Discover how what contemplatives have known for millennia is now verified by neuroscience—and why your brain’s transformation through daily practice might be the most important thing you learn this year.

Opening: The Unexpected Convergence

Imagine if something ancient—something practiced for thousands of years in temples and monasteries—turned out to be precisely what modern neuroscience says your brain needs to thrive. Imagine if practices developed without any scientific context ended up being optimized interventions for the exact neural problems modern life creates.

This is not imagination. This is what’s actually happening with mindfulness.

For 2,500 years, Buddhist contemplatives have sat quietly, training their minds through meditation. They developed sophisticated maps of consciousness. They documented the effects of practice. They refined techniques across centuries.

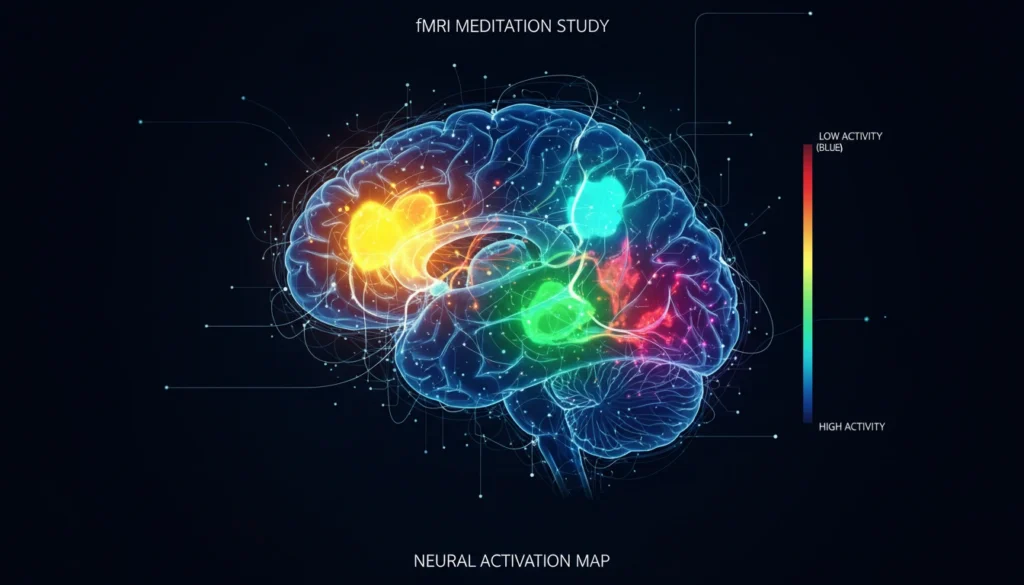

Then, beginning in the 1990s, neuroscientists started measuring what happens in the meditator’s brain using fMRI machines and EEG sensors. What they found was startling: the ancient practitioners weren’t just feeling better. Their brains were physically changing. Neural networks were reorganizing. Brain regions were growing. Gene expression was shifting.

The wisdom traditions were right. But not for the reasons they might have thought. They were right because meditation is a precise intervention for neural dysfunction. Because the human brain, shaped by millions of years of evolution for survival in dangerous environments, needs retraining for thriving in modern safety.

What’s remarkable is how perfectly mindfulness addresses nearly every neural problem modern life creates: stress, attention fragmentation, rumination, inflammation, accelerated aging, and disconnection from direct experience.

This convergence—ancient practice meeting modern science—suggests something profound: you possess a tool for transformation that’s been refined for millennia and now validated by the latest neuroscience.

Part 1: The Origins—Understanding Mindfulness’s 2,500-Year History

Mindfulness didn’t begin with modern science. It began in ancient India around the 5th century BCE with Siddhartha Gautama, who would become known as the Buddha.

The Buddha wasn’t claiming supernatural powers or divine revelation. He was doing something seemingly simple: he was sitting quietly and paying attention to his experience. He was noticing his thoughts. Observing his emotions. Feeling his bodily sensations. Without judgment. Without trying to change anything.

