The same burnout every September. The same type of bad hire. The same argument with your partner. What if these aren’t isolated incidents—but features of a system you can finally see?

The symptoms kept recurring and now Marcus hit burnout for the fourth time.

Same symptoms: insomnia at 3 a.m., snapping at colleagues, that hollow feeling when opening his laptop. Same month too—late September, right when Q4 pressure ramped up. Same ending: two weeks off, promises to “do better,” then right back into the grind.

Sitting in his therapist’s office, she asked him a simple question: “What if this isn’t random? What if this is a pattern?”

Marcus laughed. “Of course it’s a pattern. I work too hard. Everyone knows that.”

“No,” she said. “I mean, what if there’s a structure to how you arrive here? A loop with identifiable stages that you could map?”

That question changed everything. Within a month, using a single-page exercise, Marcus identified not just that he burned out, but how the cycle worked: the trigger (new project), the behavior (overcommitment), the false reward (praise), and the crash (exhaustion). For the first time, he could see the whole loop. And seeing it meant he could finally interrupt it.

You probably have loops running in your life right now. Cycles you can’t quite name but definitely feel. The relationship pattern that keeps repeating. The financial spiral that happens every few months. The way certain situations always end the same way, and you’re left wondering: How did I end up here again?

These aren’t character flaws. They’re negative cycles—self-perpetuating behavioral loops that run on autopilot. And once you learn to see them, you can start to change them.

What Is a Negative Cycle? (And Why Your Brain Keeps Running It)

A negative cycle is a self-perpetuating loop where thoughts, emotions, and behaviors feed into each other, maintaining or worsening mental health issues and life patterns.

Here’s how it works:

The Thinking-Feeling-Behavior Loop:

Imagine you believe, deep down, that you’re not competent enough at your job. That’s the thought. This thought triggers anxiety—the feeling. To cope with the anxiety, you overwork and micromanage everything—the behavior. This behavior exhausts you, confirming your original thought: “See? I can’t handle this. I’m not good enough.” The loop closes. And repeats.

