Discover how quieting your Default Mode Network can free you from obsessive thinking, restore presence, and unlock the peace that exists beneath constant mental noise.

Opening: The Voice That Never Stops

Right now, there’s a narrator running in your head. It might be commenting on what you’re reading. It might be replaying a conversation from this morning. It might be planning tomorrow. Worrying about the future. Rehashing the past.

This narrator is so constant, so woven into the texture of your consciousness, that you might not even notice it’s there. It feels like just being awake. Like thinking. Like your mind doing what minds do.

But here’s what’s interesting: that narrator isn’t always on. The constant commentary, the mental chatter, the stream of self-referential thoughts—these emerge from a specific neural network in your brain. A network that has a name: the Default Mode Network, or DMN.

And even more interesting: you can quiet it down. Through mindfulness practice, you can literally reduce the activity of this network. You can experience periods where the inner narrator pauses. Where thought isn’t constantly referencing you, your past, your future, your problems.

When that happens, something remarkable occurs. The mental noise quiets. Your mind becomes clear. You experience presence. Peace. A sense of spacious awareness that’s rarely available to you in ordinary consciousness.

The research on this is conclusive. The mechanism is understood. And this capacity is available to you right now.

Part 1: The Default Mode Network—Understanding Your Brain’s Automatic Pilot

Before we can talk about quieting the DMN, you need to understand what it actually is and what it’s doing.

Your brain has multiple networks. The task-positive network activates when you’re focused on external tasks—working, conversing, problem-solving. The salience network helps you detect what’s important in your environment. And then there’s the Default Mode Network—a collection of brain regions that activate when you’re not focused on external tasks.

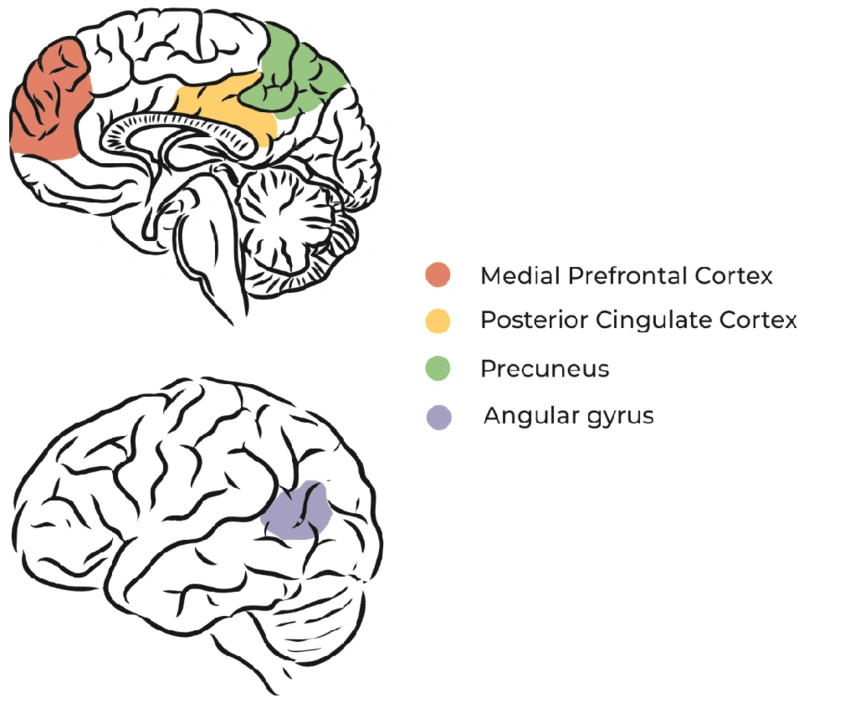

The DMN consists of several interconnected regions:

- The medial prefrontal cortex (involved in self-referential thinking)

- The posterior cingulate cortex (involved in memory retrieval and self-reflection)

- The precuneus (involved in self-awareness and autobiographical memory)

- The angular gyrus (involved in social cognition and theory of mind)

- The hippocampus (involved in memory)

When you’re not actively focused on something, these regions activate together. And when they do, your mind does what feels like its default activity: it thinks about you. Your life. Your problems. Your identity. Your past. Your future.

