Year 5, zero papers, funding ends in 6 months. Here’s what actually helps.

You stare at the email. Subject: “Re: Manuscript Draft 4.” You don’t need to open it to know. The red-tracked comments will cover every paragraph like bloodstains. “Unclear reasoning.” “Needs more references.” “This doesn’t address the core question.”

You’ve spent three months on this draft. Three months of sixteen-hour days, skipped meals, canceled plans, promises to yourself that “this time it’ll be good enough.”

It wasn’t.

You’re in year five. You have zero published papers. Your funding ends in six months. Your friends from undergrad are buying houses, getting promoted, starting families. You’re eating instant noodles and wondering if you’re smart enough to be here at all.

Welcome to the PhD crisis that nobody warned you about. Research reveals that PhD and master’s students worldwide report rates of depression and anxiety six times higher than the general public, with more than 40% showing moderate to severe anxiety and nearly 40% experiencing moderate to severe depression. Another study found that 36% of PhD students sought help for anxiety or depression caused by their studies.

This isn’t another motivational piece about “perseverance” or “passion for research.” This is about how you survive when your supervisor crushes your confidence weekly, when imposter syndrome whispers constantly, and when the finish line keeps moving further away.

The Five Demons Every PhD Student Battles

1. “The Imposter Spiral: When Everyone Seems Smarter Except You”

Picture this: You’re in a lab meeting. Your colleague casually mentions a methodology you’ve never heard of. Another student references a paper everyone apparently knows except you. The visiting professor asks a question about your research, and your mind goes completely blank.

Later, alone in your office, the voice starts: “You don’t belong here. You got in by luck. They’ll figure it out soon.”

Research shows that 50.6% of PhD students believe they suffer from imposter phenomenon, with studies revealing that imposter syndrome can endanger doctoral students’ academic advancement and psychological well-being. Studies found that perceived belongingness negatively predicts imposter syndrome, which in turn predicts higher levels of depression, stress, and illness symptoms.

One student described the feeling: “In both cases where I have been first author on a publication, I have felt like I cheated my way through it.” Another shared: “I wasn’t feeling like I belonged in the program. Now I have to teach those students. That really made me feel like an impostor.”

You’re surrounded by brilliant people. You see their successes on Twitter, their publications in journals, their conference presentations. What you don’t see: their rejected papers, failed experiments, and 3 AM panic attacks.

What Actually Works

The 5-Minute “PI-from-Space” Perspective Exercise

When imposter syndrome hits hardest, your brain zooms in on every mistake, every gap in knowledge. This practice zooms out—way out—to reset your perspective.

Here’s how:

Minutes 1-2: Earth Level

- Close your eyes

- Breathe slowly (4 counts in, 6 counts out)

- Picture yourself in your current space—office, lab, library

- Acknowledge the stress: “I feel inadequate right now”

Minutes 3-4: Space Level

- Zoom out in your mind’s eye

- See your building from above

- See your city

- See your country

- See Earth from space—a pale blue dot

Minute 5: Perspective Shift

- From space, your failed experiment doesn’t exist

- Your supervisor’s criticism doesn’t exist

- Your perceived inadequacy doesn’t exist

- But you do. You’re still here. Still trying.

- Say aloud: “I’m one human, doing difficult work, and that’s enough”

This isn’t about minimizing your work—it’s about right-sizing your anxiety. Your worth isn’t measured by whether you impress your PI today.

Reframe Imposter Syndrome as Evidence of Growth

If you never feel lost, you’re not learning anything new. Studies reveal that PhD students experience imposter feelings especially when: teaching new topics, using unfamiliar methods, presenting research, or writing for publication. These are precisely the moments you’re expanding your expertise.

The Beginner’s Qualification Mindset

One expert notes: “A PhD is a beginner’s qualification. It is during your PhD that you develop basic research skills.” You’re not supposed to know everything. You’re supposed to be learning. Big difference.

Research Reference

Comprehensive review of imposter phenomenon among doctoral students reveals it’s linked to perfectionism, loneliness, poor student-supervisor relationships, and fear of failure, with consequences including depression, stress, and academic underperformance. Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10581342/

2. “The Moving Goalpost Marathon: When ‘Just One More Experiment’ Never Ends”

Your supervisor says: “This is good progress. Just refine the methodology and we’ll submit.”

