade at major firms. Their findings:

- White women: 34% made partner

- Men of color: 28% made partner

- Women of color: 11% made partner

The disparity between white women and women of color wasn’t about gender alone. It was gendered racism.

Why? In interviews with partners, several patterns emerged:

Women of color were asked about their “fit” with client comfort in ways white women weren’t. When Black female attorneys spoke assertively in court, partners noted concerns about “temperament.” When white female attorneys did the same, it was noted as “confidence.”

One Black female attorney described her partner review: “I was told I was too aggressive with opposing counsel. When I asked for examples, they said ‘the tone.’ When I asked what tone, they couldn’t specify. But I knew what they meant. A Black woman standing firm is aggressive. A white man doing the same is skilled.”

She left the firm. So did 60% of women of color at that firm within five years, compared to 28% of white women.

Medicine: The Double Bind That Silences

In hospitals, women of color physicians face a specific form of gendered racism: the expectation to be both highly competent and non-threatening.

A Johns Hopkins study (2023) found that female physicians of color reported:

- 58% higher rates of being mistaken for nursing or custodial staff by patients

- 47% higher rates of having their diagnoses questioned by patients and colleagues

- 34% lower rates of being chosen for mentoring relationships

But here’s where it gets interesting: When these physicians adopted more assertive communication styles (to command respect), complaints about their “bedside manner” increased. When they maintained warmer, more relational approaches, their medical competence was questioned.

It’s not a win-able situation. It’s a double bind specific to gendered racism: Be warm and lose credibility. Be competent and lose likability.

One South Asian female cardiologist documented her experience: “Patients assumed I was a resident, not the physician. When I corrected them assertively, I was ‘rude.’ When I corrected them gently, they doubted my expertise. My white male colleagues with the same credentials never faced this.”

She eventually left clinical practice.

Technology: The Visibility Paradox

In tech, women of color face a unique form of gendered racism: hypervisibility without recognition.

When a woman of color contributes an idea in a meeting, it’s noticed. She stands out. But the idea often gets attributed to someone else—usually a white man—or gets praised for different reasons.

A Stanford study (2023) analyzed 1,200 tech meetings. They tracked contributions and attribution. Results:

- Ideas from women of color were interrupted 23% more than others

- When a woman of color’s idea was praised, it was often for different qualities than intended (creativity instead of strategic thinking, for example)

- Follow-up credit for developing those ideas went elsewhere 41% of the time

One Indian female engineer described it: “I suggested a technical architecture. My white male manager called it creative. A white male colleague suggested something similar later, and it was called innovative. Same idea. Different adjectives that implied I was thinking outside the box emotionally while he was thinking strategically.”

She was eventually sidelined from technical leadership, placed in “diversity and inclusion” work instead—a well-documented pattern where women of color’s contributions are redirected toward DEI labor rather than their core expertise.

Finance: The Credibility Gap That Compounds

In investment banking and asset management, women of color face compounded skepticism about their competence and authority.

A Morgan Stanley study (2022) tracked client interactions with junior bankers. When a white male junior banker presented to a client, clients asked substantive questions about the investment thesis. When a woman of color presented the same thesis, clients asked about her credentials and background—essentially questioning whether she belonged in the room.

One Black female investment banker shared: “After I closed a major deal, the client asked my white male colleague, ‘How did you put this together?’ They assumed he was the architect even though I’d led it. When I clarified my role, they seemed surprised. Then they asked if my firm had ‘stretched’ to include me.”

She wasn’t struggling because she was a woman. She wasn’t struggling because she was Black. She was struggling at the intersection—where both biases conspired to render her invisible or implausible.

The Systemic Cost: How Gendered Racism Depletes Organizations and Nations

You might think gendered racism just affects individuals. But it costs organizations billions.

When women of color leave fields at higher rates than white women and men of color, organizations lose diverse talent at a critical point—right when they could influence culture and decision-making from leadership positions.

A Boston Consulting Group study (2023) tracked attrition patterns. Women of color left organizations at 1.8x the rate of white employees over five years. The cost:

- Lost institutional knowledge

- Reduced diversity in decision-making

- Weaker mentorship networks for the next generation

- Diminished innovation (diverse teams innovate faster, but only when diverse voices aren’t being silenced)

At the national level, this compounds. When women of color—who represent 25% of the US population—are systematically excluded from leadership, governance, and innovation, the nation loses 25% of its potential problem-solving capability.

Research from the National Bureau of Economic Research (2023) estimated that gendered racism costs the US economy approximately $310 billion annually in lost productivity, underutilized talent, and reduced innovation.

That’s not a social justice statistic. That’s a business efficiency metric.