The DMN was first discovered in the early 2000s by neuroscientist Marcus Raichle, who noticed something puzzling. When participants were lying in an fMRI scanner doing nothing—just resting without a specific task—certain brain regions actually became more active than during focused tasks.

This seemed counterintuitive. Shouldn’t the brain be less active when at rest?

But Raichle realized these regions were coordinating to create what he called the “default mode.” When you’re not engaged in external focus, your brain defaults to internal activity. To thinking about yourself. To memory retrieval and autobiographical narration.

This is adaptive, actually. You need to reflect on your experiences. To plan for the future. To think about your identity and your place in the world. The DMN enables these crucial functions.

But here’s where the problem emerges in modern life.

Part 2: The Tyranny of Self-Reference—How DMN Activity Shapes Your Behavior and Mood

The DMN is always evaluating you. Always comparing. Always narrating your life story. In small doses, this self-referential thinking is fine. But when the DMN is chronically overactive—which it is for most modern humans—it becomes a source of suffering.

When your DMN is highly active, your mind is essentially doing four things simultaneously:

Self-referential thinking: Your mind is constantly relating external information back to yourself. You see someone successful and your mind thinks, “I’m not like that.” You experience a setback and your mind creates a narrative: “I always fail at things like this.” Everything is filtered through the question: “What does this mean about me?”

Rumination: Your mind is replaying past events, getting stuck in loops of “Should I have done that differently?” or “Why did they say that?” Neuroscientist Susan David calls this “rumination loops”—where your DMN gets stuck, recycling the same thoughts without reaching resolution.

Anticipatory worry: Your mind is simulating future scenarios, most of them negative. “What if that happens?” “What if they don’t like me?” “What if I fail?” Your DMN is constantly running threat simulations about a future that hasn’t occurred.

Self-judgment: Your mind is evaluating your own thoughts and experiences. “I shouldn’t feel this way.” “I’m not good enough.” “This anxiety means something is wrong with me.” You’re experiencing an experience, and simultaneously judging yourself for having it.

Together, these four functions create what feels like a constant low-level suffering. Not acute pain, but a background anxiety. A sense that something is wrong. A disconnection from what’s actually happening right now.

And here’s what’s crucial: this entire internal narrative feels like truth. It feels like reality. You believe the story your DMN is telling. You think these self-referential thoughts are accurate descriptions of who you are.

But they’re not. They’re just thoughts. Neural patterns. Constructions of your DMN. They have no more fundamental truth than the plot of a movie you’re watching.

This is where most people get stuck. They believe their thoughts are accurate reports of reality. They believe their ruminations about the past are important. They believe their worry about the future is necessary.

And so they suffer continuously, imprisoned in the DMN’s narrative loops.

Part 3: The Modern Crisis—Why the DMN Is Overactive Like Never Before

Your Default Mode Network evolved over thousands of years in a relatively stable environment. Your ancestors had time to think about their identity, to plan for the future, to reflect on past experiences. The DMN served an important function.

But your modern life has completely changed. Your environment is nothing like the environment the DMN was designed for.

Consider what’s happening right now. Your phone is probably nearby. You have dozens of browser tabs open in your mind (literal tabs in your browser if you’re sitting at a computer). You have notifications arriving constantly. Your attention is being fragmented across multiple streams of information simultaneously.

And what has this done? It has made the DMN hyperactive.

When your attention is fragmented, your brain can’t settle into focused external awareness. So your DMN activates more frequently. You mind-wander more. You ruminate more. You engage in more self-referential thinking.

Research shows that the average person’s mind wanders about 30–47% of the time during daily activities. Thirty to forty-seven percent of your conscious life is spent in DMN-dominated activity—thinking about yourself, worrying about the future, ruminating about the past.

And here’s what’s particularly revealing: studies show that mind-wandering makes you unhappy. When Harvard researchers used an app to ping participants randomly and ask what they were thinking, they found that when people’s minds were wandering, they reported lower happiness levels than when they were focused on the present moment.

The DMN isn’t your friend in this context. It’s a suffering-generation machine.

Add to this the constant news cycle, social media comparisons, financial uncertainty, and global anxiety, and what you get is a Default Mode Network that’s running overtime. It’s producing rumination. Worry. Self-doubt. Anxiety. A pervasive sense that something is wrong.

