Perfect pitch got you in the door; it won’t stop the panic attacks, tendonitis, or the day the concerto you love finally makes you numb. Talent is just the entrance fee.

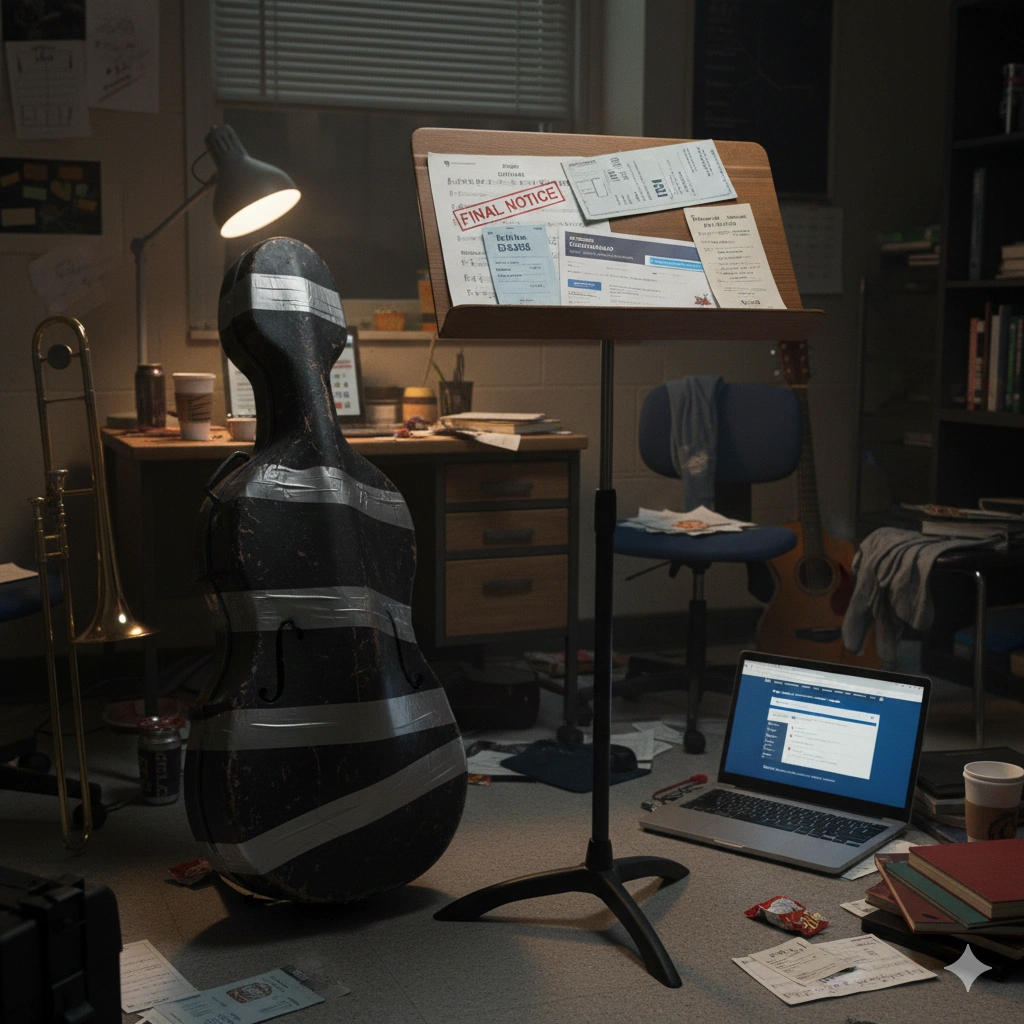

It’s 11 PM, and you’re still in the practice room. Your wrists are throbbing, your shoulders burning, but you can’t leave—not yet. That audition is in three days, and the passage in measure 47 still isn’t flawless. Your teacher’s voice echoes: “Perfection isn’t a goal, it’s the baseline.” Meanwhile, your hands have begun to betray you with sharp, stabbing pains that shoot through your tendons every time you attempt that particular arpeggio.

