Discover the hidden neuroscience of pain perception—and how meditation can reduce your suffering by 30–57% by literally rewiring which brain regions process your pain.

Opening: The Sensation That Isn’t What You Think It Is

Right now, if you have chronic pain somewhere in your body—a bad knee, lower back tension, migraines, fibromyalgia—you probably think that pain is coming from that location. You think your knee is sending a pain signal to your brain, and your brain is faithfully reporting what it feels.

This assumption is deeply wrong.

Pain isn’t a direct signal from your tissue to your brain. Pain is a construction. Your brain is actively creating it.

This isn’t to say your pain isn’t real. It’s absolutely real. You feel it. It affects your life. It limits your activities. It steals your peace. But the pain you feel is not simply a passive reporting of what’s happening in your tissue. It’s an interpretation. A prediction. A story your brain is telling based on multiple sources of information—tissue damage (maybe), threat perception, emotional state, attention focus, past experiences, and beliefs about what the pain means.

And here’s what changes everything: if pain is something your brain constructs, then your brain can reconstruct it.

Through mindfulness practice, you can literally change how your brain processes pain signals. You can shift activity away from the brain regions that amplify suffering and toward the regions that regulate it. You can reduce your perceived pain by 30–57%—often outperforming pharmaceutical interventions.

This isn’t pain tolerance. This isn’t “sucking it up” or ignoring suffering through willpower. This is actual neurological change. Your brain processing the same stimulus differently.

The research is decisive. The mechanism is understood. And it’s available to you.

Part 1: What Is Pain Perception? Understanding the Brain’s Construction

Before you can change pain perception, you need to understand what it actually is—and this requires understanding that your brain isn’t passively receiving pain signals. It’s actively generating your experience of pain.

For most of the 20th century, neuroscience operated under what was called the “gate control theory” of pain. According to this model, pain was like a message traveling up a specific pathway from your tissue to your brain. If the gate was open, the message got through and you felt pain. If the gate was closed, the message didn’t reach your brain and you felt nothing.

This model was helpful, but incomplete. It suggested that pain perception was relatively straightforward—tissue damage → pain signal → suffering.

But neuroscience has learned something more sophisticated: pain is a multidimensional experience generated by your brain using information from multiple sources.

When you have a physical injury—say, you cut your finger—yes, nociceptors (specialized pain-sensing nerve endings) fire. This information travels up your spinal cord to your brain. But here’s where it gets interesting: your brain doesn’t simply record this signal. It integrates it with dozens of other sources of information.

It asks: What attention am I paying to this signal? What emotions am I feeling? What does this signal mean? Am I in danger? What’s my historical experience with similar signals? What have I been told about what this means? What’s my current stress level? My emotional state? My beliefs?

Based on all this information, your brain generates a unified experience: pain.

This process happens largely outside your conscious awareness, but it’s real and it’s measurable.