And because the DMN is so active, you’ve become habituated to this state. You think it’s normal. You think this is just how consciousness works. You don’t realize that most of your suffering is being generated by an overactive neural network that you could actually learn to quiet.

Part 4: The Mindfulness Solution—How Meditation Deactivates the Default Mode Network

Here’s where everything changes.

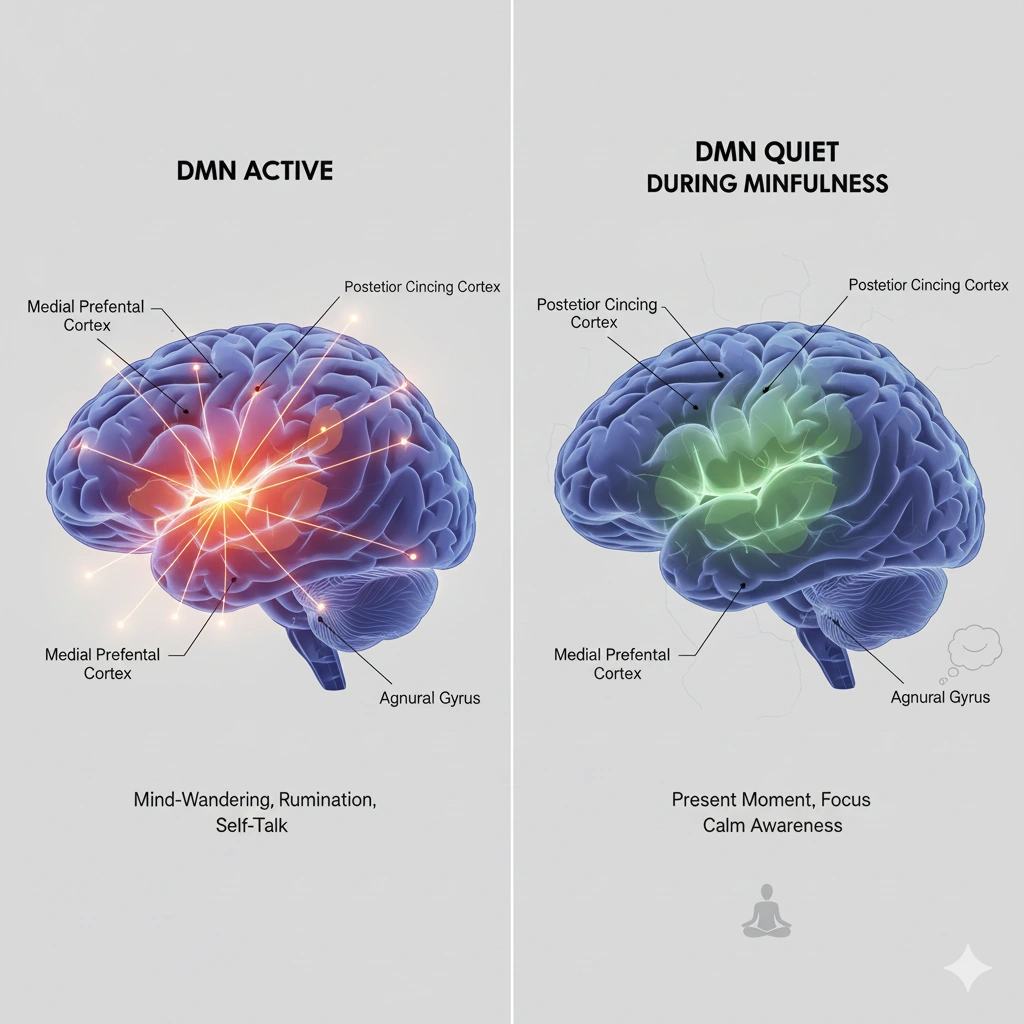

When you practice mindfulness meditation, something specific happens to your Default Mode Network. It quiets down.