You’re not just dealing with challenging repertoire. You’re navigating performance anxiety that makes your heart race and palms sweat before every recital, perfectionism that whispers you’ll never be good enough, and now, tendonitis from over-practicing—the physical manifestation of pushing your body beyond its limits in pursuit of an impossible standard.

Welcome to the hidden crisis of music education and professional musicianship. While conservatories celebrate technical mastery and artistic excellence, they rarely address the mental and physical toll exacted from the students sacrificing everything for their craft. The Music Teachers National Association recognizes that psychological health, particularly surrounding public performance, involves numerous social and emotional factors that represent both the essence of music’s importance and a significant source of student stress.

Research examining musicians’ health reveals that between 73.4% and 87.7% of musicians experience work-related musculoskeletal disorders, while performance anxiety affects between 16.5% and 60% of professional musicians and 21% to 50% of students. For those still in training, these rates climb to 33% in adolescent musicians.

This isn’t about weakness in a demanding field. This is about a pedagogical system that systematically breaks down the very artists it claims to develop.

The Five Daily Battles You’re Fighting Behind Practice Room Doors

1. The Perfectionism Paradox: When “Good Enough” Doesn’t Exist in Your Vocabulary

The Reality

You spent six hours perfecting a three-minute piece. It still doesn’t sound right. Every note must be flawless, every interpretation pristine, every performance transcendent. Anything less feels like failure. Your teacher demands excellence. Your peers seem effortlessly brilliant. Meanwhile, you’re drowning in the gap between your current ability and your impossible standards.

Picture This

A conservatory pianist sits alone at 2 AM, replaying a recording of her jury performance. She played beautifully—the faculty said so. But she hears every imperfection: the slight hesitation in measure 23, the tone that wasn’t quite crystalline in the development section. She convinces herself she failed. Tomorrow, she’ll practice eight hours to “fix” problems no one else noticed.

Research examining the relationship between perfectionism and music performance anxiety reveals a consistently strong, positive, and highly significant correlation from ages 10 through 17, particularly regarding concern over mistakes. Females experience a steeper and more intense developmental trajectory than males, and both MPA and perfectionism levels increase with years of musical experience.

Research Backing

Studies indicate that perfectionism is characterized by persistent striving for flawlessness, elevated self-criticism, and establishment of unrealistically high standards. Musicians with perfectionistic tendencies ruminate persistently on potential mistakes, heightening fear of failure and intensifying concerns about perceived judgment and criticism.

Mindful Solutions

- Redefine “Practice Perfect”: Excellence isn’t eliminating all mistakes; it’s creating compelling music despite human imperfection. Record yourself performing and listen for musicality, not just technical accuracy

- Set Process Goals, Not Outcome Goals: Instead of “play this piece perfectly,” try “explore three different interpretive approaches” or “improve breath control in challenging phrases”

- Practice Self-Compassion: When you notice perfectionistic thoughts, pause. Ask: “Would I say this to a fellow musician I care about?” Treat yourself with the same kindness

- Track Progress, Not Perfection: Keep a practice journal noting improvements and breakthroughs, however small. Progress isn’t linear, and documenting growth helps combat perfectionism’s tunnel vision

2. Performance Anxiety: The Stage Fright That Never Actually Goes Away

The Reality

Your stomach churns, palms sweat, heart races. You know this piece by memory—you’ve played it flawlessly dozens of times. But the moment you step onstage, your mind goes blank, your fingers feel disconnected from your body, and suddenly you’re not a musician anymore—you’re just someone trying desperately not to collapse under scrutiny.

Picture This

A violinist stands backstage at a competition, listening to the competitor before her deliver a stunning performance. Her hands are trembling. She’s practiced six months for this ten-minute audition. Her entire scholarship, her future opportunities, her validation as a musician—everything hinges on the next few minutes. The fear isn’t motivating. It’s paralyzing.

Music Performance Anxiety manifests physiologically through increased heart rate and sweaty palms, psychologically through negative self-talk and catastrophizing, and behaviorally through avoidance or elaborate preparation rituals. Although MPA isn’t consistently associated with poor performance outcomes, the fear of making mistakes drives many musicians to strive for perfection, creating a vicious cycle.

