Your complete guide to understanding the 9 dimensions of flow—and finally accessing that elusive state where work feels like play

You know that feeling when you’re so absorbed in something that three hours pass like three minutes? When your fingers are flying across the keyboard or your brush is moving across the canvas, and you’re not really “thinking” anymore—you’re just… doing?

And then your phone buzzes, or someone asks you a question, and suddenly you’re yanked out of that magical state, and you can’t figure out how to get back in?

Yeah, that feeling. That’s flow. And it’s not magic, mystical, or reserved for artists and athletes. It’s a well-documented psychological state that you can understand, cultivate, and access way more often than you currently do.

Let me show you how.

What Flow Actually Is (According to the Guy Who Named It)

Flow was first described by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (pronounced “cheeks-sent-me-high”—I know, I had to practice it too) in 1975. He was a psychologist who got curious about what made people truly happy, not just comfortable or content, but deeply satisfied with life.

So he did what any reasonable researcher would do: he studied people who were really, really good at what they did. Artists, surgeons, rock climbers, chess players, dancers. He asked them to describe moments when they were at their best.

And they all described the same thing. A state where:

- Time disappeared

- Self-consciousness vanished

- The task and the person doing it merged into one

- The work felt effortless yet deeply engaging

- Nothing else mattered

Csíkszentmihályi called this “flow” because people kept describing it like being carried by a current. You’re not fighting or forcing. You’re riding.

Later, in his 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, he broke down exactly what makes this state tick. Not in a vague “follow your passion” way, but in a precise, replicable, “here are the actual components” way.

And then Martin Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, picked it up in 2011 and said essentially: “Hey, this flow thing? This is one of the five core elements of human wellbeing. Not just nice to have. Essential.”

“I thought flow was something plumbers fixed. Turns out it’s something psychologists study and the rest of us desperately try to recreate every time we sit down to work.”

The 9 Dimensions of Flow (AKA: The Checklist You’ve Been Missing)

Here’s where it gets practical. Csíkszentmihályi identified nine specific characteristics that define the flow state. Think of these as both a diagnostic tool (“am I in flow right now?”) and a recipe (“how do I create the conditions for flow?”).

Let’s break them down.

1. Challenge-Skill Balance: The Goldilocks Zone

This is the foundation. Flow happens when the challenge of the task matches your skill level almost perfectly.

Too easy? You’re bored. You’re scrolling Twitter while “working.” You’re phoning it in.

Too hard? You’re anxious. You’re paralyzed. You’re Googling “how to do [thing]” for the seventeenth time and considering a career change.

Just right? You’re stretched but not breaking. You’re learning but not drowning. You’re engaged.

Real-world example:

I’m a decent writer. If you ask me to write a grocery list, I’m bored. If you ask me to write a novel in ancient Greek, I’m screwed. If you ask me to write an article on a topic I know well but need to research and synthesize? That’s the sweet spot. I’ll lose track of time.

How to use this:

Look at your current project. Rate your skill level 1-10. Rate the challenge level 1-10. If they’re more than 2 points apart, you’re probably not going to hit flow.

- If you’re bored (skill > challenge), make it harder. Add constraints. Set a tighter deadline. Raise the quality bar.

- If you’re anxious (challenge > skill), break it down. Start with the part you can do. Build skill in small chunks. Ask for help.

For more on matching challenge to skill in your work, check out The Art of Calibrating Difficulty: Finding Your Growth Edge.

“My skill level with Excel: 6/10. My boss’s idea of ‘a simple spreadsheet’: requires 47 nested formulas and a minor in applied mathematics. Flow state: not found.”

2. Clear Goals: Knowing Exactly What You’re Aiming For

You can’t hit flow if you don’t know what you’re trying to do. Vague goals create vague effort. Specific goals create focused attention.

This doesn’t mean you need a detailed project plan. It means that at any given moment, you know what “done” looks like for the next 15 minutes.

Not: “Work on the presentation.” But: “Write the opening slide with the main problem statement.”