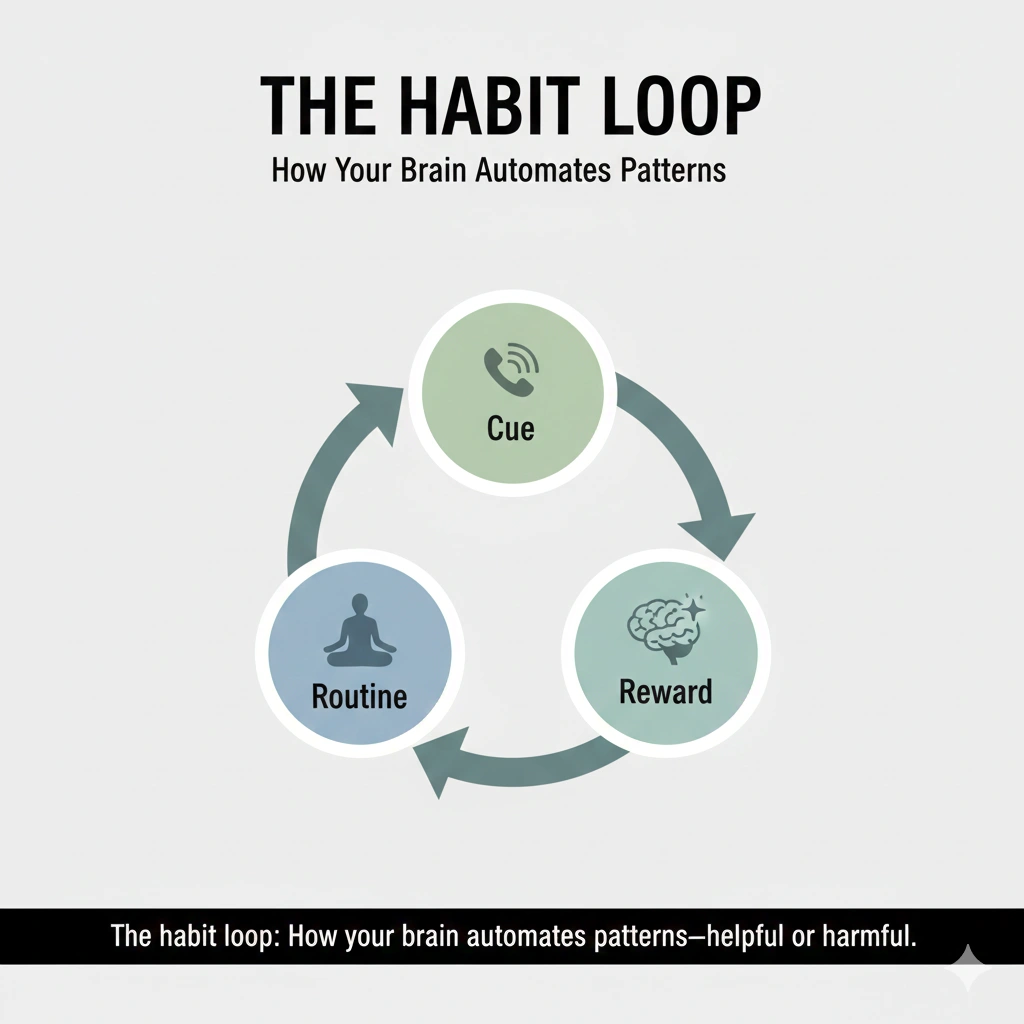

At the foundation of every habit is a neurological pattern called the habit loop, which consists of three key components: the cue, the routine, and the reward. The cue triggers the brain to initiate a behavior. The routine is the behavior itself. The reward provides satisfaction that reinforces the behavior. Over time, this loop becomes ingrained in neural pathways, creating patterns that occur almost subconsciously.

In Marcus’s case:

- Cue: New high-stakes project

- Routine: Say yes to everything, work 12-hour days, skip exercise

- Reward: Immediate praise, feeling indispensable

- Result: Burnout three months later

The insidious part? The reward is real. Habits are context dependent; they strengthen through repetition and associations with cues from the environment such that their expression becomes dependent on the relevant cues. The praise Marcus got felt good. The sense of being needed was addictive. His brain learned: Overwork = reward. The crash came later, but the neural pathway was already carved.

Neuroscientists have traced our habit-making behaviors to a part of the brain called the basal ganglia, which also plays a key role in the development of emotions, memories and pattern recognition. This is why negative cycles feel so automatic. Once formed, the decision-making prefrontal cortex essentially goes offline, and the basal ganglia runs the show.

Your brain isn’t trying to sabotage you. It’s trying to be efficient. The problem? It can’t distinguish between efficient and destructive. It just knows: This worked before (provided some reward), so let’s do it again.

The Long-Term Cost: When Loops Become Life Patterns

Negative cycles don’t just affect one area of life. They compound. They spread. They become your default operating system.

When several nodes keep reinforcing each other over time, vicious cycles can arise, from which it may be difficult to escape. These self-perpetuating patterns might explain the development and maintenance of mental disorders.

Consider the ripple effects:

The Burnout Loop: You overwork → You get rewarded → You neglect health → You lose energy → You compensate by working harder → Performance drops → You work even harder to compensate → Full burnout.

One study following a population through the pandemic found that a potential feedback loop involving sleep quality, fatigue and well-being was identified, where worrying caused poor sleep, which caused more fatigue, which diminished concentration, which reinforced worrying. The individuals stuck in this loop experienced significantly worse mental health outcomes two years later.

The Relationship Loop: You fear abandonment → You become clingy → Partner feels suffocated → They pull away → Your fear increases → You become more clingy → Relationship ends → Fear confirmed.

The Financial Loop: You feel stressed → You impulse-buy for relief → Credit card debt increases → Stress intensifies → You buy more to cope → Deeper debt → Shame and avoidance → Financial crisis.

Each cycle creates its own evidence. The pattern generates outcomes that seem to prove the pattern’s validity. You tell yourself: This is just who I am. But it’s not. It’s just a loop that’s been running long enough to feel like identity.

When a person who is in a depressed mood ruminates, they are more likely to remember more negative things that happened in the past, interpret situations in their current lives more negatively, and are more hopeless about the future. This can become a cycle where the more a person ruminates, the worse they feel, which then contributes to more rumination.