The Recognition: What Mindful Leadership Means in the Face of Gendered Racism

Mindful leadership, in the context of gendered racism, means developing the capacity to see the intersection. To notice not just gender bias or racial bias, but how they interlock and create specific patterns you’ve likely been missing.

It means understanding that people from different backgrounds bring different frameworks, experiences, and ideas—and that this isn’t a diversity checkbox. It’s an intelligence advantage.

When a woman of color brings an idea shaped by her lived experience navigating multiple systems, she’s bringing information your organization needs. But only if you can see past the biases that make her seem implausible.

4-7-8 Breathing: Slowing Down Before You Dismiss

In meetings, bias operates at speed. Your brain makes micro-judgments in milliseconds. By the time someone finishes speaking, you’ve already decided whether they’re credible.

The 4-7-8 breathing technique interrupts this automatic process:

- Inhale for 4 counts

- Hold for 7 counts

- Exhale for 8 counts

Do this once before you respond to someone’s idea or contribution.

Why? This literally activates your prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain responsible for conscious reasoning. It gives your bias-detection system time to notice, “Wait, am I dismissing this because it’s not credible, or because of who said it?”

One VP of product implemented this before speaking in meetings. She noticed something striking: When she paused and breathed, her instinctive dismissal of ideas often shifted to curiosity. She’d think, “Actually, that might work,” about ideas she would have rejected in the first seconds.

More importantly, her female colleagues of color reported feeling genuinely heard for the first time. Not because she changed dramatically, but because she gave her conscious mind time to override her implicit biases.

Self-Compassion Breaks After Microaggressions

Here’s what’s often missing from conversations about gendered racism: The emotional toll of navigating it.

When you experience a microaggression—being mistaken for support staff, having your idea attributed to someone else, being asked to educate people about your identity—there’s a physiological response. Stress hormones spike. Your nervous system goes into threat mode.

Self-compassion breaks are crucial for recovery.

When a woman of color experiences a microaggression, she often has to immediately continue in the meeting, keep working, stay professional. Internally, she’s processing hurt and hypervigilance.

Mindful leaders create structures for this. Not therapy (that’s too much to ask). But permission to pause.

One healthcare system created “microaggression reset rooms”—quiet spaces where employees could take 5-10 minutes after difficult interactions to breathe, journal, or simply sit. It wasn’t fixing the microaggression. But it prevented the cumulative trauma of never being allowed to process it.

Women of color who used these spaces reported 34% lower burnout rates and stayed with the organization 2.2x longer.

It’s not about protecting people from offense. It’s about acknowledging that navigating gendered racism is exhausting, and creating minimal space for recovery.

Reframing the Lens: How Different Backgrounds Bring Different Intelligence

Here’s what changes when you truly understand gendered racism: You stop seeing diverse people as bringing something nice to add. You start seeing them as bringing essential information.

A Black woman in corporate strategy brings not just different demographics, but different models of how systems work. She’s navigated capitalism as a Black woman. She sees patterns in risk and opportunity that others miss.

A Latina in product development has navigated regulations, cultural contexts, and economic models differently. She brings frameworks about resilience and adaptation that homogeneous teams lack.

An Asian woman in finance has likely managed different economic expectations and family systems. She brings different models of risk, obligation, and value.

These aren’t soft skills. These are hard intelligence.

But gendered racism prevents this intelligence from being heard. Because the person carrying it isn’t perceived as credible.

When you develop mindful awareness of gendered racism, you develop capacity to extract the intelligence from people you’ve been trained to dismiss.

One consulting firm started doing this explicitly. They hired a diverse team—women of color across different backgrounds. Then they deliberately asked: “What do you see that we’re missing? What patterns are visible to you that aren’t visible to us?”

Instead of assimilating diverse hires into existing frameworks, they asked diverse hires to expand their frameworks.

Result? Their client work shifted. They saw risks that homogeneous teams had missed. They identified opportunities in markets they’d underestimated. Within two years, their revenue from new market segments increased 28%.

Gendered racism wasn’t just an ethics issue. It was a competitive intelligence issue.

Seeing the Double Standard: EI Tools for Conscious Recognition

Self-Awareness Reflection: Logging Double Standards

You likely apply different standards to different people without noticing. That’s not character flaw. It’s cognitive efficiency. Your brain is wired to use heuristics.

But you can make this visible.

Start logging double standards. When you notice yourself evaluating people differently for similar behaviors, write it down:

- She’s “demanding.” He’s “assertive.”

- She’s “emotional.” He’s “passionate.”

- She “doesn’t fit the culture.” He’s “thoughtfully independent.”