Not: “Practice piano.” But: “Play this 8-bar section until I can do it smoothly three times in a row.”

The trick: Break big projects into micro-goals. Each one should be completable in one flow session (roughly 90-120 minutes max). Each one should have a clear endpoint.

How to practice this:

Before you start any work session, write down: “By the end of this session, I will have [specific, measurable outcome].” If you can’t write it, you’re not ready to begin.

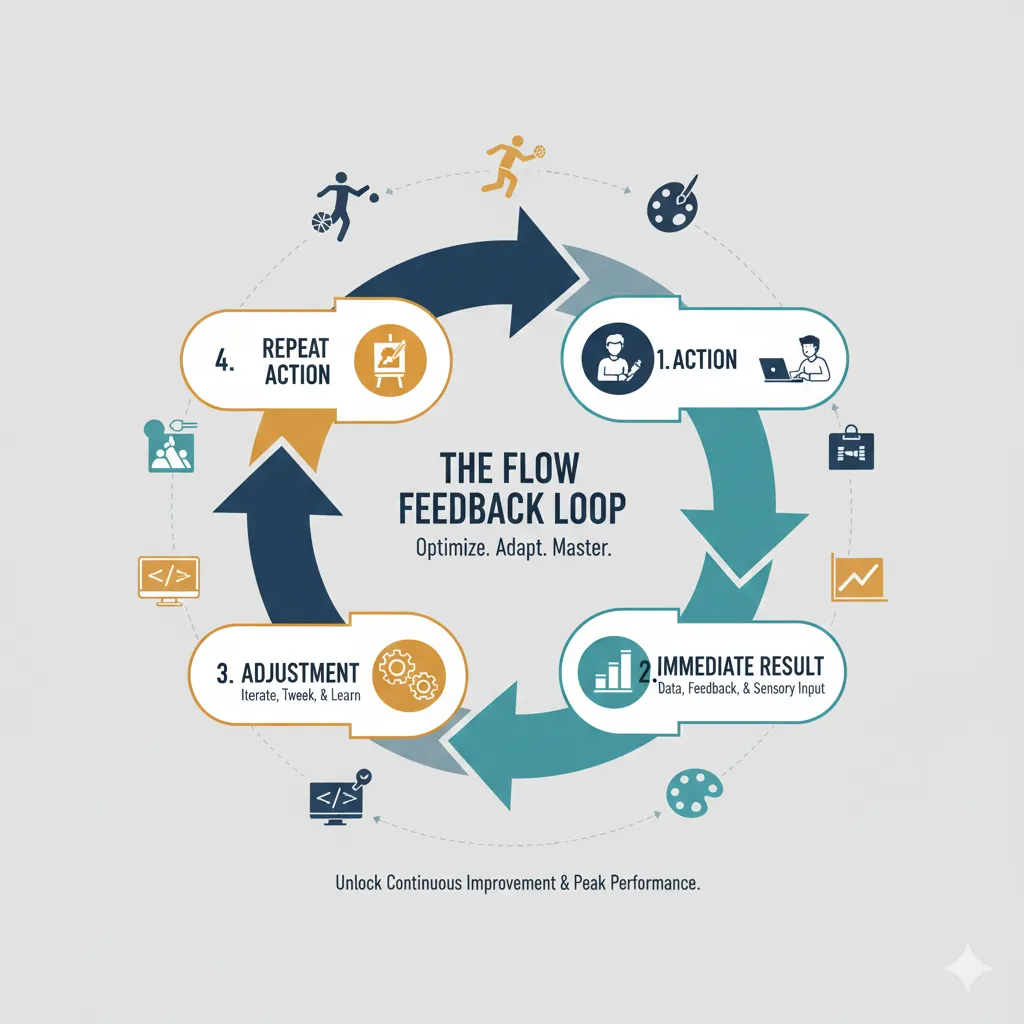

3. Immediate Feedback: Knowing Instantly If You’re On Track

Flow requires a tight feedback loop. You need to know, moment by moment, whether you’re succeeding or failing.