The psychological cost is profound. Research shows that these cycles contribute to:

- Chronic anxiety and depression

- Relationship dysfunction

- Career stagnation

- Physical health decline (chronic stress, poor sleep, weakened immune system)

- A pervasive sense of powerlessness

The physiological cost is real too. The persistent loop of negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors can entrench mental health problems if left unaddressed, influencing physical health and causing fatigue, sleep disturbances, and even physical ailments.

Here’s the hardest part: You can see the pattern in hindsight, but you can’t seem to catch it in real-time. It’s like watching a replay of a sports game where you know exactly what’s about to happen, but when you’re playing live, muscle memory takes over and you make the same mistakes.

Until you learn to map the pattern.

The Sneaky Nature of Destructive Loops: Why You Can’t See Them While They’re Running

Here’s why negative cycles are so difficult to escape:

1. They masquerade as solutions

The behavior in the loop often starts as a legitimate coping mechanism. Overworking does earn praise. Avoiding difficult conversations does provide short-term relief. Retail therapy does feel good in the moment. Reward-based learning has kept humans alive for thousands of years. The downside? Modern life is bombarded by artificial triggers designed to exploit your brain’s reward-based learning system.

Your brain registers the immediate reward and ignores the long-term cost. This is reward-based learning at its finest—and its most destructive.

2. They adapt to your awareness

You might notice you’re overworking and decide to “take it easy.” But the loop adapts. Instead of working late every night, you work late three nights a week and tell yourself you’ve improved. The cycle continues, just in a slightly different form.

Awareness provides the space to decide whether some habits and routines are beneficial or whether they are maladaptive, such as when habits can disrupt our aspirations and goals if they become too entrenched. But awareness alone isn’t enough if the underlying structure remains unchanged.

3. They feel like identity

When a pattern has run for years, it stops feeling like a behavior and starts feeling like you. “I’m just a perfectionist.” “I’m just bad with money.” “I’m just not good at relationships.” These statements aren’t descriptions of identity—they’re descriptions of unexamined loops.

4. They create cognitive blind spots

The seeming inability to escape can stem from deep-seated and perhaps subconscious insecurities, relying on old coping mechanisms that no longer serve us, being emotionally disconnected from our experiences, and seeking change without a concrete plan or direction.

You’re too close to see the pattern. It’s like trying to read a book with your nose pressed against the page. You see words, but not the sentence. You see events, but not the pattern.

5. They exist in your cognitive architecture

When we first learn something new, it requires active focus and attention from areas of the prefrontal cortex. But as we repeat the task, the basal ganglia takes over, allowing us to perform the action almost automatically. This shift from conscious effort to subconscious behavior makes habits powerful—and invisible.

Research from MIT shows that learning a habit is different from other kinds of learning: often we are not aware of developing a habit, and we develop it slowly over time. The process doesn’t seem to go in reverse, or else we don’t have access to the means to reverse it.

This is why willpower alone rarely works. You’re trying to consciously override an unconscious system. It’s exhausting. And ultimately, unsustainable.

The Life Heatmap: A Practical Exercise to Debug Your Loops

Enough theory. Let’s get practical.

The Life Heatmap is a single-page exercise that reveals your recurring patterns. It works for data nerds, visual thinkers, and anyone who’s tired of repeating the same mistakes.

Step 1: Pick Your Pattern

Choose one area where you suspect a negative loop is running:

- Career (burnout cycles, bad hires, project failures)

- Relationships (same arguments, same type of partner, same ending)

- Money (debt cycles, overspending, financial anxiety)

- Health (start-stop exercise routines, diet failures, stress-eating)

Don’t try to map everything at once. Pick the most pressing pattern—the one that’s costing you the most.

Step 2: Map the Last 5 Occurrences

On a single page, create five columns—one for each time this pattern played out. For each occurrence, document:

What was the trigger? (The cue that started the loop)

- New project assigned?

- Relationship milestone (moving in, engagement)?

- Financial stressor (unexpected expense)?

- Seasonal pattern (same month every year)?

What did you do? (The routine/behavior)

- Overcommitted to everything?

- Avoided difficult conversations?

- Made impulsive purchases?

- Pushed through exhaustion?

What was the reward? (The short-term payoff)

- Praise from boss/colleagues?