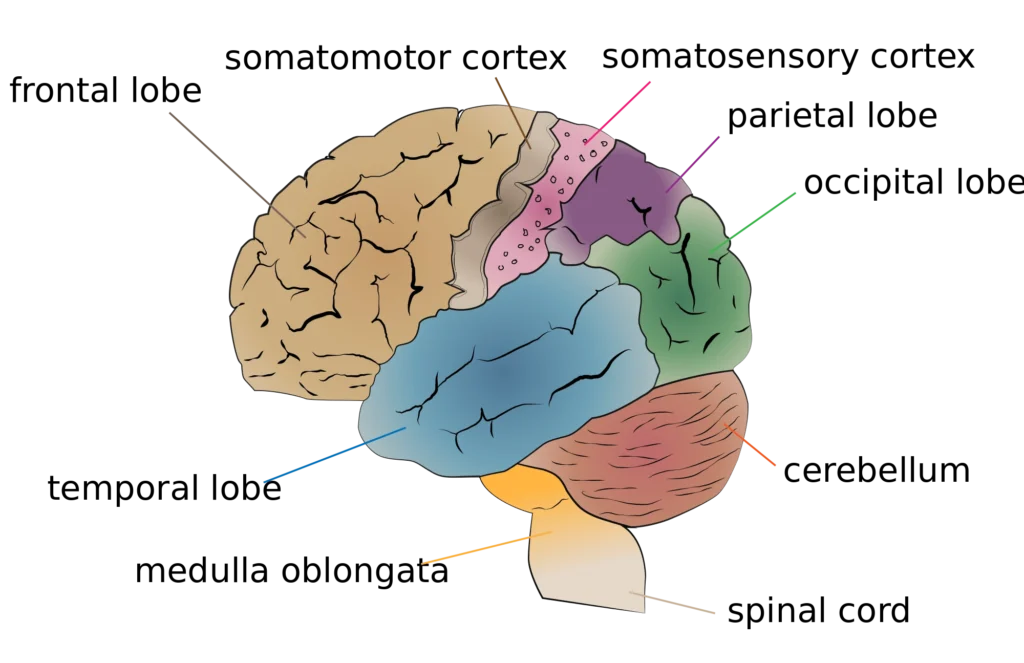

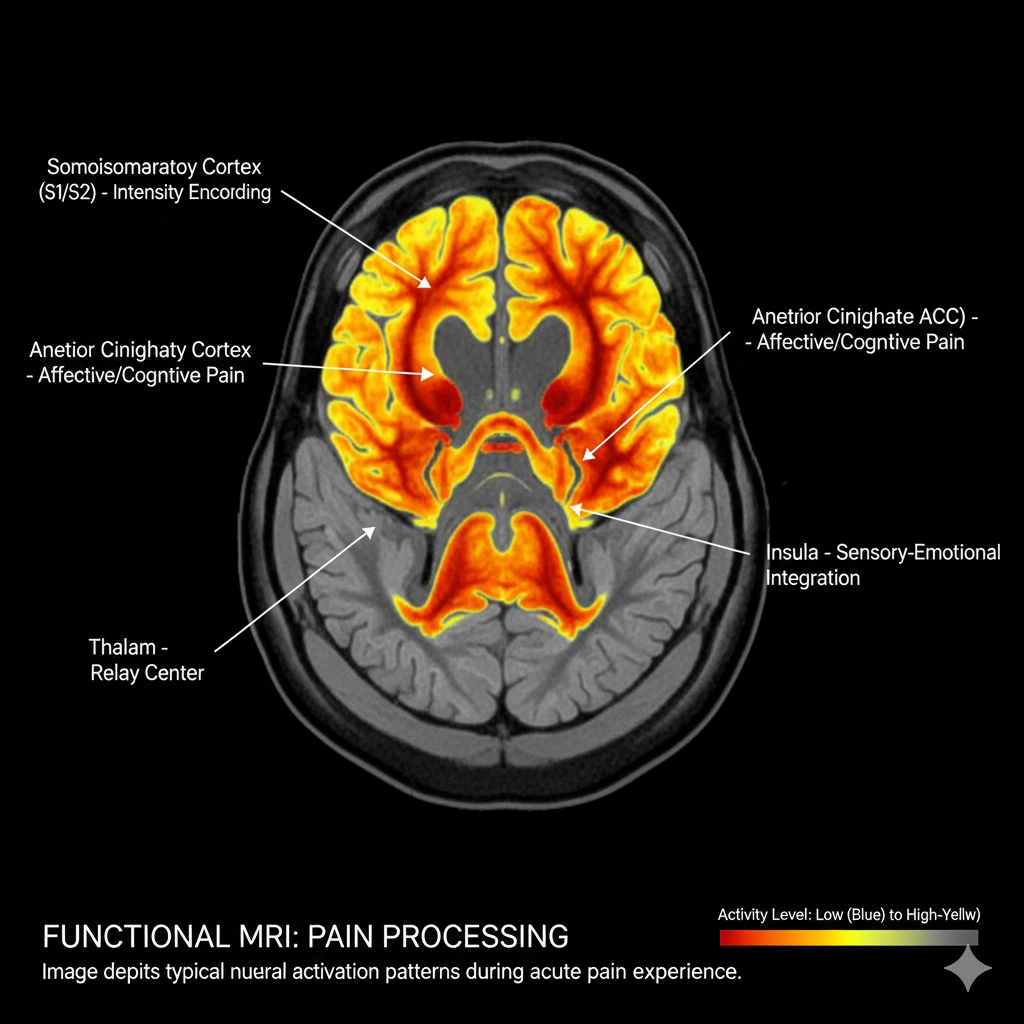

The primary region processing the sensory dimension of pain is your somatosensory cortex—the area that registers where the pain is and what it feels like physically. But pain isn’t just the somatosensory experience. It also involves your anterior cingulate cortex (which processes the emotional dimension of pain—how much it bothers you), your insular cortex (which generates body awareness), and your prefrontal cortex (which can regulate and recontextualize pain).