This is why video games are flow machines. You shoot the enemy, it dies. You jump the gap, you make it. You solve the puzzle, it unlocks. Instant feedback.

Real work is often messier. You write a paragraph—is it good? You design a component—will it work? You send an email—did it land?

The solution: Create artificial feedback loops.

- Coders: Write tests first, so you immediately see pass/fail.

- Writers: Read each paragraph aloud. Does it flow? That’s your feedback.

- Designers: Set up a checklist of design principles. Does this meet them? Check, check, check.

- Anyone: Use a timer and track your focus score (how many times did you get distracted in 25 minutes?).

The feedback doesn’t have to be perfect or external. It just has to be immediate and informative.

“The best feedback I ever got was from my code. It literally told me ‘Error on line 47, you absolute walnut.’ Cannot argue with that level of clarity.”

4. Concentration on the Task at Hand: Single-Pointed Focus

Flow requires undivided attention. Not “mostly focused.” Not “focused except for these twelve tabs and this podcast in the background.” Fully. Present.

This is increasingly hard in our notification-drunk world. Every ping is a potential flow-killer.

The research is brutal: It takes an average of 23 minutes to fully return to a task after an interruption (Gloria Mark, UC Irvine). That means if you’re interrupted every 20 minutes, you literally never reach deep focus.

How to protect your focus:

- Phone in another room. Not on silent. Not face-down. In another room. You’ll survive.

- Batch communications. Check email/Slack at set times (10am, 2pm, 4pm). Otherwise, close them.

- Browser extensions. Block distracting sites during work hours. Future you will thank past you.

- Headphones + music or silence. Signal to your brain and others that you’re unavailable.

- Time blocks. Schedule 90-minute focus blocks on your calendar like meetings with your future successful self.

The multitasking myth: You cannot multitask your way into flow. You can only context-switch your way out of it. One task. That’s it.

For a complete guide to eliminating distractions and building focus, see The Mindful Engineer’s Guide to Deep Work.

5. Merging of Action and Awareness: No Gap Between Doing and Being

In flow, there’s no little voice in your head narrating what you’re doing or judging how you’re doing it. You are the action.

The dancer doesn’t think “now I’ll move my left foot, then rotate my hips”—they are the dance.

The surgeon doesn’t think “I’m good at this” or “what if I mess up”—they are the procedure.

You’re not performing the task. You’ve become it.

This is the opposite of our default mode, where we’re constantly commenting on our own experience: “Am I doing this right? How do I look? Is this taking too long? Should I be better at this by now?”

How to practice merging:

You can’t force this, but you can create conditions that invite it:

- Start with clear goals (dimension 2)

- Get immediate feedback (dimension 3)

- Focus completely (dimension 4)

- Stay in the challenge-skill sweet spot (dimension 1)

When those line up, the merging happens naturally. The self-consciousness falls away because there’s no bandwidth left for it. You’re too busy doing the thing to think about doing the thing.

“My therapist calls it ‘getting out of your head.’ My yoga teacher calls it ‘presence.’ My gaming friends call it ‘being in the zone.’ Psychologists call it ‘merging action and awareness.’ I call it ‘that rare moment when my brain shuts up and lets me work.'”

6. Sense of Control: Feeling Capable Even in Uncertainty

In flow, you feel in control—not of the outcome necessarily, but of your ability to handle whatever comes up.

The rock climber doesn’t know if they’ll summit, but they trust their ability to make the next move. The jazz musician doesn’t know where the solo is going, but they trust they can respond to whatever the other musicians play.

This isn’t about confidence or bravado. It’s about a quiet sense of “I’ve got this” that comes from being properly matched to the challenge.

What undermines this:

- Unclear expectations (“I think my boss wants X, but maybe Y?”)

- Missing tools or resources (“I can’t do this without access to…”)

- Skill gaps you’re ignoring (“I should probably learn this first, but…”)

How to build it:

- Prepare. Before complex tasks, do a quick readiness check: Do I have what I need? Do I know what I’m doing? If not, what’s the smallest step I can take?