Three months later: “Actually, let’s add another dataset.”

Six months later: “We need to completely restructure the argument.”

Year later: “I think we should start fresh with a different approach.”

You’re running a marathon where someone keeps moving the finish line. Research shows that time demands of lengthy experiments lead to unpredictable working hours, skewing work-life balance and creating loss of control, while pressures of time and funding take a toll especially in countries with short PhD programs.

Nature’s PhD survey found that 27% of respondents spend 41-50 hours weekly on their PhD, with a quarter spending 51-60 hours, and almost 20% holding additional jobs to make ends meet.

One student described the reality: “Work-life balance is hard to attain in a culture where it is frowned upon to leave the laboratory before the sun goes down.”

Your undergraduate friends work 9-5 and then actually stop working. You work from when you wake up until you collapse. Weekends don’t exist. Vacations feel like betrayal. Every hour not working is an hour falling further behind.

What Actually Works

Establish Concrete Milestones with Your Supervisor

Schedule a meeting specifically to define: What does “good enough” look like? Write it down. Get them to commit.

Example conversation: “For this paper to be submittable, I understand we need: [X dataset], [Y analysis], [Z structural changes]. If I complete these by [date], can we commit to submission? What would prevent that?”

Document their answer. When goalposts move, gently remind them of this conversation.

The PhD Is Training, Not Your Magnum Opus

Your dissertation doesn’t need to solve every problem in your field. It needs to demonstrate research competence. That’s it. Good enough is good enough.

Forced Boundaries (Non-Negotiable)

The Evening Shutdown (6 PM or 8 PM—pick one)

- Close laptop

- Change clothes

- Leave the building/office

- No email checking for 12 hours minimum

“But my experiment runs until midnight!” — Set it up so you can leave. Automation exists for a reason.

The Sunday Sanctuary

Complete work shutdown

- Not “reduced hours”—complete shutdown

- Your brain needs actual recovery, not just working from home instead of office

Weekly “Small Win Friday” Thread with Lab Mates

Every Friday afternoon, text three lab mates. Share one small win from the week:

- “Finally got that Western blot to work”

- “Wrote 500 words without hating them”

- “Read a paper that actually helped”

- “Didn’t cry in the bathroom this week”

This practice serves three purposes:

- Forces you to notice progress (your brain naturally focuses on failures)

- Creates community and shared struggle

- Normalizes celebrating small victories in a culture that only celebrates publications

Studies show that 56% of graduate students experiencing anxiety and 55% experiencing depression said they did not agree with having good work-life balance, while 50% said they didn’t agree that their principal investigator was a role model.

Research Reference

Nature survey of 5,700 PhD students found that although three-quarters were satisfied with their programs, over a quarter saw mental health as a concern, with long hours culture, work-life balance issues, and time pressures identified as primary stressors. Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41556-018-0085-4

3. “The Publication Pressure Cooker: When Your Career Hangs on Reviewer #2”

You finally submit your paper. Six months of work. You cautiously feel hopeful.

Three months later, reviews arrive:

Reviewer 1: “Accept with minor revisions” Reviewer 2: “This work is fundamentally flawed. The authors clearly don’t understand [basic concept you spent two years studying]. Reject.” Reviewer 3: “Requires major revisions”

Decision: Reject.

You’re in year four. You need publications for job applications. Your funding expires in eight months. This was supposed to be “the one.” Research on graduate student mental health shows that 41% scored as having moderate to severe anxiety while 39% scored in moderate to severe depression range, with career development and publication pressure identified as major stressors.

The academic job market is brutal. Every position gets three hundred applications. Without publications, you’re invisible. With publications, you’re maybe visible. The pressure is existential: publish or perish isn’t a metaphor—it’s your reality.

Meanwhile, your supervisor publishes regularly. They don’t seem stressed. They tell you “persistence is key” and “reviews are part of the process.” Easy to say when their career isn’t hanging by a thread.

What Actually Works

Destigmatize Rejection as Data, Not Verdict

Every successful academic has a folder of rejections. Publications you see represent maybe 30-40% of what was submitted. The other 60-70%? Rejected, resubmitted elsewhere, or abandoned.