The key insight is this: the intensity of pain you experience depends partly on what’s happening in your somatosensory cortex (the sensory processing), but it depends even more on what’s happening in the emotional and regulatory regions.

When your anterior cingulate cortex is highly activated (indicating emotional distress about the pain), you experience more suffering. When your prefrontal cortex is active (indicating cognitive control and recontextualization), you experience less suffering—even though the sensory signal might be identical.

This is why the same physical stimulus can feel like barely noticeable discomfort one day and unbearable pain another day. It depends on your mental state, your attention, and your interpretation.

And this is the doorway through which mindfulness enters.

Part 2: The Suffering Multiplier—How Pain Perception Constrains Your World

Chronic pain isn’t just physical discomfort. It’s existential. It constrains how you move through the world. It shapes what you’re willing to attempt. It colors your emotional landscape.

When you’re in chronic pain, your brain treats the pain signal as high-priority information. Your attention naturally gravitates toward it. Every movement you make is filtered through “Will this hurt?” Your nervous system becomes hypervigilant to pain signals.

This creates a vicious cycle. Pain commands your attention. Attention to pain amplifies your perception of pain. The amplified perception triggers emotional distress. Emotional distress further sensitizes your nervous system to pain signals. The cycle deepens.

Over time, chronic pain reshapes your life. The activities you love become inaccessible. Your social participation decreases. Your mood becomes depression-tinged. You begin to identify with the pain. “I’m someone with chronic pain” becomes your identity rather than “I’m someone experiencing pain.”

This is why chronic pain is so devastating psychologically, not just physically. It’s not just the sensation. It’s the way pain constrains possibility. The way it narrows your world to the size of your suffering.

And here’s what’s crucial: this psychological component is where mindfulness intervenes most powerfully.

When you’re trapped in the pain-attention-amplification cycle, your brain is operating in a particular mode. It’s contracted. It’s focused narrowly on threat (the pain). Your prefrontal cortex—the region capable of stepping back and seeing the larger context—is relatively quiet.

Mindfulness practice interrupts this cycle at a fundamental level. It trains your brain to relate to pain differently—not by denying it or suppressing it, but by changing how your brain processes it.

Part 3: The Mindfulness Intervention—How Meditation Rewires Pain Processing

Here’s what happens in your brain when you practice mindfulness in the presence of pain.