- Build skill systematically. Control comes from competence. Practice deliberately.

- Start with what you can control. If the project feels overwhelming, identify the piece that’s fully in your control and start there.

7. Loss of Self-Consciousness: The Ego Takes a Nap

In flow, you stop worrying about how you look, what people think, whether you’re good enough. The self-critic goes offline.

This is huge, because for most of us, self-consciousness is the thing that keeps us from taking creative risks or pushing our limits.

In flow, you’re not performing for an audience (even an imaginary one). You’re not protecting your ego. You’re just doing the thing.

Why this matters for creativity:

Self-consciousness is the enemy of flow, and flow is the friend of creativity. When you’re worried about looking stupid, you play it safe. When you’re in flow, you experiment. You try the weird idea. You take the risk.

How to reduce self-consciousness:

- Private practice. Do your exploratory work alone first. Save the performance for when you’ve built momentum.

- Lower the stakes. Call it a draft, a sketch, a prototype. Give yourself permission to suck.

- Focus on process, not product. “Am I engaging fully with this task?” matters more than “Is this going to be amazing?”

8. Distortion of Time: The Clock Becomes Irrelevant

This is the one everyone notices. Hours feel like minutes. Or sometimes, seconds feel like hours (like when athletes describe a play in “slow motion”).

Your subjective experience of time decouples from clock time because you’re not checking the clock. You’re not thinking about time. You’re outside of time.

Why this happens:

When you’re fully absorbed, your brain isn’t tracking time the way it normally does. Normally, your brain is constantly referencing the past (memory) and future (plans), which creates your sense of time passing. In flow, you’re purely present, so time gets weird.

Practical note:

This is why you need to set timers or alarms if you have other commitments. Flow doesn’t care that you have a meeting at 3pm. You’ll look up and it’ll be 3:47.

“I started writing at 9am. Next thing I know, it’s 2pm, I’m starving, my coffee is ice-cold, and I’ve apparently written 3,000 words. Flow is a time machine, and I’m not entirely sure it’s legal.”

9. Autotelic Experience: The Activity Is Rewarding in Itself

“Autotelic” comes from Greek: auto (self) + telos (goal). The activity is its own goal. You’re not doing it for external rewards—money, recognition, grades. You’re doing it because the doing itself is satisfying.

This is the difference between:

- “I’m coding because I need to finish this feature” (extrinsic)

- “I’m coding because watching this thing come to life is genuinely satisfying” (intrinsic/autotelic)

Why this dimension matters most:

If you’re only doing something for external rewards, you’re always trying to get to the end. You’re not present with the process. And flow lives in the process.

The activities that most reliably produce flow are the ones where you can find the intrinsic satisfaction, not just the payoff.

How to cultivate this:

- Notice what you enjoy about the work itself. The craftsmanship. The problem-solving. The learning. The flow of creation.

- Celebrate micro-wins. Each small completion is worth acknowledging: “I solved that piece. Nice.”

- Reframe obligation as opportunity. Instead of “I have to do this,” try “I get to practice this skill.”

For deeper exploration of finding intrinsic motivation in your work, visit Cultivating Intrinsic Motivation: Beyond Carrots and Sticks.

The Flow Equation: Putting It All Together

Here’s the simple truth that Csíkszentmihályi discovered:

Flow = (Clear Goals + Immediate Feedback + Challenge-Skill Match) × (Deep Focus + Loss of Self) = Timeless Absorption + Intrinsic Reward

All nine dimensions work together. You can’t have some of them and call it flow. You need the whole constellation.

But here’s the good news: you don’t have to optimize all nine at once. Start with the big three:

- Match your skill to the challenge (dimension 1)

- Eliminate multitasking and distractions (dimension 4)

- Celebrate small wins to build intrinsic motivation (dimension 9)

Get those right, and the other dimensions tend to fall into place.