Rejection means: “This wasn’t right for this journal at this time with these reviewers.” Not: “You’re not cut out for research.”

The Rejection Ritual

When a harsh rejection arrives

- Allow the grief (24 hours): Feel terrible. It’s okay.

- Extract useful feedback (48 hours later): What criticism is actually valid? Ignore personal attacks.

- Revise with clarity: Address legitimate concerns.

- Resubmit elsewhere: Different journal, fresh reviewers.

Diversify Your “Success” Metrics

If publications are your only measure of progress, you’ll suffer. Add other metrics:

- Conference presentations (accepted? Success.)

- Skills developed (learned new software? Success.)

- Chapters written (completed drafts? Success.)

- Mental health days taken (prioritized wellbeing? Huge success.)

Talk About Rejections Openly

Start conversations: “I got rejected from [journal] today. Has anyone else submitted there?”

When senior researchers share their rejection stories, imposter syndrome loses power. Turns out everyone struggles—they just hide it better.

Set Realistic Publication Goals

One paper per year is reasonable. Two is great. Five is unrealistic for most PhD students. Quality over quantity. One well-done paper beats three rushed ones.

Research Reference

Research on mental health in PhD programs identifies publication pressure, fear of failure, and professional development uncertainty as significant contributors to anxiety and depression, with students lacking adequate career guidance reporting worse outcomes. Source: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/03/180307095158.htm

4. “The Supervisor Lottery: When Your PI Is Part of the Problem”

Your supervisor cancels meetings. Again. You’ve been trying to schedule for three weeks. When you finally meet, they spend twenty minutes on email while you sit there, then say: “So where were we? Remind me what you’re working on?”

You’ve explained your project seventeen times.

Or maybe it’s the opposite: micromanagement. They want daily updates, question every decision, reject every idea you propose, and somehow your research never quite measures up to their vision—which changes weekly.

Research found that 50% of graduate students experiencing mental health issues said they did not agree that their principal investigator functioned as a role model or mentor. Studies show that poor student-supervisor relationships are among the strongest predictors of mental health problems in PhD students.

Some supervisors are actively harmful: dismissive, bullying, exploitative, boundary-violating. Others are simply absent, overwhelmed by their own pressures, or fundamentally unsuited to mentorship.

You picked this supervisor for their research reputation. You’re stuck with their mentorship style—or lack thereof.

What Actually Works

Document Everything

Keep records of

- Scheduled meetings (and cancellations)

- Feedback given

- Agreed-upon goals and timelines

- Problematic interactions

If the relationship deteriorates, documentation protects you.

Seek Alternative Mentorship

Your PI doesn’t have to be your only mentor:

- Co-supervisor or committee members

- Postdocs in your lab

- Faculty in adjacent departments

- Researchers at other institutions in your field

Build a mentorship network. Don’t rely on one person for all guidance and support.

Set Boundaries—Even with PIs

You can (and should) say:

- “I need feedback by [date] to stay on schedule”

- “I can incorporate X and Y suggestions, but Z would require starting over. Can we prioritize?”

- “I’m taking the weekend off for mental health”

Practice these conversations. PIs are human—most respond to clear, professional boundary-setting.

Know When to Escalate

If your supervisor is:

- Verbally abusive

- Sexually harassing you

- Blocking your progress deliberately

- Creating hostile environment

Go to your department chair, graduate program director, or ombudsperson. Document everything first. You have rights.

Consider Switching Supervisors

This isn’t failure. It’s recognizing incompatibility. Many successful PhDs switched supervisors mid-program. The stigma exists, but your mental health and career matter more.

The Emergency Exit

Sometimes the healthiest choice is leaving. PhDs aren’t worth:

- Severe depression requiring hospitalization

- Suicidal ideation

- Complete loss of self-worth

- Permanent damage to mental health

Leaving is hard. It feels like failure. But survival isn’t failure—it’s wisdom.

