Laid off? Launch failed? Lost it all? Here’s the failure autopsy that extracts wisdom without self-destruction—and gets you back in the game stronger

You got laid off.

Or the startup you poured three years into just imploded. Or the product launch you believed in crashed spectacularly. Or the relationship you were certain would last ended abruptly.

You’re sitting in the wreckage, scrolling through LinkedIn watching everyone else announce promotions, funding rounds, and wins. Meanwhile, you’re wondering if you’ll ever recover from this.

Here’s what I need you to know: this moment—this exact feeling of total collapse—is not the end of your story. It’s the data point that changes everything.

But only if you learn to do something most people never figure out: extract the lesson without extracting your self-worth.

Why We Fear Failure: The Psychology of Falling Down

Research demonstrates that fear of failure arises from learned experiences, typically formed in childhood and manifesting as the tendency to avoid situations where failure is possible due to anticipated shame, humiliation, or embarrassment.

But here’s what makes failure uniquely terrifying in modern life: we’ve conflated failure with identity.

You don’t just experience failure—you become it. Your LinkedIn profile becomes a scarlet letter. Your résumé has a gap. Your pitch deck is evidence of your inadequacy.

Studies show that even a single experience of failure can heighten anxiety and depression, with perceptions of failure implicated in a range of psychological disorders. The stakes feel existential because we’ve made them existential.

The Two Faces of Fear

Psychological research identifies two distinct patterns in how people respond to failure: overstriving (working relentlessly to avoid failure) and self-protection (avoiding situations where failure is possible). Both render you uncertain, anxious, and vulnerable.

The overstriv you works eighty-hour weeks, terrified that slowing down means falling behind. The self-protecting you never launches, never applies, never risks—because if you don’t try, you can’t fail.

Neither version thrives. Both are cages.

I know a founder—call her Zara—who raised seed funding, built a team of twelve, and launched a product that nobody wanted. She burned through her runway in eighteen months. When the company died, she spent six months on her couch, unable to even update her LinkedIn.

“I couldn’t separate the failure of my company from my identity,” she told me later. “If the company was worthless, I was worthless. I thought I’d never work again.”

That’s the trap. And it’s entirely avoidable.

Gracefully Accepting Failure: The Art of Holding Both Truths

Before you can learn from failure, you have to stop fighting with reality.

Acceptance doesn’t mean you’re happy about what happened. It means you acknowledge what is true without drowning in what it means about you.

The Practice of Radical Acknowledgment

Carol Dweck’s research emphasizes that in a growth mindset, failure can be a painful experience, but it doesn’t define you—it’s a problem to be faced, dealt with, and learned from.

Write this down: “This happened. It hurts. And I’m still here.”

Not: “This is the worst thing that could happen.”

Not: “I’m ruined forever.”

Just: “This happened. It hurts. And I’m still here.”

Two Truths Can Coexist

You can hold both of these truths simultaneously:

- This failure is genuinely painful and represents real loss

- This failure does not determine your worth or future potential

When Zara finally emerged from her couch, she practiced this daily: “My company failed AND I learned things that will make my next venture stronger. I lost money AND I gained clarity. I feel devastated AND I’m capable of rebuilding.”

The “AND” is everything. It prevents collapse into either toxic positivity (“everything happens for a reason!”) or toxic negativity (“I’m doomed forever”).

The Neuroscience of Letting Go

Your brain wants to solve the problem of failure by either justifying it away or catastrophizing it. Neither helps.

What does help: acknowledging the emotional reality without making it permanent.

Research shows that emotion regulation serves as a crucial mediator between fear of failure and psychological well-being, with individuals who can effectively regulate emotions experiencing better outcomes after setbacks.

Feel the grief. Sit with the disappointment. Name the shame. Then stand up anyway.

How to Rebound: The Four-Phase Failure Recovery Framework

Rebounding from failure isn’t about bouncing back quickly. It’s about extracting every ounce of wisdom before moving forward.