- Temporary relief from anxiety?

- Dopamine hit from shopping?

- Sense of control or accomplishment?

What was the crash? (The long-term cost)

- Burnout and medical leave?

- Relationship ended badly?

- Credit card debt?

- Injury or illness?

What did you tell yourself afterward? (The narrative)

- “I just need better boundaries”?

- “I chose the wrong person again”?

- “I’m bad with money”?

- “I’ll do better next time”?

Step 3: Look for the Common Thread

Once you’ve mapped five occurrences, step back and look at the whole page. What do you see?

- Same trigger appearing repeatedly? (Every time you get promoted, you burn out?)

- Same behavior in different contexts? (Avoiding conflict in work and relationships?)

- Same reward driving different behaviors? (Seeking validation through overwork and overspending?)

- Same crash point? (Always hitting bottom in September, or after six months?)

This is where patterns emerge. You’re looking for the structure, not just the symptoms.

Step 4: Name Your Loop

Give your pattern a name. Seriously. This matters.

“The Validation Treadmill” “The Avoidance Spiral”

“The September Burnout”

“The Six-Month Relationship Pattern”

Naming creates distance. It transforms “this is who I am” into “this is a system I’m running.” One feels like identity. The other feels like code you can debug.

Example: Marcus’s Life Heatmap

| Occurrence | Trigger | Behavior | Reward | Crash | Narrative |

| Burnout #1 (2019) | Promotion to lead | Worked 70hr weeks | Team hit deadline, got praised | Hospitalized, panic attacks | “I need to prove I deserve this” |

| Burnout #2 (2020) | New client project | Said yes to everything | Client loved me, renewed contract | Quit job abruptly | “I just took on too much” |

| Burnout #3 (2021) | Startup opportunity | Worked weekends, skipped vacation | Investors impressed | Relationship ended | “I chose the wrong partner” |

| Burnout #4 (2022) | Q4 product launch | Slept 4hrs/night for 3 months | Product shipped on time | Medical leave, depression | “I can’t keep doing this” |

| Burnout #5 (2023) | Started freelancing | Overbooked clients | Bank account grew | Chronic fatigue, burnout | “Maybe I’m not cut out for this” |

The common thread: Trigger = high-stakes opportunity. Behavior = overcommit and sacrifice health. Reward = external validation. Crash = total collapse.

Loop name: “The Validation Burnout Cycle”

Once Marcus saw this on paper, he couldn’t unsee it. The pattern was so clear. And for the first time, he realized: This wasn’t about finding better time management techniques. This was about a core belief driving a destructive loop: I’m only valuable when I’m overperforming.

How to Break the Cycle: Practical Intervention Strategies

Seeing the pattern is step one. Interrupting it is step two. Here’s how.

Strategy 1: Intercept at the Cue

What we know from lab studies is that it’s never too late to break a habit. Habits are malleable throughout your entire life. But the best way to change a habit is to understand its structure—once you tell people about the cue and the reward, it becomes much easier to change.

Once you know your trigger, you can catch the loop before it starts.

For Marcus: When a high-stakes opportunity appears (new project, new client), he now has a protocol:

- Pause for 24 hours before committing

- Ask: “What’s the minimum viable version of this?”

- Check: “Can I do this without sacrificing sleep/health/relationships?”

- If no, decline or renegotiate scope

The cue (opportunity) still appears. But he’s inserted a new routine (pause and evaluate) before the old routine (overcommit) can activate.

For relationship patterns: If your trigger is “three months in, when things get serious,” you can prepare. When that timeline approaches, instead of pulling away or picking fights, you could:

- Schedule a conversation about needs and expectations

- Journal about what you’re feeling

- Remind yourself: “This is the cue. The loop wants to run. I’m choosing something different.”

Strategy 2: Replace the Routine

The first step in breaking habits is identifying the cue that triggers the habit. Once the cue is identified, rather than simply trying to eliminate the behavior, the routine can be replaced with a healthier alternative.

You can’t eliminate the cue. You can’t remove the need for a reward. But you can change the behavior in between.