Research Backing

MPA is characterized by persistent distress and apprehension about public performance skills, with symptoms that can become so aversive that despite forcing oneself to endure performance, it becomes intolerable. According to the World Health Organization, persons suffering severe MPA face significant mental health consequences.

Mindful Solutions

- Normalize the Physiology: Your racing heart and sweaty palms aren’t signs of failure—they’re your body preparing for a high-stakes activity. Reframe arousal as readiness, not weakness

- Simulate Performance Conditions: Practice performing for small audiences (friends, fellow students) regularly. Exposure reduces anxiety’s power over time

- Develop Pre-Performance Rituals: Create consistent routines that signal to your nervous system: “I’ve done this before, I can do it again.” Physical warm-ups, mental visualization, specific breathing exercises

- Focus Externally, Not Internally: During performance, direct attention to the music itself—the story you’re telling, the emotional journey—rather than monitoring your anxiety or potential mistakes

3. Tendonitis and Physical Pain: When Your Body Says “No More”

The Reality

Your wrists ache constantly. Sometimes it’s a dull throb; other times, sharp pains shoot through your forearms. You’ve tried icing, heating, wrapping. Nothing helps. But you can’t stop practicing—the recital is next week, the competition in two months. Everyone says “no pain, no gain.” But this pain isn’t productive. It’s destructive.

Picture This

A guitarist wakes up unable to fully extend her fingers. The stiffness has progressed from mild discomfort to genuine dysfunction. She has a master class in three hours. She takes ibuprofen, wraps her wrist, and heads to the practice room anyway. She’s terrified—not of the pain, but of falling behind, losing her competitive edge, disappointing her teacher. The pain is her body screaming for rest. She ignores it.

Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders affect between 73.4% and 87.7% of musicians, with string players experiencing the highest prevalence. Common conditions include overuse syndrome, tendonitis, tenosynovitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and cubital tunnel syndrome. These injuries result from repetitive precise movements in prolonged non-ergonomic postures.

Research Backing

Overuse syndrome is the most common cause of upper extremity symptoms related to playing. Repetitive movements combined with increased muscle activity that stabilizes the wrist, elbow, and shoulder girdle load stress on surrounding tendons, leading to chronic tendinopathy over time. Prolonged static postures with elevated or laterally fixed shoulders result in muscle imbalance and chronic myofascial pain.

Mindful Solutions

- Implement the 30-5 Rule: Take a mandatory 5-minute break every 30 minutes of practice. Stretch, hydrate, release tension. Productivity isn’t measured by hours logged but by quality practice achieved

- Practice Mindful Repetition: Have specific goals for each repetition. Mindless repetition increases injury risk without improving performance

- Warm Up and Cool Down: Treat practice like athletic training—gentle stretches before, progressive warm-up exercises, cool-down stretches after

- Seek Professional Help Early: Don’t wait until pain becomes debilitating. Physical therapists, occupational therapists, and performing arts medicine specialists can address issues before they become career-threatening

4. Comparison Culture: When Everyone Else Seems Better Than You

The Reality

You scroll through social media seeing peers posting about competition wins, conservatory acceptances, masterclass selections. Everyone seems to be thriving while you’re struggling just to maintain technique. In ensemble rehearsals, you hear others nail passages you’ve practiced for weeks. Your teacher casually mentions another student’s progress. The message feels clear: you’re not measuring up.

Picture This

A composition student attends a peer’s premiere. The piece is brilliant—innovative, emotionally resonant, technically sophisticated. Instead of feeling inspired, he feels crushed. His own compositions suddenly seem derivative, unsophisticated, worthless. He goes home and deletes weeks of work. If he can’t be the best, why bother at all?

The traditional classical music education system often expects students to uphold high levels of perfectionism, engage in excessive rehearsal, and utilize recordings as models of perfection, without attending to emotional needs or preparing them for performance realities. High levels of MPA among musicians often start in academic centers where teachers work without considering students’ dual physical and psychic dimensions.

Research Backing

Early exposure to assessments in highly competitive settings serves as an environmental risk factor increasing vulnerability to MPA. The competitive nature of music education creates environments where musicians are reluctant to admit injuries or struggles, often presenting late for treatment when conditions have already become severe.