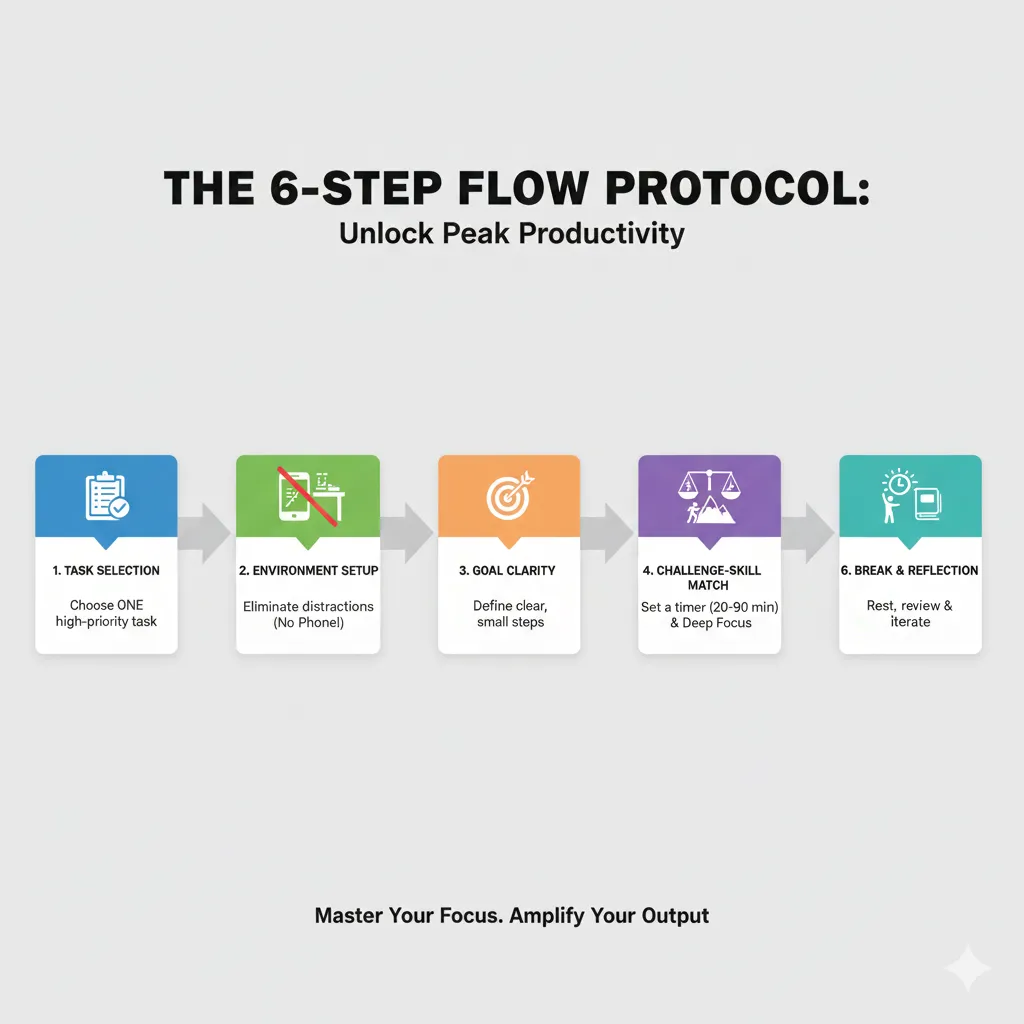

The Practical Protocol: How to Engineer Flow in Your Day

Let’s make this concrete. Here’s a simple protocol you can use starting today.

Step 1: Pick Your Flow Task (5 minutes)

Not every task is flow-worthy. Some things (answering emails, attending meetings, filling out forms) are maintenance work. That’s fine. Don’t force it.