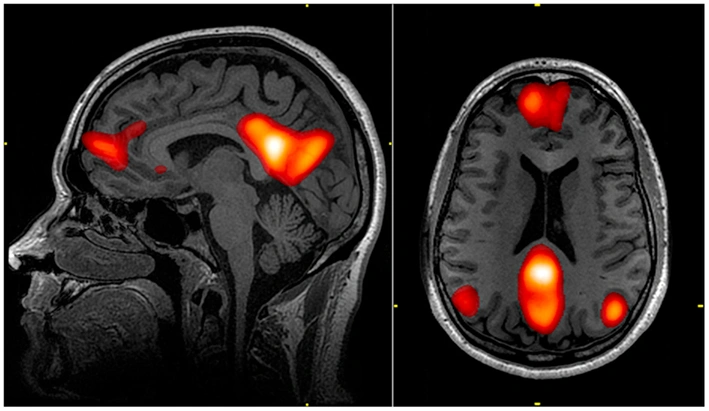

This isn’t metaphorical. It’s measurable. fMRI studies show that when experienced meditators enter meditative states, the regions of the DMN show significantly reduced activity compared to non-meditators. The neural regions that were busily generating self-referential narratives become less active.

But what’s replacing that activity? What is your brain doing if it’s not running the default mode?

This is the fascinating part. When the DMN quiets, activity increases in what’s called the “salience network”—the brain regions associated with present-moment awareness and attention to what’s actually happening right now.

So mindfulness isn’t creating a void. It’s shifting your brain from one mode to another. From internal self-referential narration to present-moment awareness.

When you sit down to meditate and bring attention to your breath, you’re activating the task-positive network (the regions involved in focused attention) and simultaneously reducing DMN activity. Your self-referential narration quiets. Your mind-wandering decreases. Your rumination stops.

What’s remarkable is that this doesn’t feel like forcing yourself to stop thinking. It feels like your mind naturally settling. Like water becoming still. The constant mental chatter simply quiets because your brain isn’t being asked to engage in self-referential thinking anymore.

The mechanism is elegant: attention is a limited resource. When you direct it toward your breath, toward bodily sensation, toward the present moment, there’s less attention available for DMN activity. The DMN requires your attention to run its narratives. Redirect that attention, and the DMN becomes less active.

With repeated practice, your brain becomes increasingly efficient at this shift. The DMN quiets more readily. You experience longer periods of presence. And over time, your baseline DMN activity decreases even when you’re not meditating.

This is why experienced meditators report that their mind-wandering decreases in daily life. Why they’re less caught in rumination. Why they seem more present. Their DMN has been trained to be less reactive.

Part 5: The Research—What Science Shows About Mindfulness and the DMN

The connection between mindfulness and DMN deactivation has become one of the most studied phenomena in contemplative neuroscience. The evidence is robust and consistent.

The Foundational Studies: DMN Deactivation

In 2011, researchers at the University of Montreal led by Judson Brewer conducted a landmark study examining the relationship between meditation experience and DMN activity. They scanned experienced meditators while they meditated and during rest periods.

The finding was striking: during meditation, the DMN showed significantly reduced connectivity. The regions that normally communicate with each other to generate self-referential narratives were less synchronized. And remarkably, the amount of DMN deactivation correlated with meditation experience. The more hours someone had meditated, the more their DMN quieted during meditation.

But even more significantly: experienced meditators showed reduced DMN activity even during rest periods—when they weren’t actively meditating. Their baseline DMN activity had actually changed. Their brains had been trained to be less self-referential.

In 2015, Brewer published follow-up research examining a specific aspect of DMN activity: mind-wandering. He used fMRI to measure how much people’s minds wandered during different activities. Then he compared this to their meditation experience.

The finding: people with regular meditation practice showed significantly less mind-wandering during daily activities compared to non-meditators. Their DMN wasn’t automatically activating every time they weren’t focused on a specific task.

Long-Term Changes: The Plasticity Evidence

What’s crucial about these studies is that they show mindfulness doesn’t just suppress the DMN during meditation. It actually changes it. It rewires it.

A 2014 study published in Cerebral Cortex examined structural brain changes in long-term meditators. Researchers found:

- Reduced gray matter volume in the medial prefrontal cortex (a key DMN region)

- Reduced connectivity between DMN regions

- More efficient attention networks (suggesting that meditators’ brains had become more capable of shifting away from the DMN)

This is remarkable because it shows that meditation doesn’t just create temporary changes. It actually alters brain structure. Your brain is being physically reorganized to be less DMN-dominant.