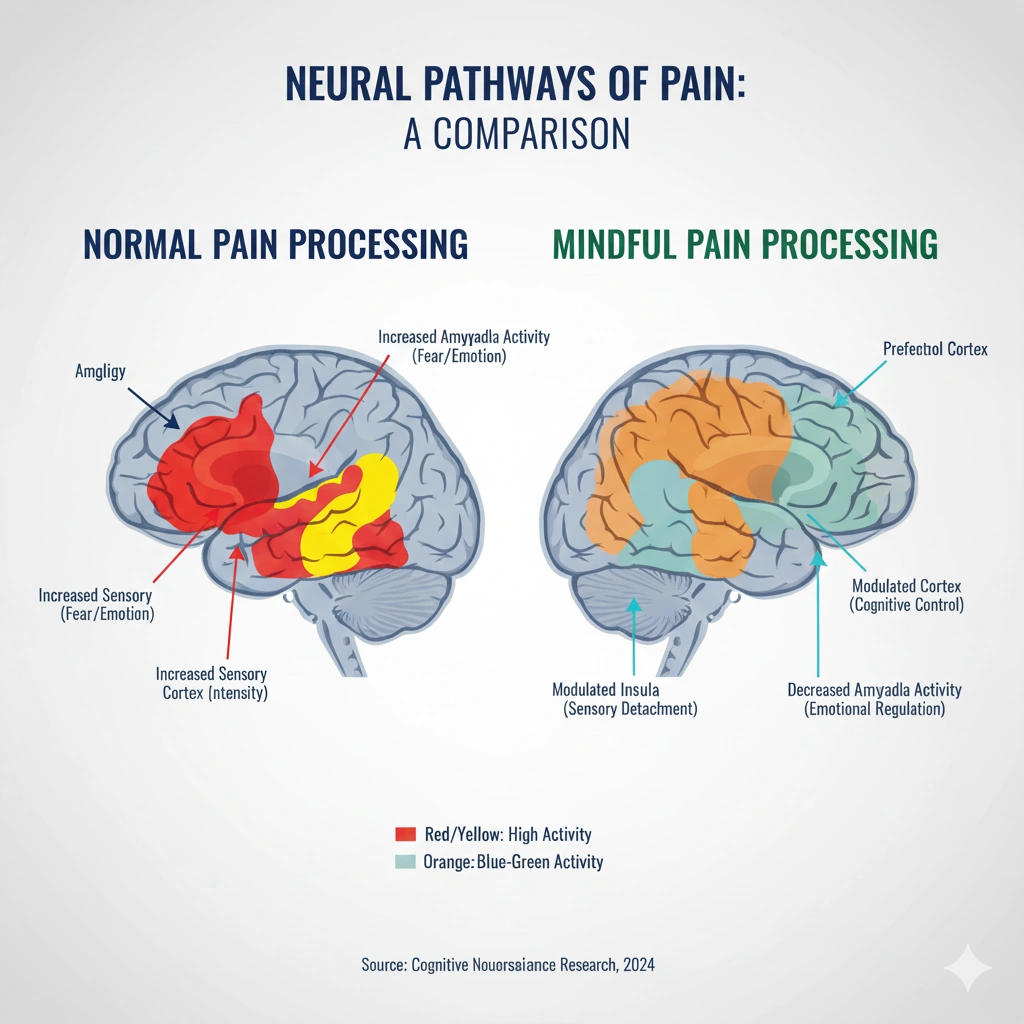

Normally, when you experience pain, your attention automatically orients toward it. Your brain treats it as high-priority information demanding your focus. The somatosensory cortex is highly activated (registering the sensation), and your anterior cingulate cortex is highly activated (generating emotional distress about the sensation).

Now introduce mindfulness. You sit with the pain. You bring gentle awareness to it. You notice it without judgment. You don’t try to make it go away. You don’t resist it. You don’t create a story about what it means.

Something shifts. Your somatosensory cortex—the area processing the raw sensation—actually becomes less active. The intensity of sensory processing decreases.

Simultaneously, your prefrontal cortex becomes more active. This is the region responsible for cognitive control, perspective-taking, and recontextualization. You’re accessing the part of your brain that can step back and relate to the pain differently.

The result: the same pain signal is being processed by different brain regions. Less activity in the sensory amplification areas. More activity in the regulatory areas.

And here’s the crucial part: this shift in brain processing translates directly to reduced perceived pain. You’re not denying the pain. You’re not suppressing it. You’re literally processing it through different neural pathways that generate less suffering.

The mechanism is fascinating because it reveals something profound about the nature of pain: pain isn’t monolithic. It’s not one thing. It’s made up of a sensory component (what the pain feels like) and an affective/emotional component (how much you suffer about the pain).

You can significantly reduce the affective component—the suffering—without changing the sensory component. And when you reduce the suffering dimension, the overall pain experience becomes much more tolerable.

This is what mindfulness does. It doesn’t make pain disappear. It changes your brain’s relationship to pain so that suffering decreases even when sensation persists.

Part 4: The Evidence—What Research Shows About Mindfulness and Pain Reduction

For decades, pain management relied primarily on pharmaceutical interventions or invasive procedures. But over the past 15 years, a body of research has emerged showing that mindfulness-based interventions produce some of the most significant pain reductions ever documented—often rivaling or exceeding medication.

The Landmark Zeidan Studies: Direct Brain Imaging Evidence

In 2011, Fadel Zeidan at Wake Forest University conducted a study that would become foundational for understanding how mindfulness reduces pain. He brought people into a brain imaging lab and exposed them to painful heat stimuli while scanning their brains.