Old loop: Stress (cue) → Overspending (routine) → Temporary relief (reward)

New loop: Stress (cue) → 10-minute walk (routine) → Sense of calm (reward)

The new routine must provide some reward, even if it’s different from the original. Your brain needs something to latch onto. Over time, as the brain begins to associate the new routine with a rewarding feeling, the habit loop is gradually rewritten.

Strategy 3: Challenge the Reward

Research shows behavior change requires more than willpower, substitution strategies, and avoiding temptation. It’s more about hacking into your brain’s reward center to overcome cravings, stop destructive behaviors, and create a life you love.

Ask yourself: What reward am I actually getting from this behavior?

Sometimes the reward is obvious (dopamine from social media). Sometimes it’s hidden (avoiding vulnerability by staying busy). Once you identify the real reward, you can find healthier ways to get it.

Marcus’s real reward wasn’t praise. It was feeling worthy. He was outsourcing his sense of worth to external validation. The intervention wasn’t just “work less”—it was building internal validation through therapy, self-compassion practices, and redefining success on his own terms.

Strategy 4: Engineer Environmental Disruption

Interruptions to your routine—like a new work schedule, a different living situation, or even a vacation—can disrupt cues. When the signals that trigger your habits disappear, the habit loop breaks down.

Taking a vacation is so relaxing because it helps break certain habits. Changing a habit on a vacation is one of the proven most successful ways to do it because all your old cues and all your old rewards aren’t there anymore. So you have this ability to form a new pattern and hopefully carry it over into your life.

This is why New Year’s resolutions sometimes work. The calendar change creates a small environmental disruption—enough to interrupt old patterns and start new ones. You can create these disruptions intentionally:

- Rearrange your workspace

- Change your morning routine

- Take a different route to work

- Temporarily relocate (if possible)

The more you can change your environment, the easier it becomes to change your behavior.

Strategy 5: Build in Pattern Interrupts

Create deliberate checkpoints where you pause and ask: Is the loop running right now?

For Marcus, it’s a weekly review every Friday:

- Did I overcommit this week?

- Did I sacrifice health for work?

- Am I saying yes because it’s genuinely aligned, or because I’m seeking validation?

For relationship patterns, it might be monthly check-ins with a trusted friend:

- Am I pulling away again?

- Am I picking the same fight?

- Is this pattern showing up?

These interrupts don’t stop the loop entirely. But they create awareness in real-time, which is when you have the most power to change it.