The Rumination Reduction Studies

Beyond structural changes, researchers have examined how mindfulness affects the specific DMN functions that generate suffering. Multiple studies show that mindfulness practice reduces rumination—the tendency to get stuck in repetitive thoughts about the past.

A 2015 meta-analysis examining 15 studies on mindfulness and rumination found that mindfulness-based interventions consistently reduced rumination by approximately 20–30%. The effect was independent of depression or anxiety—it was specifically about reducing the tendency of the DMN to get caught in repetitive thought loops.

The Real-World Impact: Daily Life Studies

Beyond laboratory measurements, researchers have examined how mindfulness affects DMN-related problems in daily life.

A 2013 study in Consciousness and Cognition had participants wear devices that randomly prompted them to report what they were thinking and how happy they were. Meditators showed:

- Less frequent mind-wandering (consistent with reduced DMN activity)

- Greater ability to notice when their minds had wandered

- Faster ability to redirect attention when they noticed mind-wandering

- Higher reported happiness levels

Importantly, the study found that meditators weren’t necessarily thinking different thoughts. They were just less identified with their thoughts. They could notice mind-wandering without getting caught in it.

Timeline: How Quickly Does the DMN Change?

One of the most encouraging findings: DMN changes happen relatively quickly. While some structural brain changes take months or years, functional changes in DMN activity can be detected within weeks.

A 2016 study found that even 8 weeks of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) produced measurable reductions in DMN activity and connectivity. Participants showed:

- Reduced mind-wandering during daily activities

- Reduced rumination

- Improved attention span

- Greater ability to stay present with experience

The brain’s plasticity means that even relatively short-term practice can begin shifting your default mode from chronic DMN activation to more balanced activation.

Part 6: The Hidden Obstacles—Why Most People Struggle to Quiet the DMN

The research is clear. Quieting the DMN is possible. It produces measurable benefits. And yet most people who try mindfulness struggle with it or quit before they experience real DMN-related changes.

Why?

The first challenge is that the DMN feels like you. When your mind is dominated by self-referential thinking, it feels like that’s just who you are. “I’m an anxious person.” “I’m a worrier.” “I’m someone who overthinks.” You’ve identified with the DMN’s narratives so completely that quieting it feels threatening. Like you’re losing yourself.

The second challenge is that the DMN is incredibly persistent. Your brain has been practicing DMN dominance for decades. Redirecting attention away from the DMN can feel like swimming upstream. Your mind keeps returning to self-referential thoughts even when you’re trying to focus on your breath.

The third challenge is the initial discomfort. When you first start meditating, sitting with your mind and truly noticing the DMN’s activity can be overwhelming. You might notice for the first time how much your mind actually wanders. How much rumination and self-judgment is happening. How much anxiety is being generated. This can feel like meditation is making things worse, so you quit.

The fourth challenge is the subtlety of the benefits. DMN quieting doesn’t produce dramatic symptoms like pain reduction or cortisol drops. The benefit is subtle. You’re slightly less anxious. Slightly more present. Slightly less caught in rumination. For someone expecting dramatic results, this subtlety can feel like the practice isn’t working.

The fifth challenge is consistency. The research showing significant DMN changes involves consistent daily practice. Many people meditate sporadically and expect significant changes. When the changes are less pronounced, they assume mindfulness doesn’t work for them.

The sixth challenge is the difficulty of direct measurement. You can’t easily measure your own DMN activity. You can’t see your rumination decreasing or your mind-wandering reducing. So you’re practicing on trust and subtle internal shifts rather than clear objective data.

The seventh challenge is the “rubber band” effect. Even as your practice quiets the DMN, if your daily life remains chaotic, fragmented, and stress-filled, the DMN reactivates. Your mind returns to its default patterns. You need your life circumstances to support the quieting you’re cultivating through practice.

Part 7: The Simple Practice—A 10–15 Minute Daily Protocol for DMN Quieting

Understanding the neuroscience of DMN deactivation is interesting. But what matters is practice. Here’s a simple, evidence-based protocol that research shows effectively quiets the DMN. You need just 10–15 minutes daily.

The Setup (2 minutes)

Find a quiet place where you won’t be interrupted. Sit comfortably—either in a chair or cross-legged on a cushion. The key is upright posture without tension. Hands resting on your legs. Eyes either closed or gazing softly downward.