What he discovered was that this simple practice of paying attention had profound effects. It reduced suffering. It clarified the mind. It created peace.

He developed this into a systematic practice, which became the foundation of Buddhism. But crucially, he explicitly stated that people shouldn’t believe him just because he was Buddha. They should verify the practice through their own experience. “Come and see for yourself,” he taught.

This empirical approach—develop a practice, use it yourself, observe the results—is strikingly similar to the scientific method.

Over the following 2,500 years, Buddhist practitioners refined meditation techniques. They developed different styles for different temperaments and goals. They created detailed maps of consciousness—descriptions of different mental states that practitioners could access through practice.

The Tibetan Buddhist tradition developed detailed phenomenological accounts of meditation. The Thai tradition developed specific concentration practices. The Zen tradition developed rigorous training methods. Each tradition preserved thousands of years of accumulated knowledge about how the mind works and how to train it.

But this knowledge remained largely within contemplative communities. The Western world had little access to it.

The Modern Bridge: Bringing Ancient Practice into Scientific Context

In the 1960s and 1970s, a few Western scholars and scientists began encountering meditation traditions. Herbert Benson studied Transcendental Meditation practitioners and documented their physiological changes. Jon Kabat-Zinn brought Buddhist meditation into a hospital setting, stripped of religious language, and created what he called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

This was revolutionary. MBSR took a practice refined over 2,500 years and presented it in a format Western medicine could study. It was secular. It was measurable. It was applicable to health problems.

Simultaneously, neuroscience technology improved dramatically. fMRI machines could image the brain at high resolution. EEG systems could measure brain waves with precision. Genetic sequencing technology emerged. Researchers could finally measure what was actually happening inside meditators’ brains.

What followed was an explosion of research. Thousands of studies. Hundreds of replications. Consistent findings showing that meditation changes the brain in measurable, beneficial ways.

The wisdom traditions had been right. Not for mystical reasons, but for neuroscientific reasons. Meditation works because it retrains your brain for optimal functioning.

Part 2: The Modern Neuroscientific Understanding—What Happens in Your Brain During Mindfulness

Here’s what modern neuroscience has discovered about what mindfulness does to your brain:

The Default Mode Network Quiets

Remember the Default Mode Network—the brain system generating endless self-referential commentary? During mindfulness meditation, the DMN quiets significantly. The brain regions that normally busily narrate your life, ruminate about the past, and worry about the future become less active.

Simultaneously, the task-positive network (associated with focused attention) and the salience network (associated with present-moment awareness) activate more.

Your brain is literally shifting from internal narration to external presence.

The Prefrontal Cortex Strengthens

The prefrontal cortex—your brain’s executive center for decision-making, emotional regulation, and wisdom—becomes more active with meditation practice. More importantly, its connections to your amygdala (threat-detection center) strengthen.

This means your rational mind is gaining more control over your emotional reactivity. You’re not becoming emotionally numb. You’re becoming emotionally intelligent. You can feel emotions without being controlled by them.

The Amygdala Shrinks and Becomes Less Reactive

Your threat-detection center actually becomes physically smaller with sustained mindfulness practice. The amygdala’s reactivity to stressors decreases. Your nervous system becomes less prone to overreacting to perceived threats.

This is why meditators show less anxiety, less fear reactivity, more equanimity in the face of challenges.

Increased Gray Matter Density

In regions associated with learning, memory, emotional regulation, and perspective-taking, meditators show increased gray matter density. The brain is literally growing in regions that support wellbeing and wisdom.

Enhanced Neuroplasticity

Your brain becomes more capable of reorganizing itself. Neural pathways related to attention, compassion, and clarity strengthen. Pathways related to rumination and threat-reactivity weaken.

Your brain becomes more malleable, more able to change itself through practice.