First, he established their baseline pain response. Then he gave them brief mindfulness training—just 4 days of 20-minute sessions. Then he scanned them again while applying the same painful stimuli.

The results were striking. With just four days of mindfulness training, participants showed:

- Decreased activity in the somatosensory cortex (the region processing pain sensation)

- Increased activity in the prefrontal cortex (the region that regulates pain perception)

- Reported pain reduction of 40% compared to baseline

This wasn’t placebo. It was measurable brain change producing measurable pain reduction.

But Zeidan didn’t stop there. He replicated and expanded this research in subsequent studies.

In 2015, he published a follow-up study examining pain reduction in experienced meditators. The results were even more dramatic. Long-term practitioners showed:

- 50% greater pain reduction compared to control groups

- Significantly less activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (the emotional/suffering dimension of pain)

- Brain activity patterns suggesting they were literally “deactivating” their pain response

In 2022, Zeidan published a comprehensive review of his research spanning multiple studies. The findings were consistent: mindfulness-based interventions produced pain reduction ranging from 30–57%, with most studies showing reductions in the 40–50% range.

What made these findings even more significant was how they compared to other interventions. Zeidan’s research directly compared mindfulness to:

- Placebo analgesia (the pain relief you get from believing a treatment will help): Mindfulness outperformed placebo. Participants receiving mindfulness training showed greater pain reduction than those receiving placebo treatment.

- Morphine-level opioid analgesia: The pain reduction from mindfulness was comparable to the pain reduction from opioid medications—without the side effects or addiction risk.

This is remarkable. A simple mental practice—mindfulness—produced pain reduction equivalent to powerful drugs, but through a completely different mechanism.

Additional Landmark Studies: Chronic Pain Conditions

Beyond Zeidan’s work, other researchers examined mindfulness effects on specific chronic pain conditions:

- A 2016 study in Pain Medicine found that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) reduced fibromyalgia pain by 47% on average, with effects sustained at 6-month follow-up.

- A 2014 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine examined mindfulness for chronic low back pain. It found that mindfulness was more effective than standard medical care at reducing pain and improving function.

- A 2013 meta-analysis examining 22 studies on mindfulness and chronic pain found consistent evidence for 30% average pain reduction across diverse pain conditions.

The Mechanism Studies: Understanding Why Mindfulness Works

Researchers have gone deeper, examining the specific mechanisms by which mindfulness reduces pain. Multiple studies have shown:

- Attention decoupling: Mindfulness training teaches your brain to decouple attention from pain. You become less likely to automatically orient toward pain signals.

- Reappraisal capacity: Your prefrontal cortex becomes better at recontextualizing pain—seeing it as a sensation rather than a threat.

- Reduced catastrophizing: Mindfulness reduces the tendency to catastrophize about pain (creating worst-case narratives). This catastrophizing is a major driver of pain perception amplification.

- Increased acceptance: Rather than fighting pain, mindfulness practitioners develop what’s called “pain acceptance”—relating to pain without resistance. Paradoxically, this acceptance produces greater pain reduction than effortful attempts to suppress or escape the pain.

A particularly elegant 2018 study published in Neuroscience of Consciousness directly measured how mindfulness changes pain processing. Researchers found that with mindfulness training, participants’ brains showed:

- Reduced connectivity between the default mode network (the areas activated during mind-wandering and self-referential thinking) and the pain-processing regions

- Increased connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and pain-processing regions

- In essence: the part of your brain that creates suffering narratives was becoming less connected to pain signals, while the part that regulates and recontextualizes was becoming more connected

Timeline: How Quickly Does Pain Reduction Happen?

One of the most encouraging findings: pain reduction happens relatively quickly. Zeidan’s research showed measurable effects after just 4 days of 20-minute mindfulness sessions. Significant effects typically appear within 4–8 weeks of consistent practice.

This is different from some other benefits of mindfulness (like neuroplasticity changes), which take longer. For pain specifically, the brain seems to respond quite rapidly to training in a different way of processing pain signals.

Part 5: The Hidden Obstacles—Why Most People Don’t Experience These Pain Reductions

The research is compelling. You might read that mindfulness can reduce pain by 30–57% and think, “This is exactly what I need. I’m going to start meditating tomorrow.”