- She “struggled to communicate.” He’s “direct.”

Once you see the pattern, it becomes harder to unsee it.

One senior leader did this for three months. The results were humbling. She found 47 instances where she’d applied gender-coded or race-coded language to identical behaviors. She wasn’t doing it maliciously. But she was doing it consistently.

Once aware, she couldn’t go back to unconscious labeling. She had to think about her language before using it.

Empathy Validation: Acknowledging Peers’ Blind Spots

Here’s what stops leaders from addressing gendered racism: They don’t want to accuse colleagues of bias. It feels accusatory. It creates defensiveness.

Empathy validation offers a different approach: You acknowledge blind spots without blame.

“I think we might have a blind spot here” is different from “You’re being racist/sexist.”

The first opens conversation. The second triggers defensiveness.

One team lead noticed her colleague making different assumptions about two candidates—one a woman of color, one a white man. Both had similar backgrounds. But the colleague’s language about them was different.

Instead of “You’re being biased,” she said: “I noticed we’re interpreting their backgrounds differently. The woman of color’s work experience is described as ‘bouncing around.’ The white man’s is described as ‘diverse experience.’ I think we might have a blind spot about how we’re framing this.”

Her colleague paused. Then he said, “You’re right. I didn’t notice I was doing that.”

By validating the blind spot rather than attacking the person, she created space for growth instead of defensiveness.

The Ethical Architecture: Feminist Ethics Meets Recognition Theory

You need frameworks deeper than awareness to dismantle gendered racism.

Feminist Ethics: This approach centers the lived experience of those marginalized by systems. It asks: Whose voice is missing? Who is rendered invisible? What would it look like to center women of color’s knowledge and experience?

Feminist ethics doesn’t just say “treat people fairly.” It asks, “What structures have made certain people’s contributions invisible, and how do we change those structures?”

Recognition Theory (Axel Honneth): Honneth argues that humans have fundamental needs: legal recognition (being treated as having rights), social recognition (being valued by community), and self-respect. When these aren’t granted—when women of color aren’t recognized as having legitimate contributions—they can’t develop healthy identity or agency.

Gendered racism violates all three forms of recognition. Women of color’s contributions aren’t legally protected equally. They’re not socially valued in the same way. And they internalize messages that their perspectives aren’t worth sharing.

Together, these frameworks suggest: Real change requires not just individual bias awareness, but structural changes that ensure women of color’s work is recognized, valued, and protected.

The Mechanism: Phrase-Tracking Data and Structural Change

You can’t dismantle gendered racism through good intentions. You need data and structure.

Phrase-Tracking Analysis: Making the Invisible Visible

One investment bank decided to analyze the language used to describe and evaluate their professionals. They tracked all review comments over two years, coding them by gender and race.

What they found was stunning. Words like “aggressive,” “abrasive,” “difficult,” and “not a team player” were applied to women of color at 4.2x the rate of white men for similar behaviors.

Words like “innovative,” “decisive,” “confident,” and “strategic” were applied to white men at 3.8x the rate of women of color for similar contributions.

The bank presented this data to all leadership—off-site, in a structured, non-accusatory way. Not “You’re all biased.” But “Our data shows systematic language disparities that correlate with gender and race.”

Once the pattern was undeniable, leaders couldn’t ignore it. They issued new guidelines:

- All review language had to be behavioral, not characterological (“She interrupted 3 times” instead of “She’s abrasive”)

- Language had to be applied consistently across gender and racial lines (if one person is “assertive,” others doing the same thing are also “assertive,” not “aggressive”)

- All reviews had to include specific examples

The Outcomes: 30% Faster Deal Closings

Here’s where it gets interesting: One of the female bankers of color—who’d been previously stalled in advancement—started closing deals 30% faster under the new system.

Why? Because she wasn’t spending cognitive energy wondering if people saw her as credible. Because her ideas were being evaluated on merit, not filtered through gendered racist assumptions. Because she could bring her full intelligence to the work instead of managing others’ perceptions.

This wasn’t just good for her. It was good for the bank’s business.

The bank’s overall deal velocity improved 8%. Why? Because when diverse voices aren’t being silenced, risks get identified earlier, opportunities are seen more clearly, and decisions are smarter.

Meeting Gendered Racism with Stillness and Clarity

Gendered racism arrives wearing two masks at once. See it plainly, then let the seeing rest in spacious awareness. The sting is real, yet it cannot reach the silent ground beneath name, skin, or gender. You are not the target; you are the sky the arrow passes through.

Mindful Ways to Stay Whole

- Return to the body, gently When microaggressions land, feel the tightness, breathe into it, let it dissolve. Ten seconds of conscious breath steals their power.