Altered Brain Wave Patterns

As discussed in earlier articles, mindfulness increases alpha and theta waves (associated with relaxation and insight) and in advanced practitioners, increases gamma wave synchrony (associated with unified awareness and exceptional clarity).

These aren’t just electrical changes. They reflect fundamental shifts in how different brain regions are communicating and coordinating.

Vagal Tone Enhancement

The vagus nerve—the primary component of the parasympathetic nervous system—becomes more active and more capable of regulating your threat response. This has cascading effects throughout your body: lower inflammation, better immune function, improved digestion, better sleep.

What’s remarkable about all this is that these changes happen relatively quickly (within weeks) and can continue to deepen across years of practice.

Part 3: The Comprehensive Benefits—Why Mindfulness Is Effective for So Many Different Problems

Here’s something that might initially seem strange: mindfulness helps with stress, aging, focus, mood, immune function, pain, relationships, sleep, and cognitive function. How can one practice help with such different problems?

The answer is that all these problems share a common underlying issue: dysfunctional nervous system activation and suboptimal brain functioning. Mindfulness addresses the root, so it helps with the branches.

Stress Reduction

By activating the parasympathetic nervous system and reducing amygdala reactivity, mindfulness directly addresses the nervous system dysfunction driving chronic stress. Studies show 15–25% reductions in stress markers within weeks.

Aging Reversal

Through multiple mechanisms—telomere preservation, reduced inflammation, optimized gene expression, reduced oxidative stress—mindfulness literally slows cellular aging. People practicing mindfulness show biological ages 5–10 years younger than chronological age.

Enhanced Focus and Attention

By quieting the Default Mode Network and strengthening task-positive networks, mindfulness improves attention span, concentration, and cognitive clarity. Your ability to focus sustainably increases.

Improved Mood and Reduced Depression/Anxiety

Through amygdala reduction, prefrontal strengthening, and altered neurotransmitter regulation, mindfulness reduces depression and anxiety as effectively as some antidepressants. The effect is sustained, not just temporary.

Immune System Enhancement

Reduced stress hormones, increased anti-inflammatory gene expression, enhanced vagal tone—all contribute to immune system optimization. Vaccine responses improve by 50%. Infection susceptibility decreases.

Pain Management

By shifting pain processing away from sensory amplification regions toward regulatory regions, mindfulness reduces pain perception by 30–57%. This often outperforms pharmaceutical interventions.

Sleep Quality

Increased parasympathetic tone, reduced rumination, and normalized cortisol rhythm all improve sleep quality and duration. People practicing mindfulness sleep better within weeks.

Emotional Regulation

Stronger prefrontal-amygdala connections mean you can feel emotions fully while not being controlled by them. Your emotional intelligence increases.

Relationship Quality

Reduced reactivity, increased empathy (through mirror neuron activation in loving-kindness practices), and enhanced presence all improve relationship quality.

Cognitive Longevity

By reducing neuroinflammation, enhancing neuroplasticity, and preserving gray matter in aging-critical regions, mindfulness protects cognitive function as you age.

The beauty of this is that you’re not treating separate problems. You’re addressing a fundamental dysfunction in how your brain and nervous system are operating. By fixing that, you address multiple problems simultaneously.

This is why the Buddha taught that mindfulness helps with all suffering. Not through magical thinking, but through addressing the fundamental mechanism generating unnecessary suffering: an untrained nervous system.

Part 4: The Hidden Obstacles—Why Most People Struggle to Practice Consistently

The benefits are clear. The research is robust. And yet most people who try mindfulness don’t stick with it. Why?

The first challenge is expectation mismatch. You sit down to meditate expecting profound peace or dramatic insights. Instead, you’re bored. Your mind won’t stop jumping around. You feel restless. So you conclude it’s not working and quit.

The second challenge is the initial difficulty. Meditation is difficult. Your mind is used to constant stimulation. Sitting quietly feels unnatural. The first weeks are genuinely challenging as your brain adjusts.