PHASE 1: THE ACKNOWLEDGMENT PERIOD (Days 1-7)

Immediately after a major setback, you’re in emotional freefall. This is not the time for analysis. This is the time for basic survival and emotional processing.

What to do:

- Cancel non-essential commitments for one week

- Tell three trusted people what happened

- Move your body daily (walk, run, anything that shifts your state)

- Journal without editing: What happened? How do you feel?

- Resist the urge to immediately apply for new jobs, start new projects, or make big decisions

What not to do:

- Make permanent decisions based on temporary emotions

- Isolate completely

- Numb out with substances, screens, or compulsive work

- Compare your inside to others’ outsides on social media

Zara’s first week after her company failed: “I cried. I slept. I walked my dog. I told my partner everything. I didn’t try to be productive. I just survived.”

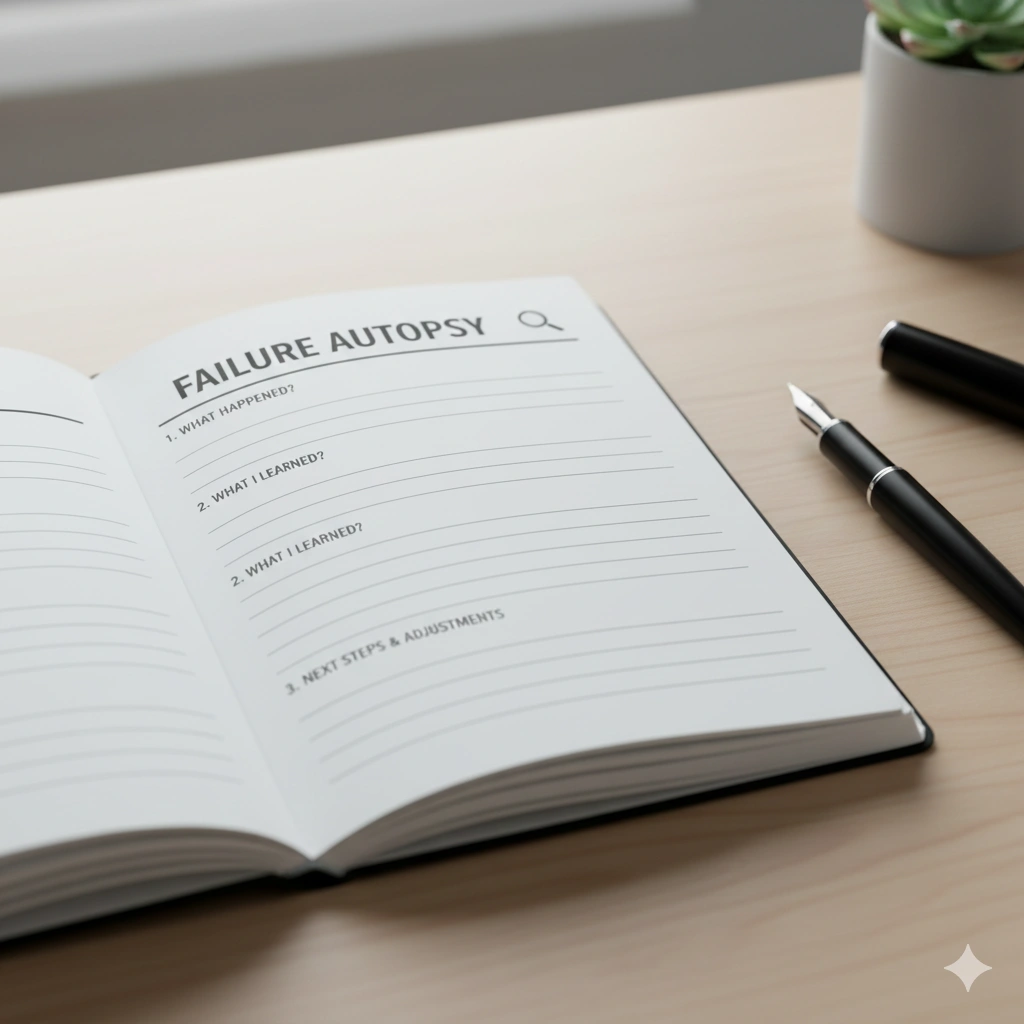

PHASE 2: THE FAILURE AUTOPSY (Weeks 2-4)

Now you’re ready for the structured analysis. This is where most people skip ahead too fast or avoid entirely. Both are mistakes.