But between the research and the results lies a gap that most people don’t anticipate.

The first challenge is the counterintuitive nature of the practice. The research shows that resistance and avoidance amplify pain, while acceptance reduces it. But when you’re in pain, your natural instinct is resistance. “Make it go away. Fix this. Do something.” Mindfulness asks you to do the opposite: to turn toward the pain with gentle curiosity. This goes against every instinct your nervous system has developed.

The second challenge is the initial pain amplification. When you first bring mindful attention to pain—really noticing it rather than avoiding it—the pain often feels more intense initially. Your awareness is now more focused on the sensation. This can feel like mindfulness is making things worse, so you quit just as the practice is beginning to work.

The third challenge is the timing of practice. The research showing 30–57% pain reduction involves consistent daily practice. Most people try occasional meditation and expect similar results. When the results don’t materialize, they assume mindfulness isn’t working for them.

The fourth challenge is the misconception about what mindfulness does. Many people think mindfulness will make pain disappear. When the pain is still there (but perhaps less emotionally charged), they feel like the practice failed. They didn’t understand that mindfulness doesn’t eliminate pain sensation; it reduces suffering about pain.

The fifth challenge is underlying trauma or sensitization. In cases of severe chronic pain, PTSD, or complex trauma, the nervous system might be so sensitized that it’s resistant to the “safety signals” that mindfulness is trying to send. The practice can help, but it might require professional guidance or additional therapeutic support.

The sixth challenge is integration with daily life. You might practice mindfulness meditation daily and experience pain reduction during the meditation. But if you return to your daily life unchanged—same activities, same ergonomics, same stress—the pain often returns. The mindfulness helps, but it’s not a substitute for addressing the conditions generating the pain.

The seventh challenge is medication interactions. If you’re taking strong pain medications, your perception of pain is already chemically altered. Mindfulness can still help, but the effects might be smaller and the practice might require adaptation.

Part 6: The Pathway to Pain Transformation—Practical Solutions

Understanding how mindfulness rewires pain processing is intellectually interesting. Actually reducing your pain requires a practical approach grounded in how your nervous system actually learns.

Foundation: 20 Minutes Daily for 8 Weeks

The research showing 30–57% pain reduction involves consistent daily practice. Zeidan’s research showed effects after just 4 days, but sustained significant reduction requires ongoing practice. Aim for 20–30 minutes daily for at least 8 weeks.

This isn’t arbitrary. Your nervous system needs time to genuinely learn a new way of processing pain signals. Sporadic practice helps, but consistent daily practice produces the most dramatic effects.

Start With Guided Pain-Specific Practices

Generic meditation is helpful, but mindfulness practices specifically designed for pain are more effective. Mindfulness-Based Pain Management (MBPM) programs are structured specifically for pain reduction. These programs often include:

- Body scan meditations (noticing sensations throughout your body without judgment)

- Breathing practices that anchor attention

- Loving-kindness meditation (generating compassion for yourself, which reduces pain-related suffering)

- Walking meditation for moving through pain without fighting it

These approaches are more effective than generic mindfulness because they specifically train your brain in the particular attention-shifting necessary for pain processing changes.

The Key Shift: From Fighting to Observing

The most crucial mindset shift for pain reduction is moving from “I need to make this pain go away” to “I’m going to observe this pain with curiosity.” This isn’t acceptance in a passive sense. It’s active, engaged observation.

When you observe pain with curiosity rather than resistance, something neurological happens. Your threat-detection system quiets. Your prefrontal cortex becomes more active. Your somatosensory cortex activity decreases. You’re literally shifting the brain regions processing the signal.

Practically, this means when pain arises:

- Notice where it is in your body

- Observe its qualities: Is it sharp or dull? Hot or cold? Pulsing or constant?

- Notice how it changes moment to moment

- Breathe with it rather than against it

- Approach it with gentle curiosity: “What is this sensation actually like when I stop fighting it?”

This is the core of pain-specific mindfulness practice.

Measurement: Track Your Pain Ratings

You can’t directly measure brain activity changes without fMRI. But you can measure your pain perception. Use a simple 0–10 pain scale:

- Rate your pain each morning before practice

- Rate it immediately after practice

- Rate your average pain levels throughout the day

After 4 weeks of consistent practice, you should see measurable reductions in these ratings. After 8 weeks, significant reductions (often 20–40%) are common.