The third challenge is the invisibility of benefits. You can’t feel your Default Mode Network quieting. You can’t sense your amygdala shrinking. You’re practicing on faith rather than tangible evidence.

The fourth challenge is the competing environment. Even as mindfulness trains your brain toward calm, if your life remains chaotic and stressful, your nervous system keeps getting reactivated. You need environmental support for practice to truly take root.

The fifth challenge is the long-term commitment required. The research shows consistent benefits require sustained practice. Many people expect that a few weeks of meditation will permanently solve their problems. When it doesn’t, they quit.

The sixth challenge is the lack of immediate feedback. With physical exercise, you can feel yourself getting stronger. With mindfulness, the changes are subtler and less immediately obvious.

The seventh challenge is the vulnerability meditation creates. As your mind quiets and your defenses relax, suppressed emotions and thoughts often emerge. This can be uncomfortable. Many people quit rather than process these surfacing emotions.

Part 5: The Simple Daily Practice—A 10-Minute Protocol You Can Start Today

Understanding the neuroscience of mindfulness is compelling. But what matters is practice. Here’s a simple, evidence-based 10-minute protocol that activates the specific neural changes discussed above.

Setup (1 minute)

Find a quiet space. Sit upright with feet flat or cross-legged on a cushion. Set a timer for 10 minutes. Close your eyes or maintain a soft downward gaze.

Part 1: Body Awareness Grounding (2 minutes)

Bring attention to your entire body. Feel where your body meets the seat. Feel your feet. Feel your hands. Notice the temperature of the air on your skin.

This grounds you in present-moment sensation and activates your salience network—your brain’s present-moment awareness system. Your Default Mode Network quiets because you’re directing attention to direct sensory experience rather than internal narration.

Part 2: Breath Awareness (4 minutes)

Shift attention to your natural breathing. Don’t try to change it. Just notice the sensations of breathing. The coolness of the inhale. The warmth of the exhale. The natural rhythm.

When your mind wanders—and it will—gently notice that it’s wandered and redirect attention back to the breath. This simple act of noticing mind-wandering and redirecting is the core practice. Every time you do it, you’re strengthening your prefrontal cortex and weakening Default Mode dominance.

This is where the neural change happens. Each redirection is a repetition training your attention networks to work better.

Part 3: Loving-Kindness (3 minutes)

In the final minutes, silently direct compassion toward yourself and others:

“May I be safe and healthy. May I be happy and at ease. May all beings be safe and healthy. May all beings be happy and at ease.”

This activates your prefrontal regions associated with empathy and social cognition. It further reduces amygdala reactivity. It enhances your parasympathetic nervous system.

Loving-kindness practice produces the most robust neural and physiological changes of any meditation style according to research.

The Key: Consistency Over Intensity

The research consistently shows that 10 minutes daily produces significant benefits. What matters is that you practice every day. Daily practice produces neuroplasticity changes. Sporadic practice produces minimal changes.

Set a specific time—right after waking, before bed, during lunch—and make it non-negotiable. Your brain learns through repeated signals: “Every day at this time, we practice mindfulness.”

Part 6: Where Ancient Wisdom and Modern Science Converge—Understanding the Profound Alignment

Here’s something remarkable worth sitting with: the descriptions ancient contemplatives provided of meditation experiences align almost perfectly with what modern neuroscience says is happening in the brain.

Ancient Buddhist texts describe meditation producing:

- Quieting of mental chatter: This describes Default Mode Network quieting

- Expanded awareness without self-reference: This describes reduced self-referential brain regions and increased salience network activation

- Emotional equanimity: This describes prefrontal strengthening and amygdala modulation

- Increased clarity and insight: This describes enhanced gamma wave synchrony and better inter-regional brain coordination

- Physical relaxation: This describes parasympathetic nervous system activation

- Reduced reactivity: This describes the therapeutic effect of reduced amygdala reactivity

The ancient meditators didn’t have fMRI machines. They didn’t have neurotransmitter measurements. But they had direct access to their own consciousness through introspective practice. They documented their experience.