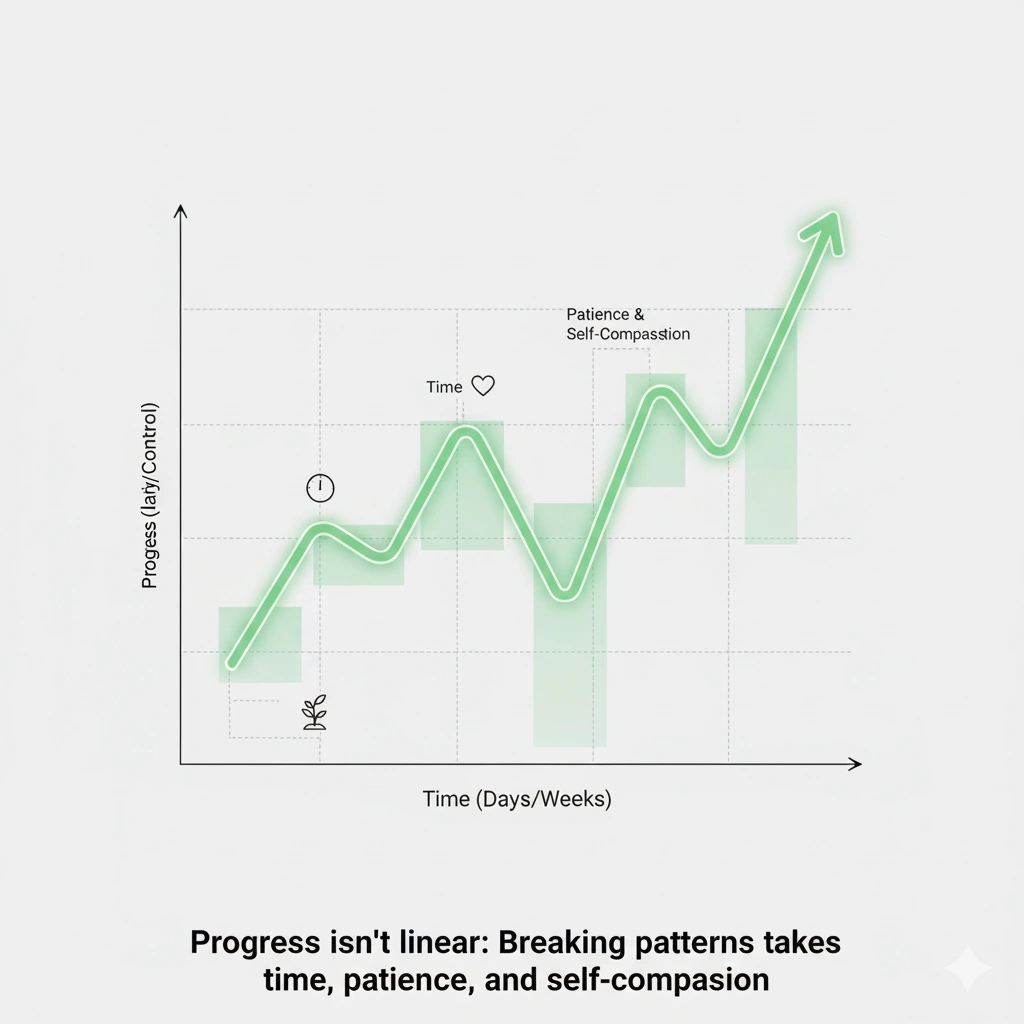

Consistency: Why Breaking Cycles Takes Time (And That’s Okay)

Here’s the truth nobody wants to hear: One realization won’t break the cycle.

Learning a habit is very slow. It takes many repetitions, often reinforced with positive feedback, before an action or series of actions become a habit. The same is true in reverse. Unlearning takes time.

Research on habit formation shows it can take 18 to 254 days to solidify a habit, with an average of 60-150 days. Breaking a habit follows similar timelines. You’re not flipping a switch. You’re carving new neural pathways.

What consistency looks like:

Weeks 1-2: You’ll catch the loop maybe once. Most of the time, you’ll realize you ran the full pattern only after the crash. That’s okay. Awareness is the first step.

Weeks 3-4: You’ll start catching it mid-loop. You’re already halfway through the behavior when you realize: Oh. I’m doing it again. You might not stop it, but you see it.

Weeks 5-8: You’ll catch it at the cue occasionally. The trigger appears, and you pause. Sometimes you’ll choose the new behavior. Sometimes the old loop still runs. Both are progress.

Weeks 9-12: The new pattern starts to feel more natural. You catch the cue more often. You replace the routine more consistently. The loop still tries to run, but you have more control over whether it does.

Months 3-6: The new behavior becomes more automatic. You’ve carved a new neural pathway. The old loop is still there—neural pathways don’t disappear—but the new one is stronger.

As learned behaviors become increasingly stereotyped and automatic, the sensorimotor loop takes a more active role in encoding the features of the behavior. This works in your favor when building new habits. The more you practice the new routine, the more automatic it becomes.

What helps maintain consistency:

- Track the pattern, not perfection: Don’t judge yourself for running the loop. Just document it. “The loop ran today. I caught it at [stage]. Next time I’ll try [intervention].”

- Celebrate micro-wins: You paused for five seconds before overcommitting? That’s huge. You noticed the trigger in real-time? That’s progress. You ran the loop but recovered faster? Win.

- Expect relapses: The loop will run again. Stress, exhaustion, major life changes—all of these can reactivate old patterns. This doesn’t mean you’ve failed. It means you’re human.

- Build support systems: Share your pattern with someone you trust. “I’m working on breaking [loop name]. If you notice me doing [behavior], can you point it out?” External accountability helps.

- Review quarterly: Every three months, revisit your Life Heatmap. Has the pattern changed? Are you catching it earlier? What’s working? What isn’t? Adjust your strategy accordingly.

Marcus still feels the pull of the Validation Burnout Cycle. The cue (big opportunity) still triggers the craving (prove your worth). But now he has a system. He recognizes the trigger, pauses, evaluates, and chooses consciously. Some months are better than others. But he hasn’t burned out in two years. That’s not perfection. That’s transformation.