Seeing this objective data is profoundly motivating. It provides concrete evidence that your practice is working—that your brain is actually rewiring.

Integration: Address the Physical Conditions

Mindfulness is powerful for pain perception, but it’s not a substitute for addressing physical factors generating pain. While practicing:

- Work with physical therapy or appropriate movement specialists

- Improve ergonomics at work and home

- Address inflammation through diet and exercise

- Ensure adequate sleep

- Manage stress through lifestyle changes

Mindfulness handles the perception and suffering dimensions. These other interventions address the tissue-level factors. Together, they create comprehensive pain management.

Advanced: Professional Guidance

For severe chronic pain, working with a pain psychologist or mindfulness teacher trained specifically in pain management can accelerate progress. These professionals understand the specific challenges of pain-based practice and can guide you past obstacles that might otherwise derail your practice.

Part 7: The Liberation—What Pain Reduction Actually Restores

When your brain begins processing pain differently—when somatosensory activity decreases and prefrontal regulation increases—something shifts that goes beyond just “feeling better.”

Your world expands. Activities that became inaccessible because of pain fear become possible again. You can walk further. Sit longer. Engage in movement without constant threat assessment.

Your attention becomes available for life. Instead of constant monitoring for pain signals, your awareness can expand to include the people around you, the beauty of your environment, the work you’re doing. You’re no longer imprisoned by internal threat-detection.

Your emotional landscape transforms. When pain stops driving constant suffering narratives, depression lifts. Anxiety quiets. You gain access to joy and peace that were unavailable when pain was dominating your consciousness.

Your sense of agency returns. You’re no longer a victim of your condition. You’ve learned that your brain can change how it processes pain. You have tools. You have power. You can influence your own experience.

And perhaps most importantly: your relationship to suffering transforms. You learn viscerally that suffering isn’t fixed. That pain and suffering aren’t the same thing. That your brain can relate to sensation in ways that reduce anguish.

This understanding—that your brain is plastic, that you’re not trapped in pain, that different processing is possible—often becomes more valuable than the pain reduction itself.

That’s what happens when you rewire your pain processing through mindfulness.

The Invitation

You’re probably in pain right now. Or you know chronic pain intimately. And you’ve probably tried many things—medications, physical therapy, alternative treatments. Some helped. Some didn’t.

The research is clear: your brain is actively generating your pain experience. And your brain can learn to generate that experience differently. Through mindfulness practice, you can shift which brain regions process your pain. You can reduce suffering by 30–57%.

This isn’t mystical. This isn’t optimistic thinking. It’s measurable neuroscience backed by fMRI imaging, clinical trials, and hundreds of replicated studies.

The question is: are you willing to give yourself 20 minutes daily for 8 weeks to train your brain in a new way of processing pain?

References & Further Reading

- Zeidan, F., Martucci, K. T., Kraft, R. A., Gordon, N. S., McHaffie, J. G., & Coghill, R. C. (2011). Brain mechanisms supporting the modulation of pain by mindfulness meditation. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(14), 5540-5548.

- Zeidan, F., Grant, J. A., Brown, C. A., McHaffie, J. G., & Coghill, R. C. (2012). Mindfulness-related changes in brain activity during an acute pain experience. Journal of Pain, 13(12), 1219-1229.

- Zeidan, F., Vago, D. R., & Coghill, R. C. (2022). Mindfulness and pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(5), 377-390.

- Garland, E. L., Gaylord, S. A., & Park, J. (2009). The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 5(1), 37-41.

- Veehof, M. M., Oskam, M. J., Schreurs, K. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2011). Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 152(4), 730-741.

- Hilton, L., Hempel, S., Ewing, B. A., Apaydin, E., Xenakis, L., Newberry, S., … & Shekelle, P. G. (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199-213.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213-225.

- Gazzaley, A., & Rosen, L. D. (2016). The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World. MIT Press.

- Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., … & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16(17), 1893-1897.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822-848.

Eccleston, C., & Crombez, G. (1999). Pain demands attention: A cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 356-366.