Research Reference

Studies examining doctoral student wellbeing identify student-supervisor relationship quality as one of the strongest predictors of mental health outcomes, with poor relationships linked to increased depression, anxiety, and dropout rates. Source: https://www.informingscience.org/Publications/4670

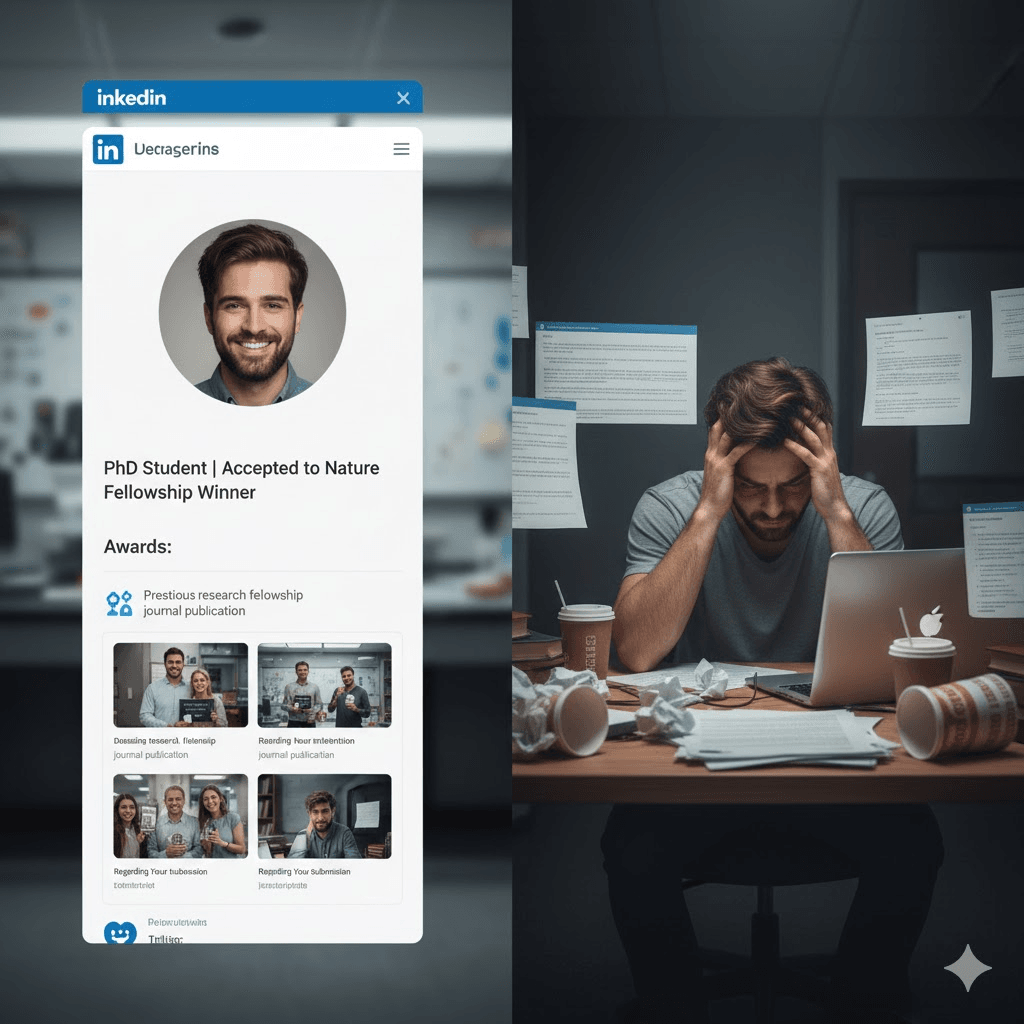

5. “The Comparison Trap: When LinkedIn Becomes a Weapon of Self-Destruction”

You open LinkedIn. Your cohort mate just published in Nature. Another got a postdoc at Stanford. Someone else won a prestigious fellowship.

You? You’re still revising Chapter 2. For the ninth time.

Everyone else seems to be thriving. Winning awards. Presenting at conferences. Building impressive CVs. Meanwhile, you’re struggling to get out of bed.

Social comparison research shows that doctoral students’ imposter syndrome is linked to seeing others as more skilled, underestimating own abilities, dissatisfaction with performance, and feelings of being outside the community. The more you compare, the worse you feel.

But here’s the truth: everyone curates their professional presence. Nobody posts: “Cried in the lab today.” “Submitted to third-choice journal after two rejections.” “PI said my work was ‘disappointing.'”

You’re comparing your behind-the-scenes mess to everyone else’s highlight reel. It’s a losing game designed to make you miserable.