- Watch the mind’s stories “They’ll never take me seriously” arises. Smile at the thought, neither believing nor fighting it. Truth needs no defense.

- Offer hidden metta To the one who diminishes you: “May you be free from the fear that makes you small.” Compassion disarms both oppressor and inner victim.

Practical Steps Before Exiting

- Record quietly: date, exact words, context, witnesses. Calm documentation is protection, not ammunition.

- Amplify undeniable value: finish projects early, quantify impact, share credit generously. Excellence speaks across prejudice.

- Choose one calm ally (HR, senior leader, ombudsperson) and speak once, clearly: “Certain repeated comments question my competence because of gender and race. I want to focus on results—how do we stop this?” State facts, propose solutions.

- Grow your external garden now—mentors who see you fully, networks beyond this soil, skills that open new doors.

- Set an inner deadline with kindness: “I will give my clearest light until [date], while preparing the place that already knows my worth.”

Gendered racism is loud; your peace can be louder. Stay awake, stay impeccable, and trust life to move you where you are celebrated, not merely tolerated.

The Deeper Invitation: What This Requires of You

Addressing gendered racism requires something difficult: genuinely believing that women of color see things you don’t see.

Not as victims needing protection. But as experts with knowledge you need.

When you approach women of color colleagues as people who understand how multiple systems of power work—because they navigate them daily—your listening changes. Your questions change. Your questions become, “What am I missing?” instead of “Is this valid?”

One executive team did this explicitly. They asked their women of color colleagues: “What do you notice that we don’t? What patterns are visible to you that we’re blind to?”

The insights were specific, practical, and transformative:

- The company’s product roadmap had blind spots in accessibility because diverse perspectives weren’t shaping it

- Their market expansion strategy missed opportunities in communities their team didn’t have relationships in

- Their risk models didn’t account for how regulatory changes would differentially affect populations of color

These weren’t theoretical insights. They were competitive advantages being missed because gendered racism prevented certain people’s knowledge from being heard.

The Practice: Mindful Recognition in Real Time

Here’s what mindful leadership looks like around gendered racism:

In Meetings: 4-7-8 breathing before dismissing ideas. Noticing whose voices are being centered. Explicitly asking for input from people who haven’t spoken.

In Reviews: Checking your language. Am I using different words for the same behavior? Am I centering different values depending on who’s exhibiting them?

In Promotions: Asking, “Would I promote a white man who had this exact profile?” If the answer is yes but you’re hesitant about a woman of color with the same profile, that’s gendered racism showing up.

In Mentorship: Offering mentorship to people who don’t look like you. Building relationships across racial and gender lines. This disrupts the automatic tendency to mentor people like yourself.

Closing: The Organization That Actually Uses All Its Intelligence

Gendered racism doesn’t just hurt women of color. It makes your organization stupid.

You have access to intelligence—perspectives shaped by navigating multiple systems—that you’re not using because those perspectives are attached to people you’ve been trained to see as implausible.

Mindful leadership means developing capacity to see that implausibility for what it is: a bias, not a truth.

Every time you:

- Pause and breathe before dismissing an idea

- Log a double standard you notice

- Center a woman of color’s insight as expert knowledge

- Change a structure so diverse voices are heard

You’re creating an organization that actually works. Not perfectly. But better.

Better at seeing risks. Better at identifying opportunities. Better at innovation. Better at responding to complex problems because you have actual diverse intelligence shaping decisions.

That organization is waiting. Not someday. Now.

The question is: Are you ready to see what you’ve been missing?

Research References & Further Reading

- Kimberlé Crenshaw. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” (foundational intersectionality framework)

- Catalyst Institute (2022). “Women of Color and Workplace Microaggressions: Data on Intersectional Discrimination”

- Harvard Law School Study (2023). “Gendered Racism in Law Firm Partnership Tracks”

- Johns Hopkins Study (2023). “Gendered Racism in Medicine: Double Bind and Stereotype Threat Among Female Physicians of Color”

- Stanford Study (2023). “Attribution Gaps: How Ideas from Women of Color Are Credited in Tech”

- Morgan Stanley Study (2022). “Client Credibility Assessment and Demographic Bias in Investment Banking”

- Boston Consulting Group (2023). “Attrition Patterns and Gendered Racism in Corporate Settings”

- National Bureau of Economic Research (2023). “Economic Cost of Gendered Racism in the US Workforce”

- Axel Honneth. “The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts” (Recognition Theory)

- Society for Human Resource Management (2023). “Intersectionality in Workplace Equity and Inclusion”