The Failure Autopsy Template:

1. What actually happened? (Facts only, no interpretation)

- Timeline of events

- Decisions made

- External factors

- Internal factors

2. What were my assumptions? (What did you believe that turned out to be wrong?)

- About the market

- About yourself

- About timing

- About resources

3. What were early warning signs I missed?

- Red flags you ignored

- Feedback you dismissed

- Intuition you overrode

4. What was within my control?

- Decisions you made

- Actions you took

- Patterns you repeated

5. What was genuinely outside my control?

- Market shifts

- Timing

- Other people’s choices

- Unforeseeable circumstances

6. What skills did I demonstrate even in failure?

- What you built

- What you learned

- What you endured

- Who you became

7. What would I do differently with identical resources and knowledge at the time? (Not with hindsight—with what you actually knew then)

This distinction is critical. Hindsight makes everything obvious. The question is: what could you have reasonably known or done differently at that moment?

Zara’s autopsy revealed: “I raised too much too fast and felt pressure to scale before we had product-market fit. I ignored three customers who told me directly the product wasn’t solving their actual problem. I hired for credentials over cultural fit. AND I also faced a market downturn that made fundraising impossible for companies like mine.”

Notice: some was her responsibility, some wasn’t. Both can be true.

PHASE 3: THE EXTRACTION (Months 2-3)

Now you convert the autopsy into actionable wisdom.

Ask yourself:

What is this failure teaching me about…

- My decision-making patterns?

- My blind spots?

- My values?

- My risk tolerance?

- My support systems?

- My resilience capacity?

Create your “Never Again” list:

Not in judgment, but in clarity. What patterns will you actively work to change?

Examples from Zara:

- “I will never again scale a team before validating product-market fit”

- “I will never again dismiss customer feedback that contradicts my vision”

- “I will never again raise more money than I need just because it’s available”

Create your “More Of This” list:

What did you do well, even in failure?

Zara’s list:

- “I communicated transparently with my team when things got hard”

- “I sought mentorship even when I felt ashamed”

- “I maintained ethical practices even under financial pressure”

PHASE 4: THE REINTEGRATION (Month 3+)

Now you re-enter the arena—but differently.

What reintegration looks like:

- Applying for roles with clarity about what you actually want

- Starting new projects with lessons integrated, not trauma driving

- Taking calculated risks informed by experience, not paralyzed by fear

- Building support systems before you need them

- Setting boundaries you didn’t have before

Carol Dweck’s research shows that individuals with growth mindsets don’t fear failure as intensely because they realize performance can be improved and learning comes from failure—this mindset allows people to live less stressful and more successful lives.

Zara eventually joined another startup as VP of Product. “I bring so much more now,” she said. “I know what dying companies look like from the inside. I know which metrics matter. I know when to trust my gut. The failure didn’t make me weaker—it made me valuable.”

Practical Tips to Analyze Shortcomings and Become Stronger

Beyond the four-phase framework, here are specific practices that transform setbacks into strength:

The “Five Whys” Technique

When you identify something that went wrong, ask “why” five times to get to the root cause.

Example:

- The product failed. Why? → We didn’t have enough users.

- Why didn’t we have enough users? → Our marketing wasn’t effective.

- Why wasn’t marketing effective? → We didn’t understand our target customer.

- Why didn’t we understand them? → We built the product before validating the problem.

- Why did we build before validating? → I was afraid of wasting time on research and wanted to move fast.

Root cause: Fear-driven decision-making instead of evidence-based.

The Resilience Factors Assessment

Systematic research on resilience to failure identifies specific buffering factors: higher self-esteem, more positive attributional style, and lower socially-prescribed perfectionism show the strongest evidence for conferring resilience to emotional distress after failure.