What Actually Works

Curate Your Social Media Diet

- Unfollow or mute accounts that trigger comparison spirals

- Follow accounts that normalize struggle: PhD Comics, academic Twitter honest voices

- Set time limits: 10 minutes daily maximum on academic social media

Recognize Everyone’s Timeline Is Different

That cohort mate with the Nature paper? Maybe they

- Had well-established project when they started

- Work with a supervisor who’s extremely hands-on

- Sacrificed mental health for productivity

- Got lucky with timing

None of which means: “They’re better than you.”

Celebrate Others Without Diminishing Yourself

When someone shares success

- “That’s great news!” (genuine)

- NOT: “I’ll never achieve that” (self-sabotage)

Their success doesn’t erase your potential. Academia isn’t zero-sum.

Focus on Your Own Progress Markers

Create a “Wins” document. Every week, add:

- Skills you’ve developed

- Problems you’ve solved

- Experiments that worked

- Concepts you now understand

Review this monthly. You’re learning constantly—you just don’t notice because you’re focused on what you haven’t achieved yet.

Research Reference

Studies on imposter phenomenon in PhD students found that social comparison, perfectionism, and lack of belonging significantly predict imposter feelings, which mediate the relationship between perceived belongingness and mental health outcomes. Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10734-022-00921-w

The Uncomfortable Truth About PhD Programs

Here’s what your acceptance letter didn’t mention: The system is designed for attrition. Most programs admit more students than they can adequately support, knowing many won’t finish. Research shows that unpredictable working hours, time pressures, fear of failure, and uncertain career paths can lead to high stress, with some studies reporting one-third of PhD students at risk of developing psychiatric disorders.

The culture glorifies suffering. “I worked 90 hours this week” becomes a badge of honor. Taking a mental health day gets side-eyes. Admitting struggle feels like admitting weakness.

Funding structures are exploitative. You’re doing skilled labor—research, teaching, publishing—for poverty wages. Many PhD students qualify for food assistance but don’t apply due to shame.

Mental health support is inadequate. Most universities offer limited counseling sessions, overburdened services, and therapists unfamiliar with academic pressures.

But here’s the other truth: You can survive this. Not by working harder—by working smarter and protecting yourself.

Your Daily Survival Toolkit

Morning Routine (15 minutes)

- 7:00 AM: Wake without immediately checking email

- 7:05 AM: Physical movement (walk, stretch, anything)

- 7:10 AM: Set ONE priority for today (not ten)

- 7:15 AM: Eat breakfast (your brain needs fuel)

During Work Hours

- PI-from-Space perspective exercise when imposter syndrome hits

- Pomodoro breaks (25 work, 5 rest)

- Hydration and real food (not just coffee and anxiety)

- Leave the office/lab at designated time

Evening Wind-Down (20 minutes)

6:00 PM: Work stops (protect this boundary)

- 6:10 PM: Document one win from today

- 6:15 PM: Physical decompression (walk, exercise, shower)

- 6:30 PM: Connect with non-academic humans

Weekly Non-Negotiables

- Small Win Friday thread with lab mates

- One complete day off (Sunday shutdown)

- Social connection outside academia

- One activity purely for joy

Monthly Check-Ins

- Review progress document (see how much you’ve learned)

- Assess supervisor relationship (escalate if needed)

- Mental health inventory (am I okay?)

- Celebrate: you survived another month

When Everything Becomes Too Much

If you’re reading this section, you’re probably in crisis. The paper got rejected again. Your supervisor crushed you in front of others. You’re questioning whether you’ll ever finish. Whether you even want to.

Listen carefully: Your worth is not determined by your PhD. Period.