Mindful Solutions

Curate Your Exposure

If social media comparisons trigger inadequacy, limit exposure. Your mental health matters more than staying current on peers’ achievements

- Recognize Highlight Reels vs. Reality: Everyone posts wins, not struggles. That peer’s competition success doesn’t show the hours of rejected applications, failed auditions, and self-doubt

- Define Success Personally: What does musical fulfillment look like for you specifically? Not your teacher, not your parents, not your peers—you. Build toward that definition, not someone else’s

- Celebrate Others’ Success Genuinely: When you can authentically feel joy for peers’ achievements, you short-circuit the comparison trap. Their success doesn’t diminish your potential

5. Financial Pressure: When Passion Meets Poverty

The Reality

Your student loans are mounting. You work three part-time jobs on top of full course loads and practice requirements. Private lessons, instrument maintenance, competition fees, summer programs—everything costs money you don’t have. Your peers seem financially comfortable, affording opportunities you can’t. Meanwhile, everyone says “pursue your passion,” but passion doesn’t pay rent.

Picture This

A conservatory vocal student receives an invitation to a prestigious summer program—her dream opportunity with faculty who could transform her career. The program costs $5,000. Her family can’t help. Student loans won’t cover summer programs. She could take out private loans, but she’s already $80,000 in debt with uncertain career prospects. She declines the invitation and watches her financially secure classmates attend. The opportunity gap isn’t about talent. It’s about access.

Musicians face significant financial challenges throughout training and professional careers. The cost of instruments, private instruction, masterclasses, competitions, and academic programs creates substantial barriers. Combined with uncertain job prospects and gig-economy realities post-graduation, financial stress becomes a constant companion to artistic development.

Research Backing

Research examining stress in music students indicates that financial pressures compound other stressors, creating cycles of overwork as students attempt to balance earning money with maintaining practice standards and academic requirements. This often leads to physical injury, mental health decline, and ultimately, burnout.

Mindful Solutions

- Research Hidden Resources: Many institutions have emergency funds, diversity scholarships, or hardship grants that aren’t widely advertised. Meet with financial aid counselors specifically to explore options

- Build Community Support: Form equipment-sharing arrangements with fellow students, create carpooling systems for auditions, establish peer-teaching exchanges to reduce private lesson costs

- Reframe Financial Limitations as Creative Constraints: Some of music history’s most innovative work emerged from resource scarcity. Limited access to specific programs doesn’t limit your potential for artistic growth

- Develop Multiple Income Streams: Teaching, accompanying, arranging, online content creation—diversify how you engage with music professionally

Quick Mindfulness Practices: Your 60-300 Second Survival Toolkit

Practice 1: The 4-Minute “Scale Slowdown” (When Practice Becomes Obsessive)

When to Use

During marathon practice sessions, when you’ve lost track of time, when physical pain emerges, or when you’re repeating passages mindlessly without improvement

How

Minute 1—Physical Awareness: Stop playing. Stand or sit in neutral position. Scan your body from head to toes. Where do you feel tension? Where do you feel pain? Don’t judge, just notice

- Minute 2—Breath Regulation: Place one hand on your belly. Breathe in through your nose for 4 counts, feeling your abdomen expand. Hold for 2 counts. Exhale through your mouth for 6 counts. Repeat three times

- Minute 3—Intention Setting: Ask yourself three questions:

- What am I actually trying to accomplish right now?

- Am I making meaningful progress, or just going through motions?

- What would compassionate practice look like for the next 15 minutes?

- Minute 4—Gentle Movement: Roll your shoulders back 5 times. Gently stretch your wrists, flexing and extending. Shake out your hands. When you return to your instrument, start with something you love playing, not what you’re struggling with

Science Behind It

This practice interrupts compulsive practice patterns, reduces cortisol levels, activates the parasympathetic nervous system, and reengages prefrontal cortex function for more conscious, effective practice.

Practice 2: The 2-Minute “Note Gratitude” (When Self-Criticism Spirals)

When to Use

After disappointing performances, during intense comparison moments, when perfectionism feels overwhelming, or before high-pressure auditions/performances

How

- 0-30 Seconds—Grounding: Place both feet flat on the floor. Press down gently. Say internally or aloud: “I am here. I am enough. I am a musician.”