Evaluate yourself:

- Self-esteem: Do I derive worth from what I do or from who I am?

- Attributional style: Do I see failures as permanent, pervasive, and personal—or temporary, specific, and changeable?

- Perfectionism: Am I driven by internal standards or external validation?

These factors aren’t fixed. They’re skills you can develop.

The Comparison Reframe

Stop comparing your failure to others’ success. Instead, compare your current self to your past self.

Questions to ask:

- What can I do now that I couldn’t do a year ago?

- What do I know now that I didn’t know then?

- What have I survived that I once thought would destroy me?

This reframe moves you from scarcity (“everyone’s ahead of me”) to growth (“I’m building capacity”).

The Mentor Mirror

Find someone who’s failed publicly and recovered. Study their path. Ask for their insights.

Most successful people have catastrophic failures in their past. They just don’t lead with them. Seek those stories out. They’re your roadmap.

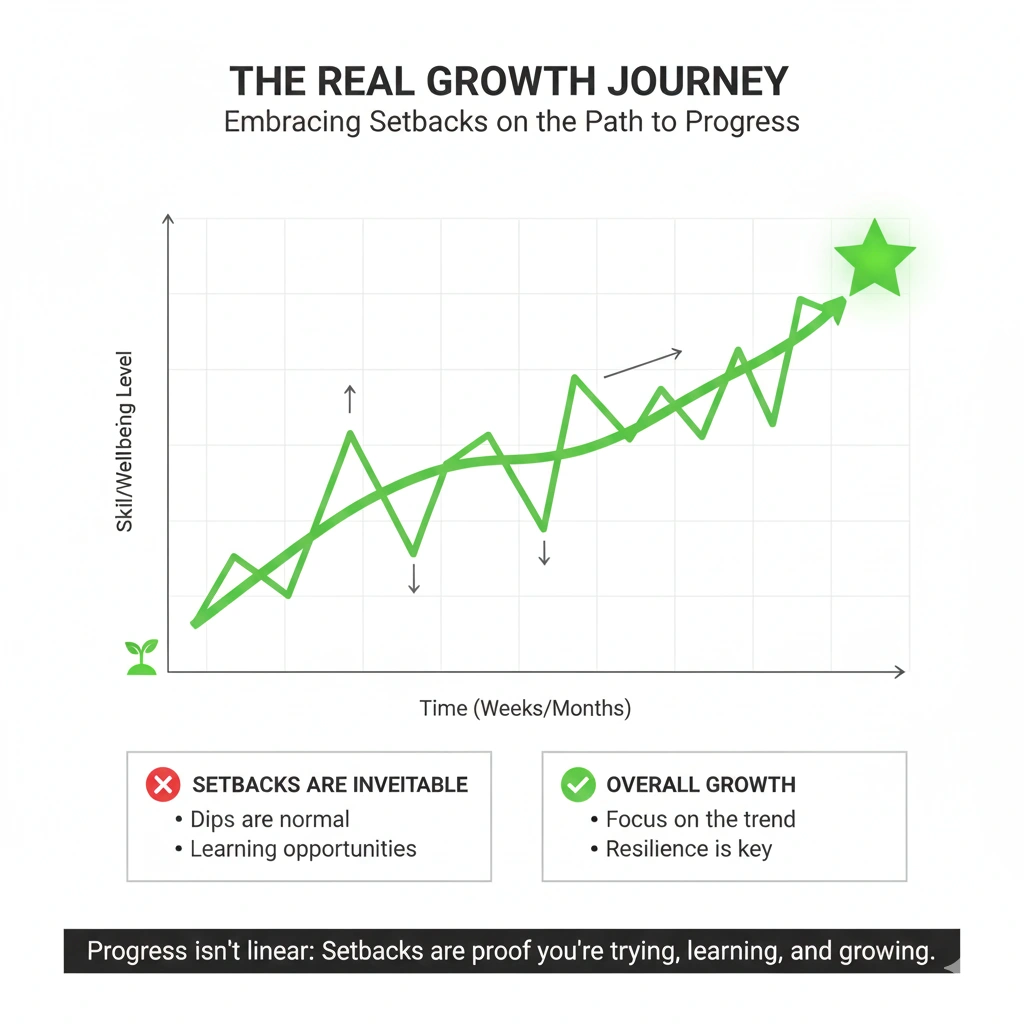

Not Giving Up: The Practice of Persistent Presence

Resilience isn’t about never falling down. It’s about standing back up one more time than you fall.