Conclusion: From Loops to Liberation

You’ve been running patterns your whole life. Some serve you. Some sabotage you. Most run so quietly in the background that you don’t even know they’re there until they crash.

The Life Heatmap doesn’t solve the pattern. But it makes the invisible visible. And once you see the structure—the cue, the routine, the reward, the crash—you can start to change it.

Here’s what you now know:

Negative cycles are self-perpetuating loops where thoughts, emotions, and behaviors feed into each other, worsening patterns over time. They’re stored in your brain’s habit-making machinery, the basal ganglia, where they run on autopilot. They feel like identity, but they’re just code. And code can be debugged.

The intervention isn’t about willpower. It’s about awareness, structure, and repetition. Understanding and interrupting the habit loop—recognizing the cue and the reward—makes it much easier to change behaviors. You catch the cue, replace the routine, find new rewards, and practice until the new path becomes automatic.

It takes time. Research suggests 60-150 days to build new habits. It takes patience. You’ll relapse. The loop will run again. And that’s okay. What matters is that you see it faster, catch it earlier, and choose differently more often.

Three years ago, Marcus was on his fourth burnout and convinced he was broken. Today, he recognizes the Validation Burnout Cycle when it starts. He pauses at the trigger. He evaluates consciously. He chooses his commitments based on alignment, not approval.

He’s not perfect. The loop still tries to run. But he’s no longer trapped inside it.

You don’t have to be either.

Take out a single sheet of paper. Pick one pattern. Map five occurrences. Look for the thread. Name your loop. Then choose: the next time the cue appears, what will you do differently?

The pattern is already running. The question is: Will you keep running it unconsciously, or start debugging it intentionally?

The choice—and the clarity—is yours.

Research References:

- Rumination: A Cycle of Negative Thinking – American Psychiatric Association – Clinical overview of how negative thinking creates self-perpetuating cycles

- Identifying Cyclical Patterns of Behavior Using Data Analysis – PMC – Research on identifying cyclical patterns in destructive behavior

- Breaking the Cycle of Negative Behaviors Through Therapy – Grand Rising Behavioral Health – The thinking-feeling-behavior cycle in CBT

- The Psychology of Cycles – Psychology Today – Time-limited dynamic psychotherapy and cyclical maladaptive patterns

- Reframing Negative Thought Patterns – One Health Ohio – Rumination and its effects on mental and physical health

- New Perspectives on Repetitive Behaviour – PMC – Research on habits, routines, and maladaptive patterns

- A Vicious Cycle? Group-Level Analysis of Mental Health Variables – Cognitive Therapy and Research – Feedback loops in psychopathology and self-perpetuating patterns

- Breaking Free from Negative Cycles – Dr. Leslie Becker-Phelps – Why people repeat unhealthy patterns and how to break free

- How to Stop the Vicious Cycle – CBT and Dysfunctional Behaviour – Harley Therapy – Common maintaining processes in CBT

- Beck’s Cognitive Triad – ScienceDirect – Cognitive theories of depression and cyclical patterns

- Decoding the Habit Loop: The Neuroscience of Behavior Change – Integrative Psych – Neural mechanisms of habit formation

- The Science Behind Habits: How the Brain Forms and Breaks Them – Western University – The habit loop and basal ganglia function

- Break Habit Loops: How Curiosity Outperforms Willpower – Dr. Jan Anderson – Reward-based learning and habit hacking

- Habits: How They Form and How to Break Them – NPR – Interview with Charles Duhigg on the habit loop

- MIT Researcher Sheds Light on Why Habits Are Hard to Make and Break – MIT News – Neuroscience research on habit formation and the basal ganglia

- The Habit Loop: Breaking the Cycle of Triggers – Alignment With PrairieYana – Practical applications of understanding habit loops

- Interruptions in Habit Formation: Science Explained – Upskillist – How environmental changes disrupt habit loops

- Creatures of Habit: The Neuroscience of Habit and Purposeful Behavior – PMC – Corticostriatal circuits in habitual behavior

- The Habit Loop: How to Make & Break It – Reclaim – Practical guide to understanding and changing habit loops