Pick one task that:

- Matters to you

- Challenges you appropriately (not too hard, not too easy)

- Can be done in a 60-120 minute block

- Has a clear endpoint

Write it down: “Today’s flow task: __________”

Step 2: Set Up Your Environment (10 minutes)

Eliminate distractions:

- Phone in another room or drawer

- Close all unrelated browser tabs and apps

- Put on headphones (music or silence—your choice)

- Set your Slack/Teams to “Do Not Disturb”

- Put a sign on your door or your calendar that says “Deep Work: Back at [time]”

Gather what you need:

- Reference materials

- Tools/software

- Water/coffee

- Snack if you’re hungry (nothing worse than hitting flow and then being yanked out by your stomach growling)

Set a timer: 90 minutes is ideal. Don’t go longer—your brain needs breaks.

Step 3: Clarify Your Goal (2 minutes)

Write down exactly what “done” looks like for this session.

Not: “Work on project.” But: “Complete the first draft of section 3, approximately 800 words.”

Not: “Practice coding.” But: “Build the user authentication function and get all tests passing.”

Be specific enough that you’ll know when you’ve crossed the finish line.

Step 4: Check Your Challenge-Skill Ratio (1 minute)

Quick gut check:

- Does this feel too easy? Add a constraint or raise the bar.

- Does this feel too hard? Break it into smaller pieces or lower the bar.

- Does this feel just right—challenging but doable? Go.

Step 5: Start and Stay (90 minutes)

Here’s where the magic happens. Or doesn’t—some days are easier than others.

For the first 10-15 minutes:

- Your brain will resist. This is normal.

- You’ll think of seventeen other things you “should” be doing. Write them on a “later” list and return to task.

- You’ll feel fidgety, uncomfortable, bored. Push through. Flow usually kicks in after this initial resistance.

Once you’re in:

- Keep going until the timer rings or you reach your goal

- If you get stuck, use immediate feedback: “Is this working? No? Try something else.”

- If you notice you’re distracted, gently return to task. Don’t judge yourself—just return.

The micro-win practice:

Every 20-30 minutes, pause for literally 5 seconds and acknowledge what you’ve accomplished: “Got that section done. Good.” This builds intrinsic motivation (dimension 9) and keeps you engaged.

Step 6: Break and Reflect (10 minutes)

When the timer rings or you hit your goal:

- Stand up and move

- Get water

- Step outside if possible

Then briefly reflect:

- Did I hit flow today? If yes, what helped?

- If no, what was the obstacle? (Distractions? Wrong challenge level? Unclear goal?)

- What would make tomorrow’s session better?

This reflection loop is how you get better at engineering flow. You’re building meta-awareness of your own optimal conditions.

For more on building sustainable deep work practices, see The Complete Guide to Deep Work Cycles.

“My first attempt at this protocol: Phone buzzed 6 times (I forgot to move it), I remembered I needed to reply to an email (I didn’t), and I spent 10 minutes deciding what music to play (Spotify is a flow killer). Attempt two: Much better. Attempt twenty: Starting to feel like a functional human.”

What Kills Flow (And How to Protect Against It)

Let’s talk about flow’s natural predators.

1. Multitasking: The Flow Assassin

You cannot multitask into flow. Period. Every context switch costs you. Research shows it can take 23+ minutes to fully recover deep focus after an interruption.

The fix: One task. One window. One focus. Everything else waits.

2. Unclear Expectations

If you don’t know what “good” looks like, you can’t get feedback, and without feedback, you can’t maintain flow.

The fix: Before starting, define “done.” Get clear on standards. If you’re unclear, ask or decide for yourself.

3. Wrong Challenge Level

Boredom and anxiety are flow killers. Both signal a mismatch between challenge and skill.

The fix: Continuously calibrate. Make easy things harder, hard things smaller.

4. Social Interruptions

“Hey, quick question…” is the enemy of flow. Even well-meaning interruptions shatter concentration.

The fix: Set boundaries. Use Do Not Disturb. Schedule “office hours” for questions. Train your team/family that closed door = not available.

5. Lack of Autonomy

If you don’t have control over how or when you work, flow becomes nearly impossible.

The fix: Negotiate for focus blocks. Find the pockets where you do have control and protect them fiercely.