The “Not Yet” Principle

Carol Dweck’s research introduces the concept of “not yet”—reframing failure not as permanent defeat but as a point on a continuum of learning, helping students and professionals see that they simply haven’t mastered something yet, rather than viewing themselves as incapable.

You didn’t fail. You haven’t succeeded yet.

The product didn’t work. You haven’t found product-market fit yet.

You lost that opportunity. You haven’t found the right opportunity yet.

The Micro-Comeback Strategy

Don’t try to rebuild everything at once. Choose one small action that represents forward movement.

Examples:

- Update your LinkedIn

- Reach out to one person in your network

- Apply to one job

- Write one page of your next idea

- Take one course

Each micro-action rebuilds your sense of agency. You’re not stuck. You’re regrouping.

The Evidence Journal

Every day, write down one piece of evidence that you’re capable:

“Today I [specific action]. This proves I can [larger capability].”

“Today I sent three networking emails. This proves I can still take initiative.”

“Today I finished the online course. This proves I can still learn.”

You’re not trying to feel confident. You’re building evidence that confidence is justified.

Common Pitfalls That Keep You Trapped

Pitfall 1: Skipping the Grief

You can’t think your way out of emotional pain. If you skip the grief phase and jump straight to productivity, the unprocessed emotion will sabotage you later.

Feel it. All of it. Then move.

Pitfall 2: Making It Mean Everything

One failure doesn’t define your trajectory. Research shows that students with fear of failure often engage in procrastination as a defense mechanism, using it to protect themselves from confronting their capacity—but this avoidance perpetuates the cycle rather than resolving it.

Don’t let one setback convince you to stop trying. That’s when failure becomes permanent.

Pitfall 3: Isolating

Shame thrives in isolation. The more you hide your failure, the more power it has over you.

Tell people. Not everyone—but the right people. The ones who’ve fallen and gotten back up.

Pitfall 4: Rushing the Rebound

There’s a difference between resilience and denial. If you immediately jump into the next thing without processing this thing, you’re just carrying the same patterns forward.

Take the time. Do the autopsy. Extract the wisdom.

Pitfall 5: Waiting for External Validation

You don’t need someone to hire you, fund you, or choose you to prove you’re worthy of trying again.

You give yourself permission to reenter. Nobody else.

Conclusion: The Scar Is the Proof

Two years after her company failed, Zara launched a new venture. This time, she validated the problem first. She hired slowly. She raised conservatively. She listened to customers.

The company isn’t a unicorn. But it’s profitable, sustainable, and solving a real problem. And Zara sleeps at night.

“I wouldn’t have built this version without failing at the first one,” she told me. “The failure gave me clarity I could never have gotten any other way. I don’t regret it. I’m grateful for it.”

That’s the goal: not to avoid failure, but to metabolize it so completely that it becomes fuel.

Your crash is not the end. It’s the compression before the launch.

The knowledge you gained? That stays. The resilience you built? That’s permanent. The humility you earned? That’s your competitive advantage.

Every successful person you admire has failed spectacularly. The difference isn’t that they didn’t fall—it’s that they learned to fall forward.

Your Failure Autopsy Starts Now

If you’re in the wreckage right now, here’s your first action:

Open a document. Title it: “What [this failure] taught me.”

Write down:

- What actually happened (facts only)

- What I’m feeling right now (emotions, unedited)

- One thing I learned

- One thing I’ll do differently

- One reason I’m still capable

That’s it. Five lines. That’s how you begin.

The scar is the proof you survived something that could have destroyed you.

Wear it. Learn from it. Launch from it.

You’re not done. You’re just getting started.