- 30-90 Seconds—Gratitude Inventory: Name three specific musical moments you’re grateful for:

- One technical skill you’ve developed (even if it’s not perfect)

- One piece of music that moves you

- One person who supported your musical journey

- 90-120 Seconds—Reframe and Release: Identify one critical thought you’ve been carrying. Now reframe it:

- Critical thought: “I’ll never be as good as [peer name]”

- Reframe: “My musical voice is unique. Comparison doesn’t serve my growth.” Take one deep breath and consciously release the critical thought on the exhale

Science Behind It

Gratitude practices activate reward circuits in the brain, increase dopamine and serotonin, reduce amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli, and strengthen neural pathways associated with positive self-perception.

What Actually Helps: Evidence-Based Strategies for Musicians

Institutional Support That Works

The Music Teachers National Association recognizes that music teachers serve as primary channels for changing how music is taught and played. In efforts to reduce performance injuries and encourage good auditory, physical, and emotional health, teachers must become substantially involved in injury prevention by teaching health-conscious music-related practices.

Action Steps

- Advocate for curricular integration of musician wellness topics—not as optional workshops but as required coursework

- Request that your institution provide access to performing arts medicine specialists, sports psychologists, and physical therapists who understand musicians’ unique needs

- Establish peer support groups where students can discuss performance anxiety, physical pain, and mental health challenges without judgment or competitive pressure

- Push for policy changes around practice hour requirements—quality over quantity, with mandatory rest periods

Therapeutic Interventions That Reduce MPA

Research reviewing interventions for music performance anxiety identifies several evidence-based approaches: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, music therapy, yoga and mindfulness practices, virtual reality exposure, hypnotherapy, biofeedback, and multimodal therapy. Most reviewed studies demonstrated encouraging improvements in musicians’ MPA following delivered interventions.

Practical Implementation

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Work with therapists to identify and restructure catastrophic thinking patterns surrounding performance

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Learn to accept anxiety as present without letting it control behavior. ACT shows notable improvements in psychological flexibility

- Mindfulness and Yoga: Regular practices significantly reduce anxiety and enhance psychological resilience while mitigating physical symptoms

- Performance Simulation with Biofeedback: Use technology to monitor physiological responses during simulated performances, learning to regulate arousal states

Physical Health Protocols

Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders are comparable to vocation-related disorders in other professions. Prevention requires proactive approaches rather than reactive treatment of already-established injuries.

How to Implement

- Structured Practice Schedules: The University of Michigan School of Music recommends 5-minute breaks every 30 minutes, micro-breaks to notice and release tension, and mindful repetition with specific goals for each repetition

- Cross-Training: Engage in cardiovascular training, strengthening, and stretching separate from musical practice. Your body needs balanced development

- Early Intervention: Address pain immediately—not after it becomes debilitating. Connect with health providers, wellness programs, or sports medicine clinics

- Mind-Body Practices: Participate in Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais Method, or yoga classes specifically designed for performing artists

Breaking the Silence: When to Seek Professional Support

Musicians are often reluctant to admit injuries or struggles due to the competitive nature of the field, frequently presenting late when conditions have become severe or career-threatening. This silence perpetuates a culture where suffering is normalized rather than addressed.

Red Flags Requiring Immediate Professional Support

- Physical pain that doesn’t resolve with rest or actively worsens

- Panic attacks before performances

- Persistent thoughts that you should quit music entirely

- Depression interfering with daily functioning

- Self-harm thoughts or behaviors

- Complete loss of joy in music-making

How to Access Help

- Campus Counseling Services: Most conservatories and universities offer free or low-cost mental health support

- Performing Arts Medicine Clinics: Specialized centers understand musicians’ unique physical and psychological needs

- Music Teachers National Association Resources: MTNA provides wellness resources specifically for musicians at mtna.org/wellness

- Athletes and the Arts Initiative: Recognizes performing artists as athletes requiring similar wellness support systems

Your Path Forward: Sustainable Musicianship, Not Sacrificial Artistry

Music education romanticizes suffering for your art. We celebrate musicians who “gave everything” to their craft, who practiced until their fingers bled, who pushed through pain to achieve perfection. But here’s the truth nobody wants to admit: burnout doesn’t make better musicians. Injury doesn’t create more expressive performances. Sacrificing your mental and physical health doesn’t serve your musicianship—it destroys it.