And it turns out their descriptions were accurate descriptions of what neuroscience now measures.

This convergence suggests something profound: consciousness can be systematically studied through introspection. What contemplatives discovered through careful self-observation, neuroscience is now validating through objective measurement.

The practical implication is this: you don’t need to believe the neuroscience to benefit from practice. The contemplative traditions have 2,500 years of documented evidence that the practice works. The neuroscience simply explains the mechanism.

But knowing the mechanism can be motivating. When you understand that 10 minutes of meditation is literally changing your brain’s architecture, that it’s activating your healing genes, that it’s slowing your cellular aging—this knowledge can deepen your commitment.

Part 7: Conclusion and the Way Ahead—Your Personal Neuroscience Practice

We began this article with a remarkable observation: something ancient turned out to be precisely what modern neuroscience says your brain needs.

That observation deserves to be deepened into a commitment.

You now understand something that most people never learn: that your brain is not fixed. That it responds to practice. That through daily mindfulness, you can reshape your neural architecture. You can quiet your threat-detection system. You can strengthen your emotional regulation. You can slow your aging. You can change your genetic expression. You can literally transform your consciousness.

This isn’t mystical. It’s neuroscience. It’s been verified across thousands of studies. It’s waiting for you.

The way ahead is simple:

Begin with 10 minutes daily. Choose a specific time and make it non-negotiable. Practice the protocol described above. Expect your mind to wander. When it does, gently redirect it. Don’t judge yourself. Don’t expect profound experiences. Just practice consistently.

After 4 weeks, you’ll likely notice subtle shifts. You’ll be slightly less reactive. Slightly more present. Sleep might improve. Mood might lift.

After 8 weeks, the changes become more noticeable. You’ll realize your mind doesn’t wander as much in daily life. Situations that would have triggered anxiety now feel more manageable. You have more energy.

After 3 months and beyond, significant changes accumulate. Your baseline consciousness shifts. You’re fundamentally different. Your brain has been rewired.

This isn’t a metaphor. This is what neuroscience shows happens.

And here’s the beautiful part: what the contemplatives discovered 2,500 years ago is now accessible to you. Not as religious doctrine or mystical teaching, but as a scientifically validated practice for optimizing your brain and transforming your life.

The wisdom is ancient. The science is modern. The opportunity is now.

The Invitation

You’re living in a remarkable moment in human history. For the first time, ancient contemplative practices and modern neuroscience have fully converged. We understand both why meditation works and how it works.

You possess a tool refined over 2,500 years and validated by contemporary science. A tool that can reduce your stress, slow your aging, enhance your focus, improve your mood, optimize your immune function, and quite literally rewire your brain for greater peace and clarity.

The question is: are you willing to commit to 10 minutes daily to access the transformation this practice makes possible?

References & Further Reading

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life. Hyperion.

- Davidson, R. J., & Begley, S. (2012). The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live—and How You Can Change Them. Hudson Street Press.

- Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163-169.

- Hölzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Gard, T., & Lazar, S. W. (2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Research, 191(1), 36-43.

- Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y. Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20254-20259.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213-225.

- Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind and Body. Bantam.

- Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433-447.

- Black, D. S., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness and the inflammatory response. Health Psychology Review, 10(2), 144-159.

- Zeidan, F., Martucci, K. T., Kraft, R. A., Gordon, N. S., McHaffie, J. G., & Coghill, R. C. (2011). Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(14), 5540-5548.

- Kaliman, P., Álvarez-López, M. J., Cosín-Tomás, M., Rosenkranz, M. A., Lutz, A., & Davidson, R. J. (2014). Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 40, 96-107.

- Epel, E. S., & Prather, A. A. (2018). Stress, telomeres, and psychoneuroimmunology: Exploring the connectedness. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 74, 1-8.

Bhikkhu Bodhi (1995). The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya. Wisdom Publications.