Set a timer for 10–15 minutes. This eliminates the “how long have I been sitting?” question that would activate your DMN (self-referential thinking about time).

The Foundation: Breath Awareness (5 minutes)

Bring your attention to your breath. Not to control it—just to notice it. Where do you feel it most clearly? The coolness of air entering your nostrils? The expansion of your chest or belly? The sensation of exhales?

Choose one location and rest your attention there. When you notice your mind has wandered—and it will—gently redirect attention back to your breath. No judgment. No resistance. Just a gentle returning.

This process of noticing mind-wandering and redirecting attention is the core practice. Every time you do this, you’re training your brain to shift away from DMN-dominance. You’re strengthening your capacity to notice when your mind has gone into self-referential thinking and to choose to redirect.

The Deepening: Body Scan (3–5 minutes)

After 5 minutes of breath awareness, expand your attention. Notice your entire body. The sensations where your body meets the seat. The feeling of your hands. The temperature of the air on your skin.

You’re not trying to feel anything special. You’re just gathering sensory information from your body. This present-moment sensory awareness directly contradicts DMN activity. The DMN wants to narrate; body sensation anchors you in what’s actually happening now.

The Release: Open Awareness (2–3 minutes)

In the final minutes, release the focus on breath or body. Allow your attention to be open and spacious. Thoughts might still arise, but you’re not following them. You’re just aware. Present. Like sky noticing clouds passing through. You’re not trying to stop thinking. You’re just not engaging with the thoughts that arise.

This is where you directly experience reduced DMN activity. Your mind isn’t narrating. Your inner narrator has quieted. You’re experiencing presence without the constant commentary.

The Key: Consistency, Not Duration

The research shows that 10–15 minutes daily produces measurable DMN changes. What matters is consistency. Daily practice is far more effective than occasional longer sessions.

Your brain learns through repetition. Every day you practice, you’re sending a signal to your nervous system: “This present-moment awareness is important. Shift away from self-referential thinking.” Over weeks and months, your brain adapts. The DMN becomes less reactive. Your baseline consciousness shifts toward more presence and less rumination.

Part 8: Comprehensive Solutions—Making DMN Quieting Stick

A 10-15 minute daily practice is powerful. But integrating DMN-quieting into your entire life requires additional strategies.

Anchor Your Practice: Pick a Specific Time

Don’t meditate when you “have time.” You’ll never have time. Instead, anchor your practice to an existing habit. Meditate immediately after you wake up. After your morning coffee. After dinner. Before bed. By making it non-negotiable and consistent, you remove decision-making from the process. Your brain learns: “This is when we meditate.”

Measure What You Can: Rumination and Mind-Wandering

You can’t measure your DMN activity without an fMRI. But you can track the behaviors that indicate DMN activity. Each evening, rate:

- How much time did you spend ruminating today? (0–10 scale)

- How often did you notice your mind wandering during important activities? (0–10 scale)

- How much did self-judgment dominate your thinking today? (0–10 scale)

After 4–8 weeks, you should see reductions in these metrics. This data is profoundly motivating.

Extend the Practice: Informal Mindfulness

Beyond your formal 15-minute practice, bring mindfulness to daily activities. During meals, really taste your food (present-moment awareness reduces DMN). During conversations, genuinely listen rather than planning your response (listening requires task-positive network activation, quieting DMN). During walks, actually notice your surroundings rather than ruminating (sensory awareness reduces DMN).

Each moment of present-moment awareness trains your brain away from DMN-dominance.

Address Digital Fragmentation

The modern environment constantly fragments your attention, which drives DMN activation. Take deliberate steps to reduce this:

- Disable non-essential notifications

- Use website blockers to prevent constant checking

- Establish “no phone” times

- Reduce the number of tabs you keep open

- Practice single-tasking rather than multitasking

These changes reduce the stimulation that triggers excessive DMN activity.

Create External Silence

Silence—real silence—is increasingly rare. Your DMN thrives in silence because without external sensory input, your brain defaults to internal narration. But silence can also help quiet the DMN if you’re practicing mindfulness.