Research shows that mental health resources are crucial, yet many students don’t access them due to stigma or lack of awareness. If you’re experiencing:

- Persistent hopelessness

- Suicidal thoughts

- Inability to function

- Complete loss of joy in everything

Reach out immediately

Mental Health Resources

Global

- International Association for Suicide Prevention: https://www.iasp.info/resources/Crisis_Centres/

US

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call/text 988 (24/7)

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

UK

- Samaritans: 116 123 (24/7)

- NHS Mental Health Helpline: Call your local number

Australia

- Lifeline: 13 11 14 (24/7)

- Beyond Blue: 1300 224 636

Canada

- Crisis Services Canada: 1-833-456-4566

India

- KIRAN Helpline: 1800-599-0019 (24/7)

- Vandrevala Foundation: +91-9999666555

University Resources

- Student counseling services (usually free)

- Graduate ombudsperson

- Student disability services (mental health qualifies)

Remember

- Your PhD will not love you back

- No publication is worth your life

- Leaving is not failure if staying destroys you

- You are more than your research

A Letter to You, From Someone Who Survived

You’re reading this at 11 PM, aren’t you? After another crushing day. Another rejected draft. Another reminder that you’re “behind.”

I want you to know: You are not behind. You’re exactly where you are, doing impossibly difficult work in a system designed to make you feel inadequate.

Your struggles don’t mean you’re weak. They mean you’re human, attempting something extraordinarily challenging with insufficient support.

That voice telling you you’re not smart enough? It’s lying. You were admitted because qualified people believed in your potential. Imposter syndrome whispers loudest to those who care most about their work.

Your cohort mate’s success doesn’t erase yours. Academia has space for both of you. Their Nature paper doesn’t mean you won’t publish. Their fellowship doesn’t consume yours. There’s enough success to go around—scarcity thinking is the system’s weapon against solidarity.

Your supervisor’s harshness reflects their own pressures, not your inadequacy. Hurt people hurt people. Their criticism says more about them than you.

You deserve

- Supportive mentorship

- Reasonable working hours

- Mental health that doesn’t require crisis intervention

- A career path that doesn’t destroy you

- To be valued as a whole human, not just a research machine

Research shows PhD students face immense pressures, but those who build support networks, set boundaries, practice self-compassion, and seek help when needed not only survive—they often thrive.

Final Reminders: You’re Going to Be Okay

Daily Anchors

- PI-from-Space perspective exercise (5 minutes when spiraling)

- Small Win Friday thread (community over competition)

- Evening shutdown (work ends, life begins)

- One win documented daily

- One moment of kindness to yourself

Weekly Non-Negotiables

- Sunday complete shutdown

- Connection with non-academic humans

- Movement/exercise (your body needs this)

- One joy-bringing activity

Monthly Reality Checks

- Am I okay? (Be honest)

- Is my supervisor relationship healthy?

- Do I need more support?

- Have I made any progress? (You have)

Remember

PhDs are designed to be hard—difficulty doesn’t mean failure

- Everyone feels like an imposter sometimes

- Your research contributes value, even if it feels small

- Taking care of yourself is productive, not selfish

- You are more than your publications

If today feels impossible, just make it to tomorrow. Then do it again. That’s all you need.

One paragraph. One experiment. One breath. One day at a time.

You’re going to be okay.

Research References Cited

- Nature (2019): The mental health of PhD researchers demands urgent attention

- Nature Scientific Reports (2024): Mental health of PhD students in Australia

- ScienceDaily (2018): Depression, anxiety high in graduate students

- ScienceDirect (2024): PhD studies hurt mental health

- Nature (2018): More than one-third of graduate students report depression

- Nature (2021): Depression and anxiety ‘the norm’ for UK PhD students

- Nature (2020): Signs of depression soar among US graduate students

- Nature Biotechnology (2018): Evidence for mental health crisis in graduate education

- Nature Cell Biology (2018): A PhD state of mind

- Springer Nature (2019): Nature PhD survey on mental health and harassment

- PMC (2023): The impostor phenomenon among doctoral students: scoping review

- International Journal of Doctoral Studies (2020): PhD Student Experiences with Impostor Phenomenon in STEM

- ResearchGate (2020): PhD Imposter Syndrome: Antecedents and Consequences

- IJDS (2020): PhD Imposter Syndrome and Doctoral Well-Being

- Higher Education (2022): Too stupid for PhD? Doctoral impostor syndrome Finland

- The Savvy Scientist (2025): Feeling Like a Fraud? PhD Imposter Syndrome

- PhD Academy (2024): PhD impostor syndrome guide

- South Coast DTP (2025): Overcoming Imposter Syndrome as PhD Student

- ResearchGate (2020): PhD Student Experiences with Impostor Phenomenon

- Student News Manchester (2024): PhD Diaries: Imposter syndrome first year