You don’t need to choose between artistic excellence and well-being. That’s a false dichotomy perpetuated by an educational system that hasn’t adequately addressed the mental and physical health needs of its students. The goal isn’t eliminating performance anxiety or physical challenge—music-making is inherently demanding—but developing tools that help you navigate pressure without self-destruction.

Your unique musical voice, your interpretive insights, your artistic passion—these are what the world needs. But they only matter if you’re still here to share them. A sustainable music career means you’re still making music you love in ten, twenty, thirty years, not burning out brilliantly during your twenties and disappearing.

Remember: Your worth isn’t determined by competition placements, audition results, or faculty approval. You are not your performance anxiety. You are not your physical limitations. You are not your perfectionism. You are a human being who happens to make music—and that humanity deserves protection, compassion, and care.

Take what resonates from this article. Implement what feels possible. Your journey is yours alone, but you’re not walking it alone. Thousands of musicians are navigating similar struggles, finding their own balance, building their own support systems, and redefining what it means to succeed sustainably in music.

Your perfect pitch won’t save you from burnout. But you can save yourself.

Resources for Continued Support

- Music Teachers National Association (MTNA): mtna.org/wellness – Comprehensive wellness resources

- Athletes and the Arts Initiative: Wellness programs for performing artists

- Performing Arts Medicine Association (PAMA): Specialized healthcare providers

- Mindful Engineer Resources: Stress & Burnout Practices

- Guided Mindfulness Practices: Meditation for Musicians

Reference Study

- Music Teachers National Association. (2023). Wellness Resources for Musicians. https://www.mtna.org/MTNA/Learn/Wellness_Resouces/Musician_Wellness.aspx

- University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre & Dance. (2024). Wellness Guides. https://smtd.umich.edu/backstage/wellness/education/wellness-guides/

- Athletes and the Arts Initiative. Multi-organizational wellness for performing artists. https://athletesandthearts.com/

- Fernández-Rodríguez, R., et al. (2023). Current trends in music performance anxiety intervention. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10525579/

- Simoens, V. L., & Tervaniemi, M. (2023). It’s not a virus! Reconceptualizing and de-pathologizing music performance anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1194873/full

- Aubry, L., & Küssner, M. B. (2025). Early harmonies, enduring echoes—how early life experiences and personality traits shape music performance anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1360011/full

- Dobos, B., Piko, B. F., & Kenny, D. T. (2019). Music performance anxiety and its relationship with social phobia and dimensions of perfectionism. SAGE Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1321103X18804295

- Ryan, C., Andrews, N., & Tsang, J. (2025). Music performance anxiety and perfectionism: A comparison of in-person and virtual contexts. SAGE Journals. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10298649241297229

- Patston, T., & Osborne, M. S. (2015). The developmental features of music performance anxiety and perfectionism in school age music students. ScienceDirect. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2211266915000596

- Biskanaki, F., et al. (2025). Therapeutic interventions for music performance anxiety: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/15/2/138

- Steinmetz, A., et al. (2015). Musicians’ medicine: Musculoskeletal problems in string players. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3758983/

- Baadjou, V., et al. (2019). Musculoskeletal disorders and complaints in professional musicians: A systematic review. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00420-019-01467-8

- Zhang, H., et al. (2024). Subjective experiences of tertiary student pianists with playing-related musculoskeletal disorder. PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11075168/

- Musicians and Repetitive Strain Injuries: How to Practice Hard and Stay Healthy. Disc Makers Blog. https://blog.discmakers.com/2012/04/musicians-and-repetitive-strain-injuries-rsi-how-to-practice-hard-and-stay-healthy-2/

- RSI (Repetitive Strain Injury). CPD for General Practitioners. https://gpcpd.heiw.wales/clinical/health-problems-of-musicians/rsi-repetitive-strain-injury/