Regularly spend time in genuine quiet. No phone. No music. No podcasts. Just you and the present moment. Your DMN might be initially uncomfortable with this, but with practice, you’ll find that the silence creates space for the present-moment awareness that quiets the DMN.

Work With Intention, Not Willpower

Here’s a crucial mindset shift: you’re not trying to “stop thinking” or “suppress the DMN.” You’re simply practicing present-moment awareness. The DMN quieting happens naturally as a result. Trying to force quiet creates tension, which actually activates the DMN.

Instead, approach your practice with gentle curiosity: “What happens when I simply pay attention to this breath? What’s it like to be here, now?” This gentle intention guides your brain toward DMN quieting without the resistance that willpower creates.

Part 9: The Liberation—What Quieting the DMN Actually Restores

When your Default Mode Network quiets, something shifts that goes deeper than just “having fewer anxious thoughts.”

Your constant internal evaluation stops. You’re no longer comparing yourself to others, judging yourself against standards, rehearsing past mistakes. That exhausting self-monitoring quiets. You can be present without the internal commentary.

Your presence becomes genuine. You’re actually here with the people you love. Actually hearing them. Actually connecting. Not half-listening while your DMN narrates judgments or plans. The quality of your life improves immediately through simple presence.

Your creativity awakens. The DMN isn’t just a suffering-generation machine. It’s also the default thinking pattern—the habitual neural pathway. When it quiets, different neural patterns become possible. Novel connections emerge. Insight becomes accessible. You think more creatively because your brain isn’t locked into its habitual DMN pathways.

Your anxiety decreases. Anticipatory worry—the DMN simulating future threats—diminishes. Not because you’re denying real concerns, but because your brain isn’t constantly rehearsing what might go wrong. The noise of rumination and worry quiets, leaving genuine clarity about what actually needs attention.

Your relationship to your thoughts transforms. You notice thoughts arising, but you’re less identified with them. A thought about your inadequacy arises, and instead of “I’m inadequate,” you notice “A thought about inadequacy just appeared.” This distinction—between being your thoughts and observing your thoughts—is profound. It frees you from the tyranny of believing every narrative your mind generates.

And perhaps most profoundly: you gain access to presence. Not a special state, but the ordinary clarity of being here now. The direct experience of life as it’s actually happening, without the DMN’s interpretation layered on top.

That’s what quieting the Default Mode Network restores. Not escape from thinking, but freedom from being imprisoned in habitual thinking patterns. Not blankness, but clarity. Not numbness, but genuine presence.

The Invitation

Right now, your Default Mode Network is probably active. Your mind is doing what it does—narrating, comparing, judging, planning, worrying. It feels like you. It feels like reality.

But it’s not. It’s one mode among many. And through a simple 10–15 minute daily practice, you can train your brain to quiet this mode. To shift toward presence. To experience the peace that exists beneath the constant mental noise.

The research is clear. The mechanism is understood. The benefits are significant and relatively quick.

The question is: are you willing to sit quietly for 15 minutes each day and discover what your mind actually sounds like when the Default Mode Network quiets?

References & Further Reading

- Brewer, J. A., Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y. Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20254-20259.

- Brewer, J. A., Garrison, K. A., & Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. (2013). What about the “self” is processed in the posterior cingulate cortex? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 647.

- Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain’s default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433-447.

- Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932.

- Corbetta, M., & Shulman, G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(3), 215-229.

- Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213-225.

- Garrison, K. A., Santoyo, J. F., Davis, J. H., Thornhill, T. A., Kerr, C. E., & Brewer, J. A. (2013). Effortless awareness: using real time fMRI neurofeedback to investigate correlates of posterior cingulate cortex activity in meditators’ self-report. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 440.

- Hasenkamp, W., Wilson-Mendenhall, C. D., Duncan, E., & Immordino-Yang, M. H. (2012). Mind wandering and attention during focused task performance: an fMRI study. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e36760.

- Moran, T. P. (2016). Anxiety and working memory capacity: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 142(8), 831-864.

- Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Wasserman, R. H., Gray, J. R., Greve, D. N., Treadway, M. T., … & Fischl, B. (2005). Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. NeuroReport, 16(17), 1893-1897.

Goleman, D., & Davidson, R. J. (2017). Altered Traits: Science Reveals How Meditation Changes Your Mind and Body. Bantam.