Flow Isn’t Just for “Creative” People

Here’s a myth worth busting: Flow isn’t just for artists, athletes, and musicians. Csíkszentmihályi found flow in assembly line workers, surgeons, administrative assistants, customer service reps—anywhere people could match skill to challenge and find meaning in the work.

I’ve experienced flow:

- Debugging code

- Writing email responses

- Organizing files

- Cooking dinner

- Having deep conversations

- Even washing dishes (I’m serious—the right music, the right mindset, and suddenly you’re in a Zen state with soap suds)

The activity matters less than the conditions. Any task that meets the nine dimensions can generate flow.

The Research That Backs This Up

Let’s ground this in science, because “trust me bro” only goes so far.

Csíkszentmihályi (1975, 1990) is the foundation. His original research involved thousands of interviews with people across cultures, ages, and professions. The nine dimensions of flow emerged from systematic analysis of these reports. This wasn’t armchair philosophy—it was rigorous qualitative research that later got quantitative validation.

Seligman (2011) integrated flow into his PERMA model of wellbeing:

- Positive emotion

- Engagement (flow lives here)

- Relationships

- Meaning

- Accomplishment

Seligman’s contribution was showing that flow isn’t just a pleasant experience—it’s a core component of psychological wellbeing. People who regularly experience flow report higher life satisfaction, lower depression, and greater resilience.

The neuroscience angle: More recent research using fMRI shows that during flow, the prefrontal cortex—the part of your brain responsible for self-criticism, time awareness, and conscious thought—actually quiets down. This is called “transient hypofrontality.” Your brain literally turns off the parts that would interfere with the task.

This explains dimensions 5 (merging action/awareness), 7 (loss of self-consciousness), and 8 (time distortion). Your brain is running lean, shutting down non-essential systems to maximize task focus.

For a deep dive into the neuroscience of flow and peak performance, check out Flow States and Your Brain: The Neuroscience of Optimal Performance.

Your Flow Practice Starts Now

Here’s your homework (except it’s not homework—it’s an invitation to feel better at work):

This week:

Choose three work sessions to experiment with flow:

- Pick a flow-worthy task

- Set up your environment (no phone, no distractions)

- Clarify your goal

- Set a 90-minute timer

- Stay with it

- Reflect afterward

Keep a flow journal:

After each session, note:

- Did I experience flow? (0-10 scale)

- What helped?

- What got in the way?

- One thing to improve next time

The pattern you’re looking for:

You probably won’t hit flow in your first session. That’s fine. You’re building the conditions. By session three or five, you’ll start noticing the feeling. By session ten, you’ll have figured out your personal formula.

The Deeper Truth About Flow

Flow isn’t just about productivity, though you’ll get more done. It’s not just about performance, though you’ll perform better.

Flow is about being fully alive in your work. It’s about finding the place where your skills meet the world’s challenges in a way that feels meaningful. It’s about remembering that work—even hard, demanding, frustrating work—can be a source of deep satisfaction.

Csíkszentmihályi spent his career studying happiness, and he concluded that flow experiences are among the most reliable paths to a life well-lived. Not pleasure. Not comfort. Not absence of challenge. But full engagement with meaningful challenges that stretch you without breaking you.

That’s what’s on the other side of understanding these nine dimensions. Not just better work sessions. A better relationship with work itself.

“Turns out, the thing I’ve been chasing—that feeling where work doesn’t feel like work—isn’t mystical or rare or reserved for geniuses. It’s just psychology. Very specific, very learnable psychology. And now that I know the recipe, I can actually cook it.”

Ready to Experience More Flow?

Start with your next work session. Pick one flow-worthy task. Eliminate distractions. Clarify your goal. Match challenge to skill. Set a timer. Stay focused.

See what happens.

And if you want to go deeper—if you want to build a sustainable practice of flow, focus, and mindful work—visit MindfulEngineer.ai for more resources, techniques, and a community of people learning to work with their minds instead of against them.

References:

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1975). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.