Your Failure Recovery Checklist:

□ Acknowledge what happened without catastrophizing

□ Take 1 week for emotional processing before analysis

□ Complete the failure autopsy template

□ Identify 3 specific lessons extracted

□ Create “Never Again” and “More Of This” lists

□ Take one micro-action toward forward movement

□ Connect with one person who’s recovered from failure

□ Reframe: I haven’t succeeded yet

Final Thought:

The crash is not the end of your trajectory. It’s the data point that makes you wiser, sharper, and more valuable.

Extract the lesson. Release the shame. Launch forward.

You haven’t failed. You’re learning. And learning always wins eventually.

Research References:

- Conroy, D. E., & Elliot, A. J. (2004). “Fear of failure and achievement goals in sport.” In G. Roberts & R. Treasure (Eds.), Advances in Motivation in Sport and Exercise. Human Kinetics.

- Johnson, J., Wood, A. M., Gooding, P., Taylor, P. J., & Tarrier, N. (2011). “Resilience to suicidality: Psychometric properties of a questionnaire.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(11), 717-726.

- Balkis, M., & Duru, E. (2019). “Procrastination and rational/irrational beliefs: A moderated mediation model.” Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 37(3), 299-315. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10212-024-00868-9

- Panagioti, M., Gooding, P. A., & Tarrier, N. (2012). “A meta-analysis of the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidality: The role of comorbid depression.” Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(7), 915-930. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735816302902

- Panagioti, M., Gooding, P., Taylor, P. J., & Tarrier, N. (2014). “Perceived social support buffers the impact of PTSD symptoms on suicidal behavior.” Journal of Affective Disorders, 159, 104-112. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27918887/

- Chuang, S. P., Huang, S. J., Lin, Y. J., & Chen, Y. L. (2022). “The influence of motivation, self-efficacy, and fear of failure on the career adaptability of vocational school students: Moderated by meaning in life.” Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 938782. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9534183/

- Martin-Krumm, C., Sarrazin, P., & Peterson, C. (2005). “The moderating effects of explanatory style in physical education performance: A prospective study.” Personality and Individual Differences, 38(7), 1645-1656.

- Mehdi, S. A., & Singh, L. B. (2025). “Effect of entrepreneurial fear of failure: A moderated mediation model of resilience and emotion regulation.” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/jeee-08-2024-0325/full/pdf

- Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2004). “The intergenerational transmission of fear of failure.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 957-971.

- Vaughn, A. A., et al. (2021). “Self-handicapping as a maladaptive coping strategy.” Journal of Personality, 89(5), 897-913.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House. https://fs.blog/carol-dweck-mindset/

- Dweck, C. S. (2015). “Carol Dweck revisits the ‘growth mindset.'” Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/opinion-carol-dweck-revisits-the-growth-mindset/2015/09

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). “A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality.” Psychological Review, 95(2), 256-273. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carol_Dweck

- Moser, J. S., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y. H. (2011). “Mind your errors: Evidence for a neural mechanism linking growth mindset to adaptive post-error adjustments.” Psychological Science, 22(12), 1484-1489.

- Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). “Mindsets: A view from two eras.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481-496. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6594552/

- Nussbaum, A. D., & Dweck, C. S. (2008). “Defensiveness versus remediation: Self-theories and modes of self-esteem maintenance.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(5), 599-612.

- Boaler, J. (2016). Mathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students’ Potential Through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching. Jossey-Bass. https://www.targetx.com/blog/failure-is-the-only-option-embracing-a-growth-mindset/

- White Horse, E. (2025). “Success versus failure and the ‘not yet’ principle.” Dr. Emily White Horse Blog. https://www.dremilywhitehorse.com/blog/success-versus-failure-and-the-not-yet-principle

- Student Experience Research Network. (2021). “Carol Dweck Research Overview.” https://studentexperiencenetwork.org/people/carol-dweck/

Williams, N. B. (2023). “Failing forward: Helping undergraduate researchers cultivate resilience.” In Confronting Failure: Approaches to Building Confidence and Resilience. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED621426.pdf